Exploring Information Controls by Iran on Instagram

Team Members

Mahsa Alimardani, Cecilia Andersson, Erik Borra, Stefanie Duguay in consultation with Frederic Jacobs.Key Words

Iran, Instagram,Social Media EcologiesIntroduction

This study was inspired by research done my Mahsa Alimardani and Frederic Jacobs for Global Voices Advocacy.Irans Intelligent Filtering of Instagram

Centralization of Iranian cyberspace came to fruition during and after the 2009 protest movement against the fraudulent presidential elections. The unrest that ensued in 2009, with the aid of communication technology devices, such as Facebook, active blogs, and online TV streams of opposition candidates Mehdi Karroubi and Mir Hossein Mousavi, resulted in the later shut down or filtering of many websites, including Facebook and Twitter. From this point onwards cyberspace was considered a sphere of threat to national security in need of state control. As such, this online censorship is an indicator of a government strategy to restrain society. Researchers see this online restraint as a tool in reducing the availability of information, and criticism against the government, and an obstruction in the development of online communities' development (Faris and Villeneuve 2008).

New Efficiency in Internet Controls in Iran

The study of Irans Internet reveal a discourse of increasing control, and centralization of Internet policy. The government has indicated through a number of statements and projects their desire to build a stronger national internet infrastructure, and implement sophisticated technology in both the practices of surveillance and censorship of the Iranian Internet.

It is not certain when the 'intelligent' filtering program started targeting Instagram pages, but we know that this started as early as October 2014, when the first reported page belonging to the Rich Kids of Tehran were blocked (AFP 2014). Statements in March by the Minister of ICT Mahmoud Vaezi indicate that this is a multi-phased program by the Ministry to make sure Iranians can still access appropriate content on the platform. Vaezi has declared that his Ministrys intention is the following: Our policy is that we will not restrict the activities of any mobile social media, and when we do announce it, it will be when we find an alternative for this network inside the country (Shargh 2015). As stated before, there is an increasing awareness of the ineffectiveness in blocking these platforms, and as such there is a push towards intelligent filtering as a new method of Internet control.

The concept of 'intelligent' filtering first arose during Mahmoud Ahmadinejads Presidency. In late 2012 a Facebook page was created for the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, leading many to speculate that Iranian authorities were rethinking policies regarding the filtering of Facebook and Twitter.

Instagram has so far been the first and only application of 'intelligent' filtering on social media. In December of 2014, Vaezi declared that the 'intelligent' filtering program was in its pilot phase, blocking immoral and criminal content (Shargh 2014). Irans cyber police, Gerdab, however did clarify that the 'intelligent' filtering program is unable to work on websites that use a SSL protocol, including Instagrams browser version (SNN 2015).

What remains to be said however, is that the correlation between the Ministers statements regarding Smart Filtering, and the technical implementation of the filtering process remain to be vague. With the May 2015 study that has inspired this current research, it became apparent that intelligent filtering, or per page censorship on Instagram content was no longer possible once https was implemented on the mobile application. A few options are still open to them such as filtering on a per image basis (instead of a per user basis) since images are sent over HTTP from Instagrams content delivery network. This would prevent an offensive image from being displayed within a users profile page while the number of followers, biography, likes and comments of pictures would still be able to load, as these are sent over HTTPS. Because of these platform specifications, and recent reports that intelligent filtering is now occurring for certain images, the first part of this study endeavors to understand why Iranians have had difficulty uploading certain images on Instagram (ICHRI 2015). For example, users in Iran were unable to upload random images that were seemingly innocuous photos without political motivations

This has led to some suspicions by Iranian Internet users and researchers that this is a conscious effort at censoring images belonging to activists (ICHRI 2015).

For this reason, this study endeavors to ask, does intelligent filtering now continue on a per image basis?

Additionally, to further explore the question of controls inside of Iran, this study endeavors to understand the monitoring and shaping Iranian authorities might implement in the wake of the IRGC Spider program.

Research Question

How is the Iranian government censoring and shaping the flow of information online?

Part A

-

Is the Iranian government targeting images to censor or is Instagram crossing with censored IP ranges for Facebook?

Part B

-

What does the network ecology of Iranian activists, government opposition, and pro-regime Instagram accounts look like?

-

Are there differences among these networks that help us to identify suspicious accounts?

Methodology

Using expert knowledge of the Iranian activists and politicians, we created three categories of actors: activists, opposition leaders, and members of the current government and elite.

Part A: Studying Instagram Censorship

Gather all IP address assigned to Facebook, as follows: <code>/usr/bin/whois -h whois.radb.net '!gAS32934' | tr ' ' '\n' | sort -n -k1,1 -k2,2 -k3,3 -k4,4</code>

For this we sorted list of IP addresses assigned to Facebook, get the associated hostname(s) through the following command: <code>host IP_ADDRESS</code>.

The hostnames returned will indicate for which service Facebook uses the IP address and for which location it serves results. E.g. instagram-p3-shv-01-fra3.fbcdn.net serves results for instagram from France. Geo-IP lookups confirmed this. For a total list of 23712 IP addresses, 5431 hostnames were found.

Filtering this list for hostnames which contain 'instagram' resulted in 100 IP addresses with associated hostnames. Here is the list of location frequencies for hosts containing 'instagram': ams (7), arn (2), ash (3), atl (2), bru (2), cai (4), cdg ( 6 ), dfw (2), fra (11), frc (4), gru (2), hkg ( 6 ), iad (3), kul (2), lax (2), lga (2), lhr (2), lla (10), mad (2), mia (2), mrs (2), mxp (2), nrt (2), ord (2), prn (2), sea (2), sin (2), sjc (2), syd (2), tpe (2), vie (2), yyz (2)

To test whether the hosts are accessible, telnet connections were made to each IP and host on ports 80 (HTTP) and 443 (HTTPS). This was done both from the Netherlands, as well as from a Virtual private Server (VPS) in Iran. The results were then compared.

Part B: Instagram Networks

-

Build seed samples of Instagram accounts (activists, government opposition, and pro-regime accounts)

-

Enter lists of accounts into the DMI Instagram Network Collection Tool (https://tools.digitalmethods.net/beta/instagramNetwork/) to gather follower networks

-

Open the network graphs and analyse trends in Gephi

-

Take the usersnames of follower networks from the tools CSV output and enter these in the DMI Instagram User Info Scraper: https://tools.digitalmethods.net/beta/instagramUserInfo/

-

Examine and compare user info from different follower networks.

Findings

Part A.

- Results are same for domain and IP (no overblocking?)

- Comparing IR and NL: 64% of HTTPS connections fail in IR, but not in NL, 6% of HTTP connections fail in IR, but not in NL

- Thus:

-

images served over HTTPS are (generally) being blocked in Iran

-

no content based blocks but (temporary) inaccessibility based on the IP addresses used by the CDN

Speculation: sporadic inaccessibility of Instagram images is collateral damage from Facebook block (accidental overblocking?)

-

-

Speculation: sporadic inaccessibility of Instagram images is collateral damage from Facebook block (accidental overblocking?)

Part B.

Activist Network Cross Platform Analysis

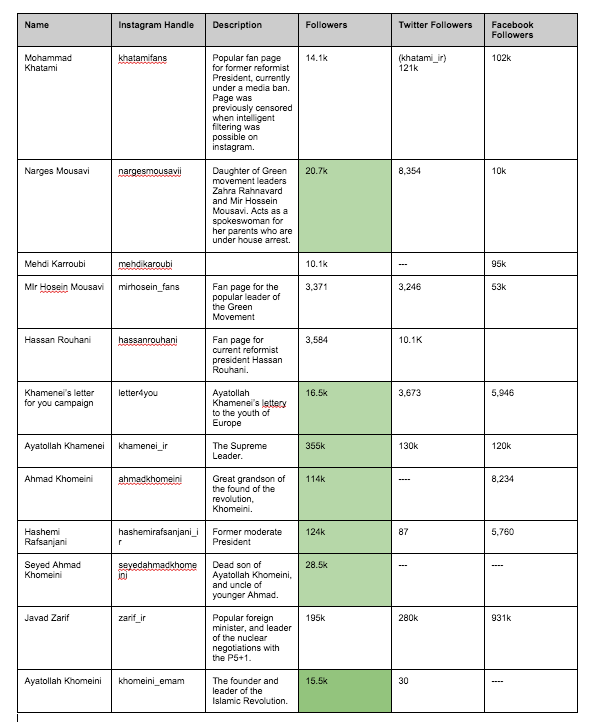

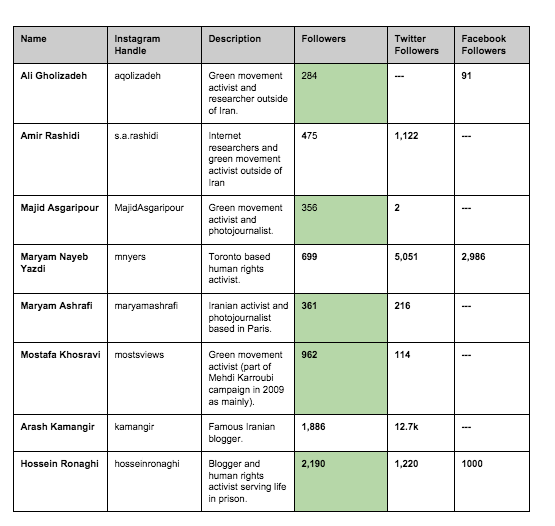

Table 1. Seed actor information, and cross-platform comparison.

The social media presence of a few of these actors is solely based on their Instagram presence, such as the jailed activist Hossein Ronaghi. Other activists whose background is based in photography, such as Mostafa Khosravi and Ali Gholizadeh.

Opposition and Pro-Government Network

In examining the networks that the followers of prominent politicians, who are both part of Irans hardliners, reformists, current government, and opposition illustrated an interesting network of interconnections for us.

Table 2. Seed actor information, and cross-platform comparison.

Amongst these political figures, it is evident that certain personalities are present in social media predominantly through their instagram accounts. Narges Mousavi, who is in many ways the defacto spokesperson for her parents, the Green Movement leaders currently under house arrest, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Zahra Rahnavard, has about 20, 000 followers for her photos. Khameneis Letter4You campaign seems to be dominant mainly on Instagram -although studies regarding bots tweeting the hashtag for this campaign might be a reason why there are less Twitter followers. Surprisingly, the Supreme Leaders Instagram page dominates in the other major platforms he is present on. His account predominately features images of him from the past and present, with other significant members of the clergy and elite, or featuring him in many of his public appearances around Iran, or praying. The account for Ahmad Khomeini is a platform much talked about and discussed, by reformists and hardliners in Iran, as he is the offspring of one of the holiest figures in the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Khomeini, the founder and leader of the Islamic Revolution. The popularity, and celebrity associated with his Instagram account that illustrates the behind-closed doors of some of the countrys elite, is touted by many to be transforming the culture of the Iran in one filled with many western mores of celebrity, and exposure (Economist 2014). Other significant accounts are for the long deceased Khomeini, and his son Ahmad, who maintain large followings on memorial Instagram accounts.

The popularity of Instagram as such seems to indicate an integration into western modes of celebrity and exposure. This in turn might signify the general shift Iran is experiencing under the current moderate administration of Hassan Rouhani, and the push towards reconciliation with the United States and the Western world -more integration into the global world.

Network Analysis

Further analysis of the networks that followers of these accounts form elaborates a little more on the political tendencies, and influence of these actors inside Iran through the perspective of Iranian Instagram usage. It must be noted that we could not verify whether these accounts were located inside or outside of Iran, but the majority were using Iranian usernames, and posting in the Persian language.

Figure 3. Network of followers belonging to opposition and pro-government actors.

The clusters of followers are clearly divided, with different communities for the different politician nodes under examination. What is clearly evident here, is that the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khameneis campaign letter4you maintains the most separated community of followers at the bottom of the graph. This follows the research already done on the letter4you Twitter account, that is being populated by interactions and followers by bots, tweeting the accounts associated hashtag #letter4you (Alimardani 2015). The interconnectedness of followers between the Supreme Leader Khamenei and the current Foreign Minister Javad Zarif is also notable. In fact Khamenei, Zarif, the former moderate President Rafsanjani, and the young great-grandson of the founder of the revolution Ahmad Khomeini all cluster closely on the left of this network. What is surprising however, is the close relationship between the followers of the memorial accounts of the founder of the revolution Khomeini, and his son Seyed Ahmad, with reformist and opposition elements such as khatamifans (a previously censored account when intelligent filtering was underway), and members of the Green Movement who are under house arrest, such as mirhosein_fans and mehdikaroubi.

Figure 4. Network of Activist Followers.

The connection of actors explains the relationships and work of different types of Iranian activists. You can clearly see the actors with the most followers. Hossein Ronaghi, well known for his blogging and subsequent incarceration has a strong community of followers in common with another notable blogger, Arash Kamangir, that lives in exile in Canada. Similarily, the exiled Green Movement activists mostsviews and s.a.rashidi are both strongly connected at the center of the network, alongside another lesser followed Green Movement activist now living outside of Iran (aqolizadeh). The activist photojournalists Maryam Ashrafi and Majid Asgarisadeh also have the strongest connection of followers, probably related to their similar professions. Maryam Nayeb Yazdi, whose main profession is activism (unlike the others who have descriptions as researchers, bloggers, prisoners and photographers) is at the bottom of the network, mainly sharing followers with those activists living in exile.

Figure 5. All Networks Combined (Connections between Activists, Iranian Opposition Figures, and the members of the government and elite).

The overall network initially just looks like the activist network loosely connected with the network of government and pro-regime elites, and opposition figures. However, we can see some loose, and often random associations between the followers of activists and government affiliated members. For example, kamangir sares followers with individuals such as Rafsanjani, and Ahmad Khomeini.

Network User Info Analysis

Using the DMI Instagram User Info scraper, we collected information about users in the activist and pro-regime networks, including how many posts, followers, and users they are following. Although some queries did not return data, we were able to obtain user information for 7, 184 activist follower accounts and 7,997 pro-regime follower accounts. Of the activist accounts, 4,290 (about 60%) were public and of the pro-regime accounts, 5,230 (about 65%) were public.

We were only able to retrieve detailed user information for public accounts. From analysis of this information, we found that only 9% of activists followers public accounts had 0 posts while 26% of pro-regime followers public accounts had 0 posts. Therefore, many pro-regime followers have empty Instagram accounts.

To further examine the account activity in each network, we looked at the distribution of the number of posts, followers, and users followed. When plotting the distribution of posts in the activist network and comparing this with the distribution of posts in the pro-regime network, we found that not only did the pro-regime network have many more accounts with 0 posts, pro-regime accounts that did post photos were much less likely to post a lot of content. There were 233 pro-regime public accounts that had between 100-200 posts while there were 542 activist accounts with between 100-200 posts. Figure 7 depicts this comparison between the networks, showing that the pro-regime posting activity is much less than the activist network.

Similarly, activists followers were much more likely to have at least some followers. There were 63 pro-regime public accounts with 0 followers and only 4 activist public accounts with 0 followers. There were 3,377 (65%) pro-regime accounts that had between 0-100 followers in contrast with only 919 (21%) activist accounts that had between 0-100 followers. Figure 8 illustrates this difference in followers. This makes sense, since users would not be motivated to follow the large number of pro-regime accounts that do not have many posts.

As shown in Figure 9 pro-regime accounts were also much less likely to follow other users than activist accounts. Only 645 (15%) activist accounts were following fewer than 100 users with just slightly more activist accounts (552) following between 100-200 accounts. In contrast, 2,211 (42%) pro-regime accounts were following fewer than 100 users with 13 pro-regime accounts not following any users.

When using the DMI Triangulation tool to compare the usernames in each network, we found there were 1,106 users that appeared both in the activist and the pro-regime network. Given the low activity of pro-regime accounts and the numerous pro-regime accounts that are empty, it is likely that many of the accounts shared between the networks also have these suspicious characteristics. This highlights these users for further investigation to determine whether these might be accounts created to surveil activist Instagram networks.Hack instagram

Conclusion

- Certain Iranian censorship is potentially collateral damage from the block put in place on Facebook.

-

Instagram is increasingly reshaping social media use in Iran. Influential Iranians have more followings on Instagram than on Twitter or Facebook. Followers are shared by disparate groups.

-

There were clear differences between users in the activist follower network and the pro-regime follower network, with pro-regime accounts being much less active on Instagram.

Further Research

- Conduct interviews with Instagram users to ask if they have noticed any suspicious users in their network

- Work with Facebook's troll investigation team.

Literature

Alimardani, M. (2015). Khamenei's #Letter4U Bots Still Active Four Months After Its Launch. Globalvoicesonline.org. Alimardani, M and Jacobs, F. (2015) Iran is Using Intelligent Censorship on Instagram.Advocacy.globalvoicesonline.org. Chen, C., Wu, K., Srinivasan, V., & Zhang, X. (2013). Battling the Internet water army: Detection of hidden paid posters. 2013 IEEE/ACM International Conference On Advances In Social Networks Analysis & Mining (ASONAM 2013) , 116. Cresci, S, Di Pietro, R., Petrocchi,M., Spognardi, A., Tesconi, M. (2014). A Fake Follower Story:improving fake accounts detection on Twitter. IIT TR-03/2014 Technical report. Istituto di Informatica e Telematica Easley, D., & Kleinberg, J. (2010). Networks, crowds, and markets : reasoning about a highly connected world. New York : Cambridge University Press. Faris, R. and Villeneuve , N (2008) . Measuring Global Internet Filtering. In Deibert, R. (red.) (2008). Access denied: the practice and policy of global Internet filtering Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Iran blocks Instagram account of Ârich kids showing off wealth in Tehran. (2014, October 9). Agence France-Presse. Retrievad from http://www.theguardian.com/ OpenNet Initiative (2013). After the Green Movement: Internet Controls in Iran, 2009-2012.Look for how to hack instagram online.Pathak, A. (2014). An analysis of various tools, methods and systems to generate fake accounts for social media (Doctoral dissertation, Northeastern University Boston). The revolution is over (2014, November 1st). The Economist. Retrieved from www.economist.com دور جدید کنترل، ارعاب و تهدید فعالان اینترنتی با دستگیری کاربران شبکههای اجتماعی تÙ?دÛ?د Ù?عاÙ?اÙ? اÛ?Ù?ترÙ?تÛ? با دستگÛ?رÛ? کاربراÙ? شبکÙ?â??Ù?اÛ? اجتÙ?اعÛ?">

- Iranian_Censorship_and_Information_Ecologies.pptx: Power Point Presentation

| I | Attachment | Action | Size | Date | Who | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Iranian_Censorship_and_Information_Ecologies.pptx | manage | 7 MB | 10 Jul 2015 - 14:10 | Main.cecilia.anna.andersson | Power Point Presentation |

| |

Table_1.jpg | manage | 62 K | 10 Jul 2015 - 11:31 | Main.cecilia.anna.andersson | |

| |

Table_2.jpg | manage | 87 K | 10 Jul 2015 - 11:35 | Main.cecilia.anna.andersson |

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback