“Hey Alex…”: (Re)constructing Parasocial Relationships with Alex Jones Through YouTube Comment Sections

Team Members

Daniel Jurg

Marc Tuters

Emily Jane Godwin

Matthijs van Dam

David Kabel

Trudi Janssens

Cees van den Boom

Dirk Fens

Gijs Verhoef

Aaron de Rijke

Marta Ceccarelli

Amie Galbraith

Joey Schreuders

Rosa Uijtewaal

Yara van Buuren

Maurice Dharampal

Elena Aversa

Ella Santhagens

Contents

Summary of Key Findings

This project presents the following main takeaways:

-

Alex Jones has a diverse audience that provides hegemonic, oppositional, and negotiated content readings

-

Jones’s audience actively maintains a parasocial relationship with him by calling the content creator by his first name and sending him messages of love in comment sections

-

Controversies around Pizzagate and Trump increase engagement from oppositional audiences, which tend to reinforce conspiratorial thinking rather than provide nuances

-

A novel type of YouTube comment, which we have called the ‘memetic manifesto,’ presents a novel and counter-intuitive way of thinking about how Jones’ audience perceives the YouTube comment section affordance.

1. Introduction

Around 2018, YouTube began receiving heavy criticism for its role in hosting and possibly amplifying extreme right-wing content (Tufekci, 2018). In response, YouTube, along with major platforms such as Facebook, Apple, and Spotify, decided to ‘deplatform’ various ‘extreme’ content creators, such as the infamous conspiracy theorist Alex Jones (Rauchfleisch & Kaiser, 2021). Jones was - and to a certain extent still is - one of America's most infamous and popular conspiracy theorists, earning him the questionable title: 'the most paranoid man in America’ (Bulck & Hyzen, 2020). At the height of his success (2017-2018), the US radio show host and conspiracy entrepreneur raked in around 1.3 billion views on YouTube, compared to 'only' 20 million via his website Infowars.com (Bulck & Hyzen, 2020). The removal of many extreme political channels marked a pivotal moment in a new era of content moderation, with Jones’ removal labeled “one of the biggest purges of popular content by internet giants in recent memory” (Coaston, 2018).

The so-called ‘deplatforming’ of Jones arrived after a broader social discourse on how social media companies were playing a questionable role in online radicalization, disinformation, and the propagation of conspiracy theories (Lewis, 2018). Researchers have begun investigating the effectiveness of deplatforming, focusing on which alternative digital spaces these influencers migrate to and to what extent they can maintain their audience (Rogers, 2020). Or in the case of YouTube, researchers are closely monitoring the recommendation algorithm to locate possible bias and amplification of inappropriate content (Ribeiro et al., 2019).

However, the constant tracing of information flows might hinder some more profound - and lasting - observations about what is so attractive about the deplatformed content in the first place. In other words, some scholars have argued not to fall for technological determinism and to study the (critical) reception of media content (Livingstone, 2019). On YouTube, for instance, much attention has gone to the recommendation engine, but as Munger and Phillips ( 2020, pp. 22-23) have argued: “Models of YouTube politics that focus on the recommendation engine do not tend to focus on comment patterns, relying as they do on a passive audience. We argue a robust comments section indicates higher communal activity on the part of the viewership [...] These interactions, even if contentious, reinforce parasocial relationships between audience and creator and a sense of community between audience members.” Munger and Phillips (2020) conclude that more research should look at how audiences construct a sense of community and parasocial relationship via participatory affordances such as the comment section.

For instance, in the case of Alex Jones, the conspiracy entrepreneur attracted many audiences that engaged themselves with the figure Alex Jones and his content by performing ‘small acts of engagement’ (Picone et al., 2019), e..g. (dis)liking and commenting. The comment section and (dis)like buttons afforded audiences with new ways to express themselves and share their ideas and thoughts with, to a certain extent, Jones himself and other members of Jones’ audience. As Picone et al. (2019) have argued, many social media audiences are by no means inhabiting the ‘prosumer’ ideal that early new media scholars envisioned, but neither are they passive subjects merely consuming algorithmically recommended content. Many social media audiences perform various small interpretative moves reflected in affordances such as likes and dislikes that cost relatively little effort. However, collectively they can create a strong communal sense of belonging.

This project builds on a historical dataset of audience participation with the Alex Jones Channel (2017-2018) captured by Fabio Votta right before Jones was deplatformed. In this DMI Winter School project, we present an exploratory investigation of this dataset to (re)trace audience engagement with Jones in 2017. While our research praxis is mostly rooted in grounded theory, we take the insights of Munger and Phillips (2020) and Lewis (2020) to use the concept ‘parasocial relationship’ as an analytical tool to foster new conceptualizations about radical YouTube audiences.

This investigation into Jones’ audience was divided into four subprojects: (1) Parasocial relationship, (2) Hate Speech, (3) Sany Hook Controversy, (4) Memetic Vernacular. The following methodology and findings section are presented in order of subproject.

2. Initial Data Sets

This project has studied audience engagement with Alex Jones by operationalizing a historical data set of 3,054,103 comments during the height of Jones's success (2017-2018; collected by Fabio Votta). In addition, we also used the titles and descriptions of 21.946 videos from the Alex Jones Channel. We uploaded these datasets into 4CAT to make possible various computational analyses: Alex Jones Channel Comments, Alex Jones Channel Titles, Alex Jones Channel Descriptions.

3. Research Questions

The main research question this exploratory project aimed to answer was: How did audiences engage with Alex Jones’ content on YouTube during the height of his popularity?

We then constructed subgroups that all developed subquestions to provide insight into Jones’ audience:

-

How were parasocial relationships with Alex Jones formed in the comments?

-

Which forms of hate speech can we distinguish in the audience of Alex Jones, and how does this affect the parasocial relationship with him?

-

How did Sandy Hook's controversy destabilize the parasocial relationship between Alex Jones and his audience?

-

Can we find traces of memetic vernacular in audience participation, and, if so, what common characteristics can we discern?

We explored these research questions in four subprojects titled: (1) Parasocial relationship, (2) Hate Speech, (3) Sany Hook Controversy, (4) Memetic Vernacular. The following methodology and findings section are presented in order of subproject.

4. Methodology

This section explains the methodology per subproject: (1) Parasocial relationship, (2) Hate Speech, (3) Sandy Hook Controversy, (4) Rise of the Female Audience, (5) Memetic Vernacular.

4.1 Parasocial relationship

Using Python, duplicates in the initial dataset were removed, leaving a dataset of 1,843,436 comments. To focus closely on the audience’s parasocial relationships with Alex Jones, we filtered the initial dataset in 4CAT for comments containing “Alex Jones,” “AJ” and “Infowars.” This process returned a dataset of 179,154 comments, which we then analyzed through distant and close reading approaches.

Next, we generated word trees in 4CAT. Starting from a specific root query, word trees visualize this query in context, showing the most occurring words and phrases surrounding it (Wattenberg & Viégas, 2008). We used the root queries “Alex” and “AJ” to set the limit of branches to 4 and window size to 5 to generate a large overview of phrases. We then generated a word tree with the root query “infowars” with a limit of 3 branches. All three of these word trees were set to show phrases most commonly appearing after the queries. We generated one last word tree to show phrases appearing before the root query of “Alex,” which shows a limit of 3 branches and a window size of 5.

The corpus was also tokenized in 4CAT using the Twitter tokenizer setting, removing English stop words and lemmatizing the words. We queried the word collocation tool for “Alex” and “infowars” which revealed which words and phrases most frequently co-occurred alongside the selected keywords. Since the “Alex” query showed stronger co-occurrence patterns, we used the data from this query for further analysis for both distant reading and close reading methods. We used the “sort words” option for the word collocations in 4CAT, meaning that we merged different orders of words. For example, this tool merged “Alex” + “love” with “love” + “Alex,” as we were interested in semantics rather than syntax. We then filtered this dataset for the terms that occurred the most frequently. This dataset was imported to RawGraph by a DMI group member from the Density Design Lab, Elena Aversa, who plotted the frequency of the word collocations per month.

The results of the distant reading analysis, the word trees, and word collocations guided us in a close reading of the comments. This entailed an iterative, intuitive and nonlinear approach to analyzing the comments. Hence, close reading was informed by literature as an analytical tool, rather than more strict employment of coding techniques. For example, Picone’s Small Acts of Engagement framework (Picone et al., 2019) aids in characterizing the audience in terms of agency through small acts such as likes and comments in an effort to counter linear understandings of participatory audiences. Such an approach is grounded in theory and aims for a creative and reflexive mapping practice. Furthermore, we made sure to pay attention to possible outliers or counterintuitive uses of the comment section, highlighting breaks in audience behavior patterns.

There are limitations to this research worth mentioning:

-

The focus of this study was Alex Jones, meaning that the results might not be representative of the more extensive alternative influence network. Further research can analyze how audiences react and engage with other political figures on social media.

-

Since the analysis focused on comments, the results reflect the more engaged audience members, namely those who feel the need to comment.

-

Our dataset consists of comments with direct mentions of Alex Jones and Infowars. Therefore, users that do not comment or do not mention Jones or Infowars were not analyzed, and the results are skewed towards seeking engagement with or related to Jones and Infowars.

-

Because we filtered for direct mentions, comments that engaged with Jones or Infowars on a parasocial level without these mentions were therefore not studied.

-

Because the analysis employed qualitative close reading, the results were prone to biases.

4.2 Hate Speech

This subproject draws from different digital methods techniques, both quantitative and qualitative, to answer the question: Which forms of hate speech can we distinguish in the audience of Alex Jones, and how does this affect the parasocial relationship with him?

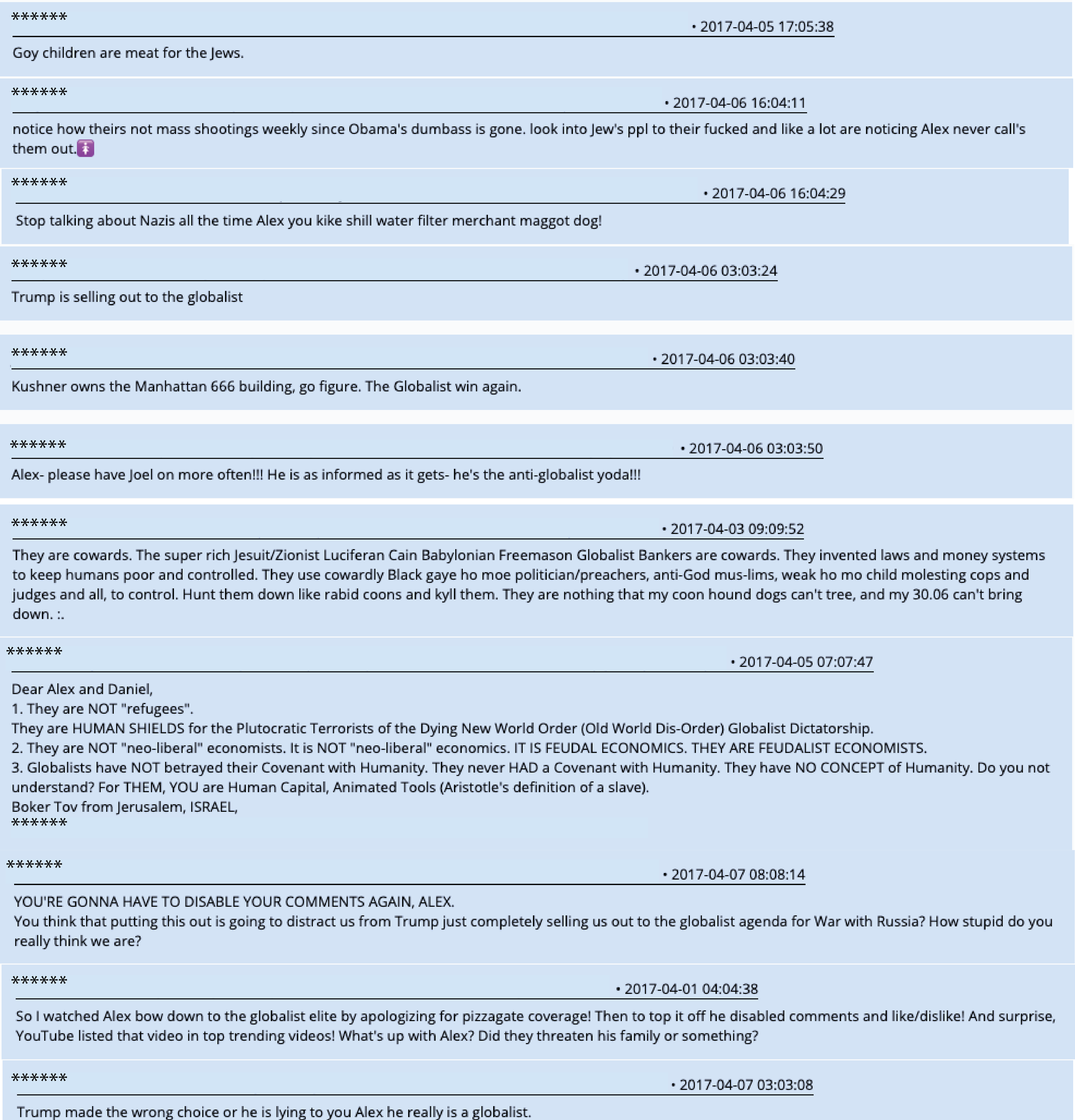

We start our analysis with the most inductive technique to retrieve information about what Jones’ commenters are talking. Using topic modeling on a subset of the data, we analyze the most discussed topics. Second, we study the presence of different types of extreme speech using the extreme speech lexicon developed by Peeters et al. (2020). Finally, we close-read the comments using antisemitic slurs in April of 2017. As we saw earlier (REF group 2), this month is of interest because it appears that Jones’ audience became slightly less supportive of him, and in the same month, the amount of antisemitic comments increased sharply.

Figure 1: Methodology flowchart hate speech project

4.3 Sandy Hook Controversy

To assess how Alex Jones’ audience engaged with the controversy surrounding his Sandy Hook conspiracy theory, we used a combination of dataset filtering and qualitative close reading (see Figure 1).

Figure 2: Methodology flowchart Sandy Hook Controversy Project

We first filtered the original dataset (devoid of duplicates) only to include comments referring to the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings. To do this, we used the filter by wildcard option in 4cat to create a dataset retaining only posts that match one of a list of phrases (resulting in 2,185 items). The phrases included the name of the school, the name of the killer, the name of the school’s principal, and the name of the killer’s mother (one of the many victims): “Sandy Hook, Adam Lanza, Dawn Lafferty Hochsprung, Nancy Lanza.” This ensured that the resultant dataset disregarded comments referencing other, but similar conspiracy theories yet included relevant comments that did not specifically refer to the school's name. To further explore the dataset, we produced a simple frequency histogram (Figure 2). The histogram shows a clear peak in comments during June 2017, which led us to discover that Alex Jones publicly backtracked on his Sandy Hook conspiracy theory during this period. Perhaps this ignited a resurgence of audience engagement related to the event. This also linked well with another one of this project’s subgroup’s findings, with the frequency of the word “love” in the dataset beginning to fall from June 2017 with a di in July 2017 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: A monthly histogram of comments on Alex Jones’ YouTube videos related to the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting posted from January 2017 to December 2017.

Figure 4: A monthly histogram of comments on Alex Jones’ YouTube videos related to the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting posted during June 2017.

As we wanted to perform a qualitative close reading, it made sense to filter the dataset further to include just the month of June. The resultant dataset included 1,066 items. We produced a second histogram using this dataset, which shows spikes in comment frequency from the 12th to the 20th of June. After some research, we discovered two specific videos that were publicized during that time period. On the 12th of June 2017, NBC released a preview of an interview their host Megyn Kelly interview with Alex Jones, which saw him hesitate when asked about his opinion that Sandy Hook was a hoax (Hauser, 2012). On 18th June 2017, Alex uploaded a Sandy Hook video to his YouTube channel whereby he sent condolences to the victim's parents (Warzel, 2017). Shortly after, on that same day, NBC aired the whole interview. Again, this linked well with another one of this project’s subgroup’s findings, with the frequency of the word “interview” in the dataset showing a clear spike in June 2017 (see Figure 4). These discoveries led us to focus our close reading on Alex Jones’ backtracking of the Sandy Hook conspiracy and his audience’s reaction to it, as will be better explained in the Findings/Discussion section.

4.4 Memetic Vernacular

Due to the de-platforming of Alex Johnson's channel, the research suffered from the lack of a complete image at the exact moment these videos were generating interactions. To access such historical data, the research employed the Wayback Machine platform as a source for “digital history” (Rogers, 2017) useful to capture the aesthetic of Youtube in 2017. Specifically, the aim was to investigate audience participation and thus define a taxonomy of both the content shared and the structure of such content.

As shown in figure 5, the methodology was structured as follows:

-

analysis of the top 25 longest comments in terms of structure and theme

-

analysis of the videos where the top 25 longest comments were posted

-

analysis of the edits in the corpora of the top 7 longest comments.

Figure 5: Methodology diagram of the memetic vernacular project

5. Findings/Discussions

5.1 Parasocial relationship

To understand the audience engagement with Alex Jones, we began with a frequency analysis of terms related to Alex Jones. Within the filtered dataset of 175,154 comments, the word “Alex” was used 156,767 times, “Infowars” 36,066 times, and “AJ” 4,766 times, showing a clear preference for addressing Alex Jones on a personal basis. Following this, the word tree queried for “Alex” showed that “Alex” is used in both supportive and adversarial phrases. Following the combination “Alex is”, “on fire” was a prevalent following phrase, but a variety of phrases suggesting Alex is regarded as an “actor” or “shill” were also among the top results. This word tree is visualized in Figure 6. The word tree queried for words and phrases before Alex (Figure 6) showed an overall positive view of Alex, with “love you” and “thank you” as the most prominent phrases before Alex. Tellingly, the word tree for Infowars (Figure 7) almost entirely consists of negative phrases, with “Infowars is fake news” being the top result in this word tree.

Figure 6: Key-word in-context for ‘alex’

Figure 7: Key-word in-context for ‘infowars’

After running the collocation analysis, we obtained a dataset containing the 15 terms most often associated with “Alex.” We then filtered the dataset only to include the six most frequent associations, filtering out too general terms and had a relatively low frequency such as “people” or “video” to remove noise from the graph. This dataset is visualized in Figure 8, displaying the six most frequent associations with “Alex” over time.

Figure 8: Word collocations for ‘alex’

From the word collocation analysis, “love” appears to be the word most frequently associated with Alex. The prevalence of this association changes over time. The first peak of “love” corresponds to Alex Jones’ birthday in February, as also visible from the collocation to the word “birthday.” Dips in the frequency of “love” corresponded to other findings made during our DMI Winter School project on certain controversies regarding Alex Jones. This matched with the pattern of frequency of the keywords “Trump” and “interview.” “Hey” was also one of the most frequently associated words with “Alex,” and this association remained substantial and constant throughout the entirety of the recorded year. “God” was also a relevant term within the comments, especially during the first months of 2017.

The findings above informed the subsequent close reading process. To understand how parasocial relationships were being formed, we began taking note of recurring themes throughout the comments. Firstly, we noticed threads of advice-giving, in which users felt compelled to leave suggestions for Alex and his team on both the show and on matters such as health, or safety.

WOW! Alex is on FIRE!!!! Infowars is unplugged! AWESOME! Alex you should have a new youtube channel rated "R" where you can swear and flip out like this! I would subscribe! Love it! (2017-02-03). Alex you need to hire Katie Hopkins, she's awesome (2017-09-15).Mentions of “love” were also frequent in these comments, and strong feelings of love were often also connected to religious beliefs. Some viewers did not simply “love” Alex, they believed that Jesus also loved him, that God was behind Alex’s messages.

Hey Alex, rest up to fight another day. (...) Love you as a blood brother, Jeff (2017-01-03). I love you Alex and Lord Jesus Christ loves you to. Lord Jesus Christ has our backs. Thank the Holy Spirit Jesus Christ our Lord for this truth (2017-11-09). Hey Alex, If I walked into a cafe and you were there with guests or crew, would tell waitress to give me your check. Be honored to pick up the tab (2017-01-04).

The advice included not only messages of support but also disapproval. Frequently, it appeared that viewers who were holding such opinions used to be fans of Jones who began to change their minds about his videos:

Alex you shouldn't have censored the Flat Earth video with Eddie Bravo. YOU are CENSORING (2017-03-22).Lastly, we noticed surprising stylistic variation in the comments left by users. For example, some users wrote long comments containing multiple paragraphs, with over 23 comments being at least 1,000 words long (see excerpt below). Both the longest comments and other atypical ones often employed odd syntactical features (e.g., repeated use of ellipses or other punctuation, entire text in uppercase), treating comments ranging from their deep love or hate for Alex Jones to complex elaborations to conspiracy theories. Some of the authors of these unusual comments were re-occurring commentators. This was the case for the author of the following comment, who had left 37 comments throughout the year, writing all messages in capital letters:

I feel like I have lost a ill respect for Alex and I been a fan for awhile but with this video and my own research the things that he is saying isn't matching up with what the Q drops are only 10 people know exactly what going and definitely not a source that Alex have! Alex you don't always need to take credit and be all knowing Q is by far the best drops that has happened in a long time and no Zach is not Q For q followers be careful on the info you take in cause there is alto of things in this video is not true its actually sad since I am a fan if alex (2017-12-24 21:09:14).

As usual, you have to open your mouth Alex when people are talking. Shut the hell up so we can hear!!! (2017-06-24).

Following the more disapproving voices, we identified patterns of heavy criticism. Such comments were sometimes coming from viewers holding more moderate views than Jones, mostly from those who thought he had lost his extremist or controversial edge. Audiences often included themes of antisemitism and other terms related to conspiracy theories in these comments, such as “controlled opposition,” “globalist,” “zionist,” or “shill”. lately im becoming more convinced alex is controlled opposition good bye to the real issues! good bye to taking the trump admin to task and holding their feet to the fire! trump aint shit hes a puppet just like the rest even if he was genuine at first which he wasnt the globalists and the neo cons got their tentacles deep! ever so often i come back and watch info wars and alex and its getting worse by the day! come on alex you old shill youuu tell atleast 10% truth like you used to! (2017-05-03).

Infowars is IN BED with all these pedo Satanists!!! Paul Joseph Watson might as well put a damn hood on his head like all those damn blokes pretending to be Muslim terrorists. This entire setup is *controlled opposition with it's troll comments and FAKE health snake oil garbage!!!* (2017-06-07).

"Hijacking globalism" ???????????? Alex you are one of the biggest fraud on the planet. You are a globalist just like Trump (2017-05-01 09:09:53). Just say you are a Zionist pig alex. Fucking coward. Pizzagate is real (2017-03-24).

STOP TALKING NONSENSE ALEX I CURSE YOUR WORDS AND I SPEAK DEATH TO EVERY UNBORN SEED IT WILL NEVER HAPPEN TO TRUMP!!!HE IS GODS CHOSEN VESSEL. THESE ZIONIST TRAITORS ARE NOT STRONG THEIR WEAK. THEY ARE ALL UNDER MIND CONTROL PROGRAMMING AND THEY LIVE IN AN UPSIDE DOWN DELUSIONAL INVERTED BIZZARO WORLD UNREALITY. THEY ARE NOT COMING AGAINST TRUMP HE IS JUST A VESSEL GOD HAS CHOSEN TO USE....THEY HAVE NO CHANCE OF VICTORY AGAINST GOD.GOD MADE LUCIFER. HE IS NOT A GOD BUT A DELUDED FALLEN ANGEL THAT WAS DEFEATED 2000 YEARS AGO. ITS THEIR JUDGEMENT WRATH TIME. THE "AROUND 2000" PIGS THAT WERE RAN INTO THE SEA AT GADERENES REPRESENTED YEARS. THEIR TIME IS UP BY THE END OF 2018 THERE WONT BE ONE OFFSPRING LEFT AMONGST THEM (2017-08-08).

Excerpt from a comment (original length: 1,533 words):

I tried to contact InfoWars today, I would like to share this ground-breaking realization I've had concerning the events and how they interrelate. The reality is the most frightening thing I've seen, far beyond my ability to imagine, yet I believe it's absolutely true and all ties in together. I have been studying this issue extensively for a long time, and recently made a break-through/epiphany so horrifying, I don't know what to do about it. I apologize for the length, but wanted to describe it in detail, as I am sadly certain, all the pieces of the Geo-political puzzle fit exactly this way, and lead to no other conclusion. I would ask you to think about it, and write about it should you deem it worthy (2017-03-20).

Our analysis reveals that during Alex Jones’ final year on Youtube, his audience was not monolithic. Diverse emotions were displayed, from positive to negative, as seen in the word trees, and criticism rose and fell during this final year depending on his actions, as seen in the word collocation graph over time.

The comments featured a wide range of interactions with Alex Jones and many intense displays of emotion. Commenters frequently declared their love for Alex, referring to him as a friend or even a “brother.” Indeed, “love” is the most commonly associated word to Alex, shows that a large part of the audience was very fond of him during this final year. However, while no negative words were among the top six most prominently associated words with Alex, there was still a plethora of criticism aimed at Jones. The use of terms such as “controlled opposition” and “actor” suggests that some commenters viewed Jones as a tool to discredit or control the alt-right narrative. The multitude of different interactions and reactions in our findings suggests a much more complex and sensitive audience than earlier research by Hyzen and Bulck (2021) implied, and a certainly more active and invested, rather than passive, audience as suggested by Lewis (2018).

Overall, Alex Jones' audience demonstrated strong parasocial relationships. The comment section functioned as a place for the audience to engage in a conversation with Jones directly, despite the fact that Jones would most likely not respond to or even read their comment. This was shown in the way that many comments began with “Hey Alex”, as if the audience members were on a first name basis and knew him personally.

This personal connection is also reflected in the fact that Infowars was mentioned much less frequently than Alex, suggesting that Jones’ audience was invested in Alex as a person, rather than in his brand. Even negative comments mentioning Alex were often still very personal and familiar, suggesting that he should rest or change his behavior for better results. This form of critique implies that many in the audience wanted to stay attached to him even when they might not have fully agreed with him and were rooting for his success. In contrast, Infowars was also critiqued but was rarely complimented, suggesting that commenters directly aimed their praise at Alex.

However, some acts of engagement were not small at all. While many simply left short comments, our analysis of atypical commenting patterns showed that users interpret and engage with the YouTube comment section in differing ways. The long, conspiratorial comments read as manifestos for no one to read. In the depths of the comment section, a place hardly visible to most users or creators, parts of Alex Jones' audience were screaming into the void, perhaps hoping to get an answer from Jones himself. Once again, previous understandings of what a YouTube comment is and what a YouTube audience is were challenged by the effort-heavy public of Alex Jones.

5.2 Hate Speech

In this second analysis, we present the topics discussed in the comments section of Jones’ videos on YouTube in 2017, using topic modeling techniques. As Table 1 shows, of the ten clusters, five clusters show good cohesive topics: religion, media, politics, the Infowars channel itself, and interviews. The other five clusters look similar to the ones we call miscellaneous.

| Religion | Media | Politics | Infowars | Interviews | Miscellaneous |

| god | truth | trump | infowars | love | people |

| bless | watch | president | medium | guest | war |

| child | hope | america | hate | interview | time |

| jesus | attack | obama | news | interruption | american |

| white | msm | country | support | friend | government |

Table 1: Keywords clustered by topics

These word clusters not only show the issues commenters mostly talk about, it already gives us a sense of the way they are being discussed. Note that these interpretations need further qualitative analyses that have not been feasible within the timeframe of this Winter School. For instance, the word ‘white’ shows up in the cluster' religion.' This may point to a linkage between religion and race. When the topic ‘media’ is discussed, the discussion seems to focus on tension (attack) between the mainstream media and other outlets (MSM) about what is true and what is not (truth). In the topic ‘politics,’ it is striking that former president Obama still plays a big role because, in 2017, he was no longer president. There also seems to be contention when it comes to ‘Infowars’ because of words like ‘hate’ and ‘support’. The topic ‘interviews’ shows mostly neutral terms when discussing Alex Jones’ interview videos. Only the word ‘interruption’ gives a sense of some of the commenters' gripes.

To get closer to the ideas behind the extreme speech of Jones’ commenters over time, we used different queries of extreme speech developed by Peeters et al. (2020). These queries reflect different pinnings of hate speech often found in extreme, right-wing internet culture, which also can be found in the comments of Jones’ YouTube videos. This analysis considers anti-left, anti-semitism, anti-disability, homophobia, misogyny, racism, anti-conservatism, anti-lower class, and sexual, but for clarity of the figure, we only included the five most prominent forms of hate speech in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Hate-speech analysis

Misogyny is in most months the most prominent form of extreme speech in 2017, with spikes in January, June, and October. The word primarily used in this context is ‘bitch’. According to close-reading, the peak in June is most likely due to an interview of Megyn Kelly with Alex Jones in which she asked questions about the Sandy Hook conspiracy. This seems to have led to several negative comments towards her, using misogynistic slurs.

In April of 2017, there was also something interesting going on. In chapter 2, we saw a decrease in the word collocation between Alex Jones and ‘love’ and a sharp increase of collocation between Alex Jones and Trump. In the same month, antisemitic slurs increased in the comments, and according to our preliminary close-reading efforts, the decrease of love and the increase of Trump and antisemitism could be connected.

Figure 10: Examples of close reading antisemitism comments April 2017

At the beginning of April 2017, then-president Donald Trump launched a missile strike against Syria. During Trump’s foreign intervention, Alex Jones supported him, upsetting the more isolationist part of his audience, As some of the comments listed in Figure 10 reveals. The intervention by Trump put Jones in a difficult position. As he kept on supporting Trump, we see part of his audience moving away from Jones and calling him a ‘globalist’, which in this part of internet culture is an anti-Semitic dog whistle (Peeters et al. 2020). On the other hand, if Jones had stayed true to his more isolationist/antisemitic base, he probably would have upset the part of his base who felt more strongly about supporting Trump throughout this action. It shows how Jones’ audience has opinions of their own and calls out Jones if he does not say or do what is in line with their worldview. In moments of controversy, this can put Jones between a rock and a rock and a hard place.

In conclusion, the comments section of Alex Jones YouTube videos is a lively place where there is a lot of discussions and where people have their own opinions and visions of the topics Jones discusses. The comments are mainly about politics, religion, and the media. Forms of extreme speech are at the surface, with misogyny, antisemitism, and anti-left as the most prominent angles. Jones’ audience is not taking everything he says as the only true vision of current affairs. In times where Jones takes a position on controversial issues for his audience, for instance, when he chooses between supporting Donald Trump or staying true to a more American isolationist position, Jones is doomed to alienate part of his audience. Further analysis is necessary to gauge the extent of the alienation if this is a temporary or a permanent response, and whether Jones may also gain a new audience when he loses a part of what he had.

This part of the research is paralleled by the fallouts mentioned in the sentiment analysis in other research sections. The decrease in ‘love’ and increase in ‘Trump’ keywords are paralleled by the rise of antisemitism. During these turmoil situations, the antagonization of the audience between Jones, Trump, and among themselves thus also increases. Alternatively, the rise in misogyny around June 2017, paralleled by the turbulent situation around Alex Jones and his shifting views regarding Sandy Hook.

5.3 Sandy Hook Controversy

This third subproject sought to explore how the controversy surrounding Sandy Hook destabilized the parasocial relationship between Alex Jones and his audience. Alex Jones famously claimed that the Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings were a hoax. However, he openly backtracked on this claim in June 2017. In a video uploaded by Alex Jones on 18th June 2017, he sent his sincere condolences to the parents of the Sandy Hook victims, and in an interview aired on NBC News on 18th June 2017 (and previewed on 12th June 2017), he was hesitant to support his initial claim when questioned by host Megyn Kelly. He also deleted old videos related to his initial Sandy Hook conspiracy theory claim from his channel. We predicted that, rather than following him in his attempt to nuance his Sandy Hook conspiracy theory, a large proportion of his audience do the opposite: radicalizing against him. We expected to see this portrayed in Jones’ YouTube comments in June 2017.

From a close reading of the comments posted on Alex Jones’ YouTube channel between the 12th and the 20th of June 2017 -- although there were audience members that continued to show their support -- we did find evidence that many of his audience members “turned against” him:

"There might be tapes." Alex is so pathetic. I have been a hardcore follower since 2012. But him acting like Sandy Hook was real now when he used to call it out as fake and staged. Him backing off Pizzagate and siding with the deniers when ten minutes of research make it evident it's legit, him doing crap that obviously beforehand only will hurt his brand and the truth media and then him supporting Trump even though Trump has been doing crap that helps the NWO is too much to ignore and be quiet and be a good little fan. Why is no one else calling him out? Why do people keep saying "I support Alex and Trump (2017-06-12). Sandy Hook was a complete hoax, Alex, and you KNOW it! How dare you lie like that, and say you think it did happen, that it was real??!! PUSSY! (So what makes YOU any different than them? Remind me)? You have/ had a responsibility to speak the truth, about Sandy Hook, et al. Not cherry-pick which propaganda to fall in step with and which to call out as fake! (And then claim to be a preacher of the truth, and that you stand up against the globalist lies). Really disappointing, Alex. Like your: 'pizzagate is not real' BS. Stop playing both sides!! (2017-06-16). "You have cowered down on Sandy Hook, Something is shady. Things don't add up with the SH situation and you are becoming a sellout (2017-06-19).

We also found a lot of comments specifically referring to Megyn Kelly:

Sandy hook is totally fake Alex! You know it is so you should have said it instead of backing down in front of that whore! (13-06-2017).

As well as evidence that Alex had deleted some of his older YouTube videos related to Sandy Hook:

What happened with the Sandy Hook Vampires video? It just vanished? Are you being censored? (2017-05-26). See Figure 4 below for a visualization of these sorts of comments.

Figure 11: A visualization of some of the comments of Alex Jones’ YouTube channel related to the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting posted from 12th June 2017 to 19th June 2017.

Overall, the comments worked to illustrate a somewhat radicalization of many of Alex Jones’ audience members, as they displayed anger towards Alex as a “coward” and subsequently sought to further push for the “Sandy Hook is a hoax'' conspiracy theory Alex started. Further analysis is necessary to understand better the audience dynamic related to the controversy surrounding the Sandy Hook conspiracy and Alex’s backtracking, as it seemingly destabilizes the parasocial relationship between Alex Jones and his audience evidenced previously in this report.

5.4 Memetic Vernacular

Finally, to get a picture of the 'less-visible' and uncommon comments, we focused on those with the highest number of characters in the dataset. The analysis was limited to only the first 25 results, making it easier to study the content without employing any machine learning software.

In addition to the content and structure of the comments, we also examined the accounts that produced them. The resulting clusters were the following:

-

available: including all the accounts still accessible at the time of the analysis

-

terminated: with regards to the accounts terminated due to violations of Youtube’s policy (against spam, deceptive practices, and misleading content)

-

non-existing: referring to the accounts unavailable at the time of the analysis.

As a result, it was possible to identify nine available accounts that wrote fourteen comments, two terminated ones that instead produced nine comments, and one non-existing account that contributed with only one comment (see figure 12).

Figure 12: Top 25 longest comments by author, status, length, structure, and theme

Regarding the themes, it was possible to structure the results into three macro clusters:

-

"America First" manifesto: a lengthy manifesto whose content mainly refers to a positive view of Trump's actions during his term in office (see figure 13)

-

"No Muslims" manifesto: sharing disinformation about Muslims (see figure 14)

-

“Roman Catholic Church essay”: an extended “essay” on the “endless battle against evil” (see figure 15)

Figure 13: example of one of the comments belonging to the “America First” Manifesto cluster

Figure 14: example of one of the comments belonging to the “No Muslims” Manifesto cluster (corpus is cut due to the length of the comment)

Figure 15: example of one of the comments belonging to the “Roman Catholic Church” Essay cluster

Finally, we clustered the comments in three main groups (see figures 12 and 16) depending on the corpus structure:

-

paragraph: including the comments organized in paragraphs

-

collection of quotes: particular comments organized in a long list of quotes

-

wall of text: no division in paragraphs, but a long dense corpus of text.

We may assume that there is a common pattern in audience participation: the three main themes are repeated by different accounts and shared on various videos, and the length and structure of the texts, which are shared across comments (see figure 16).

Figure 16: Top 25 longest comments by corpus structure (accounts are divided by status: Available - green, Terminated - red, Non-existing - black)

For a more detailed picture of such participation, we focused on the top 7 comments by length, all organized in paragraphs(see figure 17), and this eventually confirmed the presence of a memetic vernacular.

Figure 17: Top 7 longest comments by corpus structure: the “America First” Manifesto

In fact, there are seven different versions of the so-called “America First” manifesto, which refers to the slogan that has become popular during President Donald Trump's term in office. Each comment, posted by two different users and on seven different videos of the Alex John channel, is the edited version of the previous one, with changes both in sentences and in the order of the paragraphs (see figure 18). This “drafting the manifesto” approach ultimately seems to confirm the presence of common patterns in users' activity as assumed with the original research question.

Figure 18: Top 7 longest comments by corpus structure: edits in the paragraphs of the “America First” Manifesto

The last step in researching the memetic vernacular of audience participation is giving a broader picture of such a phenomenon by employing the Wayback Machine to have the perception of the context in which such comments were posted. Figure 19 shows all the captures stored on the Wayback Machine in the last four years, while figures 20-21 present an example of a snapshot of a video from Alex’s channel together with the longest comment posted on it.

Figure 19: Number of snapshots stored on the Wayback Machine per video (Videos where the top 25 longest comments were posted)

Figure 20: Snapshot from the Wayback Machine on the most “snapped” day in 2017

Figure 21: Longest comment for the video

6. Conclusions

Our project set out to investigate how Alex Jones’ audience engaged with his YouTube content during his final - most popular - year, paying attention specifically to: (1) how the comments contributed to forming a parasocial relationship, (2) which forms of radical engagement can be distinguished, (3) how the Sandy Hook's controversy destabilized the parasocial relationship, (4) how Jones’ markets his videos, and (5) mapping the specific memetic vernacular in audience participation. We employed a mixed-methods approach to a historical dataset of audience engagement with the Alex Jones Channel to provide insights into these areas, combining computer-assisted distant readings with 4CAT and close reading practices.

Overall, the analyses reveal that Jones’ audience is diverse and dynamic. Opposition is present alongside support, contributing to mixed yet highly emotional reactions to Jones’ content. Counterintuitively, we found that some viewers perceived the affordance of the comment section as a forum, a space to voice opinions through the form of long and elaborated messages rather than short reactions (as is primarily visible at the top of the screen for users when filtered on ‘relevant’). Conspiratorial themes intertwined with advice and love declarations directed at Jones, signaling a high devotion to Alex Jones as a person rather than a brand. However, feelings of love were never stable, as viewers’ opinions changed and evolved alongside various events of which Alex Jones was the main character. Whether they asked Jesus Christ to protect Jones, accused him of being controlled opposition, or fantasized over imagined acts of chivalry, most commenters developed a complex and ever-changing parasocial relationship with Alex Jones.

The results of this exploratory study highlight a few critical areas for further research. First, since strong parasocial relationships were evident, more investigation into the role of parasocial relationships on the success and popularity of conspiratorial content would be fascinating. Furthermore, more research is needed to understand better the complex community dynamics surrounding conspiratorial content, both on Youtube and other social media platforms. This includes using historical datasets of or relating to deplatformed content creators. This should all be part of a broader effort of researchers to archive YouTube content and critically analyze the dynamics of content that is deemed ‘too radical’ for platforming.

However, these efforts are only possible when researchers have access to deplatformed data. The main issue with continuing our research efforts is that deplatformed content is often inaccessible. We were lucky to have Fabio Votta capturing Alex Jones' data before YouTube removed his channel. As researchers, we should both pressure YouTube to share more data with researchers and start archiving political YouTube ourselves. This new era of deplatforming and content moderation calls for a contemporary research praxis that anticipates such events and develops methodologies to reconstruct (radical) narratives and their impact. Archiving and closely studying deplatformed content is a research effort we hope to continue in the future.

7. References

Arthurs, J., Drakopoulou, S., & Gandini, A. (2018). Researching YouTube. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 24(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517737222

Burgess, J., & Green, J. (2018). Youtube: Online video and participatory culture (Second edition). Polity Press.

Christin, A., & Lewis, R. (2021). The Drama of Metrics: Status, Spectacle, and Resistance Among YouTube Drama Creators. Social Media + Society, 7(1), 205630512199966. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305121999660

Coaston, J. (2018, August 6). YouTube, Facebook, and Apple’s ban on Alex Jones, explained. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2018/8/6/17655658/alex-jones-facebook-youtube-conspiracy-theories

Lewis, B. (2018). Alternative Influence. Data & Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/library/alternative-influence/

May, A. L. (2010). Who Tube? How YouTube ’s News and Politics Space Is Going Mainstream. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 15(4), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161210382861

Peeters, S., & Hagen, S. (2018). 4CAT: Capture and Analysis Toolkit (1.0) [Computer software]. https://4cat.oilab.nl/

Peeters, S., & Hagen, S. (2021). The 4CAT Capture and Analysis Toolkit: A Modular Tool for Transparent and Traceable Social Media Research. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3914892

Picone, I., Kleut, J., Pavlíčková, T., Romic, B., Møller Hartley, J., & De Ridder, S. (2019). Small acts of engagement: Reconnecting productive audience practices with everyday agency. New Media & Society, 21(9), 2010–2028. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819837569

Rauchfleisch, A., & Kaiser, J. (2021). Deplatforming the Far-right: An Analysis of YouTube and BitChute. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3867818

Rogers, R. (2020). Deplatforming: Following extreme Internet celebrities to Telegram and alternative social media. European Journal of Communication, 35(3), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120922066

Rogers, R. (2017). Doing Web history with the Internet Archive: screencast documentaries. Internet Histories, 1(1-2), 160–172. doi:10.1080/24701475.2017.1307542

Van den Bulck, H., & Hyzen, A. (2020). Of lizards and ideological entrepreneurs: Alex Jones and Infowars in the relationship between populist nationalism and the post-global media ecology. International Communication Gazette, 82(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048519880726

Hauser, C. (2017, June 12). Megyn Kelly Calls Alex Jones’s Sandy Hook Denial ‘Revolting,’ but Still Plans to Air Interview. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/12/business/media/megyn-kelly-alex-jones-newtown.html

Warzel, C. (2017, June 18). Alex Jones Just Released A Father’s Day Video To Sandy Hook Parents—But Didn’t Apologize. BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/charliewarzel/alex-jones-just-released-a-fathers-day-video-to-sandy-hook

| I | Attachment | Action | Size | Date | Who | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Close_reading_exports.png | manage | 388 K | 18 Jul 2024 - 09:13 | DanielJurg | |

| |

Interview_anonymized.png | manage | 191 K | 18 Jul 2024 - 08:42 | DanielJurg |

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback