You are here: Foswiki>Dmi Web>WinterSchool2020BeautificationApps (31 Jan 2020, AnneHelmond)Edit Attach

Beautification Apps

A Cross-Country Analysis Regarding Face Modification Features

Team Members

Team members: Shemayra Bastiaanse and Dania Awin Part of the project: 'Apps and Their Practices: A comparative issue analysis across app stores and countries' Facilitated by Esther Weltevrede and Anne HelmondIntroduction

“All I know, is everything is not as it’s sold” is the very first sentence singer Nelly Furtado sings on her hit song ‘Try’ (Genius). Whereas this statement is applicable to many things, it can certainly be said about today’s culture of digital images, since the majority of pictures showed in mass media are digitally edited (Guest 1). Whereas technologies concerning the editing of pictures used to be available for a small crowd only, for example for people working for magazines or in the world of advertisement, nowadays the general public has access to methods to easily alter their own appearance as well (Rajanala et al. 443). More specifically, today most individuals edit their pictures to show an ideal appearance of themselves before uploading these on social media platforms, whereas most altered images mirror Western beauty ideals (Guest 1). This research dives into some of the methods which offer many individuals the ability to easily edit images themselves by using the touchable screens of their tablets or smartphones by investigating the Google Play Store and the apps they provide concerning beautification, which refers to “the process of improving the appearance of someone or something” (Cambridge Dictionary). More specifically, this research provides a cross-country analysis 3 examining Google Play Store, the applications offered and the features these applications include across three different countries: the United States, India and Brazil. Through examining the topic of beautification apps, this research aims to find out the differences and similarities offered concerning face modifications by answering the following research question: ‘What are the differences and similarities of digital face modifications proposed by beautification apps in the Google Play Store of Brazil, India and the United States?’ To answer this research question, this paper analyses screenshots gathered from top ten results concerning beautification apps by searching for both ‘Beauty’ and ‘Beauty editor’ in English, Portuguese and Hindi by using the Google Play Stores located in India, Brazil and the United States as its source. Furthermore, several academic texts will be used, among which ‘Multi-Situated App Studies: Methods and Propositions’ by Michael Dieter and colleagues in which they write about apps stores and how these operate. Additionally, ‘Gender differences in gratifications from fitness app use and implications for health interventions’ by Saskia Klenk, Doreen Reifegerste and Rebecca Renatus. In this text Klenk et al. refer to gender differences and how genders are being approached in relation fitness applications.Theoretical Framework

The text ‘Multi-Situated App Studies: Methods and Propositions’ by Dieter et al. will be used as basis for the analyses mentioned in the following chapter. It explains that App stores are the primary source to get access to apps and grant researchers multiple beginning points to understand the outlooks of several stakeholder parties, as well as users and distributors. Therefore, the app store behaves as a gatekeeper, that makes the guidelines for app development, categorization and circulation with its goal to reach a high visibility to get more consumers (2). The interface of apps provides researchers with access to analyze potential user processes. Interface research provides insights about the workings of apps and above all it illustrates how particular beliefs about users are integrated in the app design. With other words, apps design their interface in such a way that corresponds with prejudices they have of their users (4).Face Altering: Skin Color

To answer the research question, the element of skin color satisfaction and alteration amongst women will be further examined by looking into worldwide skin tone standards. They reflect the importance that skin tone, as well as body figure, have regarding female beauty (Craddock 287). According to Nadia Craddock several documentations have proven that many societal and cultural factors affect how people perceive their skin color, which can have impact on the attitudes regarding skin color standards. This can subsequently produce internal disapproval that can result in dangerous practices like skin bleaching and skin tanning. Fashion, media and advertisement encouraged the ideal of tanned skin as a part of the perfect Western female appearance. In the United States 30 million people engage in tanning practices yearly, whom 70% consist of Caucasian women. A profound number of Caucasian women find their skin to be to light and deliberately seek tanning practices. Contrary, women with darker complexion identify lighter skin with what is deemed the perfect beauty ideal. Nevertheless, in the case of women of color the desirability for a lighter skin goes further than just appearances. Matters regarding racism and colorism play a role in the preference to have a lighter skin. The history of colonialism left a trace of colorism, where lighter skin has more authority and an advantage (287). The dominant Western beauty ideals and the damage darker skinned girls face leads to a growing global billion-dollar industry offering skin lightening. The marketing around skin lightening promotes good looks and happiness if consumers use their lightning products. The popularity of skin whitening appears to be especially high in among 60–65% Indian woman, 77% Nigerian women and 83% woman from Thailand. On top of that, skin lightning companies produce unrealistic beauty standards by digitally enhancing and changing the skin color of their models to fit the fair skinned ideals (288).Photo modification

In ‘Selfies—Living in the Era of Filtered Photographs’ Susruthi Rajanala et al. explains that the popularity of mobile beauty edit apps and the growing number of altered selfies changed the general viewpoint of the hegemonic beauty norms. Social media platforms like Snapchat and Facetune provide users with various filters and give a range of tools to alter one’s appearance. Before photo editing tools where available to the common public, this was exclusively applicable to celebrities. Resulting in the admiration of a perfect image that the general could not reach. In present times, social media platforms offer every user to reach their perfect picture by giving access to editing tools. Current research implies that young women that alter their photos frequently, more often display disapproval to their appearance. The study further explains how people with body dysmorphia use social media as a means to get acceptance. Lastly, the study states that people who actively present themselves in a certain way on social media and engage in the like and comment culture, have a higher chance to not favor their appearance. Consequently, photo altering practices lead to an increase in plastic surgery. In the past people showed pictures of celebrities to their plastic surgeon. Nowadays people want plastic surgery to look like their altered pictures, with bigger lips, smaller noses and so on. This is called “Snapchat dysmorphia” (Rajanala et al. 443). Social media apps have created new ways to alter appearances and thus changed the general beauty ideals.Gender targeting

According to Klenk et al. to assure efficient user usage of health application, particular groups are targeted. This appears to be aimed to reach gender specific groups. An example of this are game applications where they push physical exercises on to males. In addition, dissimilarities between gender are noted in social media habits, user intention and mobile phone gratifications. In the case of health apps, it seems like the motives between men and women are different. Whereas female users are driven by looks, weight and health, their male counterparts are motivated by power, championship and challenge (179). Even though Klenk et al. discusses the gender differences in health apps, this can also apply to the gender targeting in beautification apps, as they seem to target users according to their gender users.Methodology

To collect all data necessary to answer the research question, this paper includes academic literature. Additionally, this research includes an analysis of screenshots regarding beautification apps presenting the features facilitated through the apps. These screenshots have been gathered by using the Google Play Store with the United States, India and Brazil as its location. By using the Google Play store as the source of all screenshots, ‘Beauty’ and ‘Beauty editor’ have been searched for within the app store in English, Hindi and Portuguese. The three countries have been selected, because these countries represent the top three most active countries regarding app downloads (Briskman 2019). While only English search queries were used to gather data in the United States, both English and Hindi were used while examining the Indian Google Play Store, since India used to be a British colony and both languages are still commonly spoken (Szczepanski 2020, Daniel 2000). However, despite the fact that Portuguese is spoken by 97.9% of Brazil’s population (Pariona 2018), this research includes the English search queries for the Brazilian Google Play Store as well to view whether or not there would be major differences in the results. To collect the screenshots used to analyze the face modifications facilitated by the beautification apps, the search queries were looked for in the different app stores in all languages relevant to that specific country. Then all ‘app ID’s’ (authentical names related to the applications) of the top ten results per country and per search query were selected either by using the link ripper tool and copying the app ID into a spreadsheet or by copying and pasting the app ID from the link into a spreadsheet. Thereupon all screenshots concerning the top ten for each country and search query were scraped by using a personalized version of the ‘Google Play Store Scraper’. Subsequently, all screenshots were saved in folders divided by results per country. Then all screenshots were categorized per country by using the following categories: ‘general photo/video editor’ (enabling users to add filters or to edit videos), ‘adding features’ (such as stickers), ‘buy/appointment’ (including screenshots which would encourage users to buy certain beauty products or make a beauty appointment at a specific beauty salon), ‘game screenshots’ (showing screenshots of games in relation to beauty), ‘multiple’ (referring to screenshots showing several features facilitated by the application), ‘hair screenshots’ (showing screenshots referring to users being able to edit one’s hair), ‘body screenshots’ (enabling users to change body parts), ‘face screenshots’ (including all face modification options provided by the applications) and ‘other’ (for all screenshots not belonging to any of the other categories, such as screenshots including collages or pictures without any further explanations). After all screenshots were categorized into one of the groups mentioned above, the face screenshots were divided into even smaller sections. The features these screenshots show were split into: ‘eyes’ (including eye make-up, changing the color of the eyes and changing the size of the eyes), ‘face make up’ (including blushes), ‘mouth’ (including the adjustment of the lip color, the whitening of the teeth or the enlargement of the lips), ‘nose’ (including nose adjustments), ‘face/skin (including the altering of the skin color as well as changing the shape of the face) and ‘other’ (including all screenshots not suiting any of the other categories, such as pictures without a clear explanation in relation to the face modifications). Ultimately all face modifications were assembled into visualizations per country to easily compare the differences and similarities concerning face modifications facilitated by the apps regarding (potential) beauty ideals. Unfortunately the methodology used also has its downsides. For instance, this research only looks at three countries, which means this research only highlights a small portion of Google Play Store locations and applications worldwide. Furthermore, to gather the Hindi and Portuguese search queries Google Translate was used. Although the search queries have been checked through visual results on Google, the legitimateness of these queries cannot be guaranteed. Additionally the research mainly focuses on screenshots, whereas the descriptions of the apps might be more specific.Analysis

While analyzing the apps occurring within the app stores after entering the search queries, it became clear that most apps concerning beautification were targeted at women regardless of the country the Google Play Store was located in. For instance, many icons contained either the face of a woman, pink and purple color tones, make up items or a combination of all three. Although these icons may already give an impression of what the applications execute, this research mainly focuses on the screenshots connected to the apps, more specifically the screenshots concerning face modification. Therefore all screenshots concerning face modifications were analyzed more thoroughly after all screenshots had been categorized. While analyzing screenshots concerning the altering of the face, it became clear that, disregarding the country nor the search query used, the screenshots offered face modifications for each part of the face as well as for each feature of the face. For instance, in all countries and for all search queries, face modifications were offered to change skin tones, the eyes or the mouth. Furthermore, the screenshots offered possibilities to alter features of the face, for example by changing the shape of the chin or the cheeks. Yet, the altering of one part of the face was barely represented in the features of the apps represented through the screenshots: the act of editing the nose. The only screenshot including the adjustment to the nose, contained other features as well as seen in figure 1. Figure 1: The only screenshot displaying a feature regarding the altering of the nose.

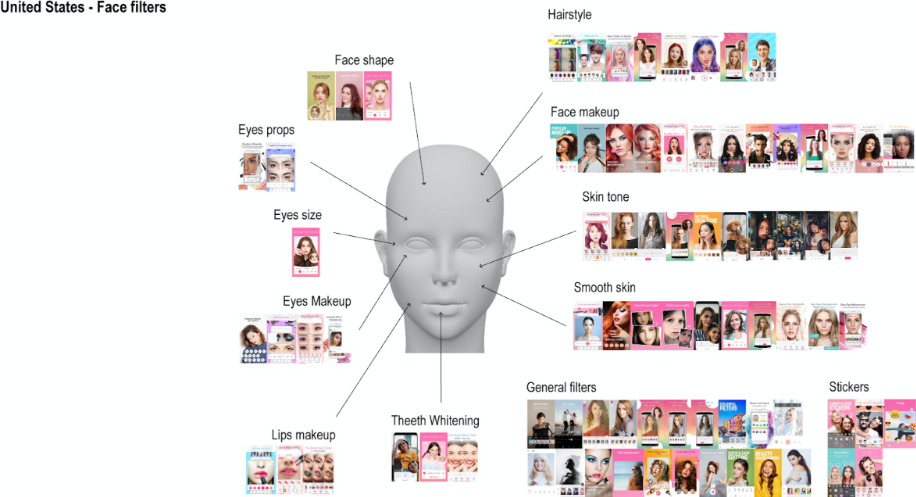

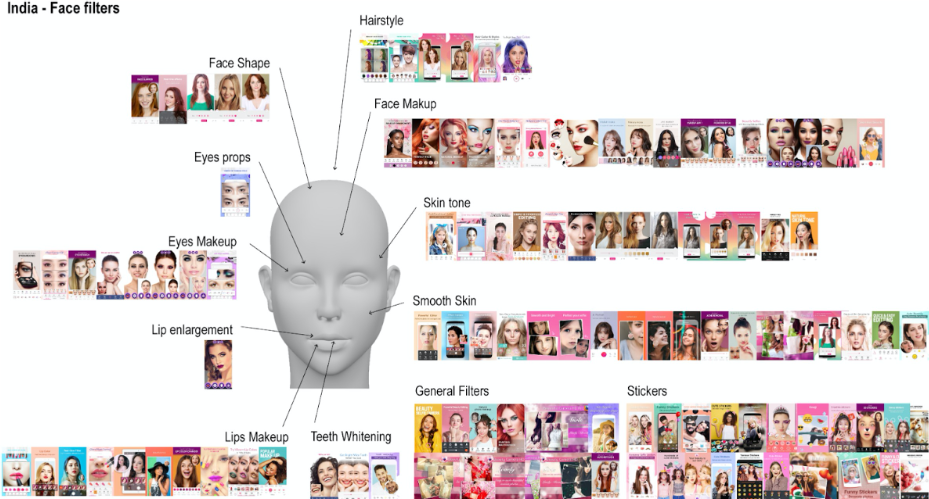

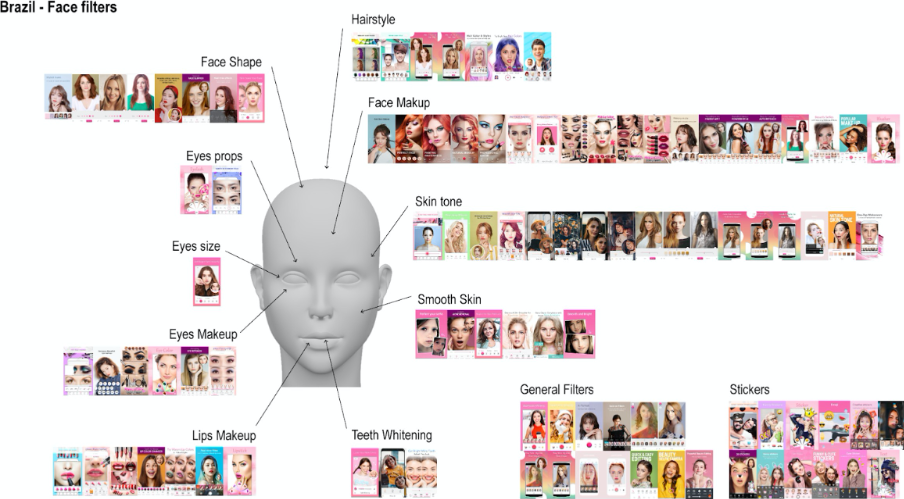

However, after putting all categories referring to face modifications together in a visualization per country, the similarities and differences concerning app features in relation to beauty ideals became clearly visible. For instance, it becomes clear that apps offering features to change someone’s skin tones are way more popular in India and in Brazil in comparison to the United States. This finding could relate to the act of skin bleaching which is referred to earlier in this research. The act of skin bleaching refers to individuals changing the tone of their skin to fit preferred social norms concerning beauty in relation to skin color (Craddock 287). Additionally, altering the shape of the face is also more featured in apps offered in Brazil and India in comparison to the United States. Furthermore, make up features as well as creating a smooth skin seem to be popular in all countries, as seen in figure 2, figure 3 and figure 4.

Figure 1: The only screenshot displaying a feature regarding the altering of the nose.

However, after putting all categories referring to face modifications together in a visualization per country, the similarities and differences concerning app features in relation to beauty ideals became clearly visible. For instance, it becomes clear that apps offering features to change someone’s skin tones are way more popular in India and in Brazil in comparison to the United States. This finding could relate to the act of skin bleaching which is referred to earlier in this research. The act of skin bleaching refers to individuals changing the tone of their skin to fit preferred social norms concerning beauty in relation to skin color (Craddock 287). Additionally, altering the shape of the face is also more featured in apps offered in Brazil and India in comparison to the United States. Furthermore, make up features as well as creating a smooth skin seem to be popular in all countries, as seen in figure 2, figure 3 and figure 4.

Figure 2: All categories concerning face modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of the United States.

Figure 2: All categories concerning face modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of the United States.

Figure 3: All categories concerning face modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of India.

Figure 3: All categories concerning face modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of India.

Figure 4: All categories concerning face modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of Brazil.

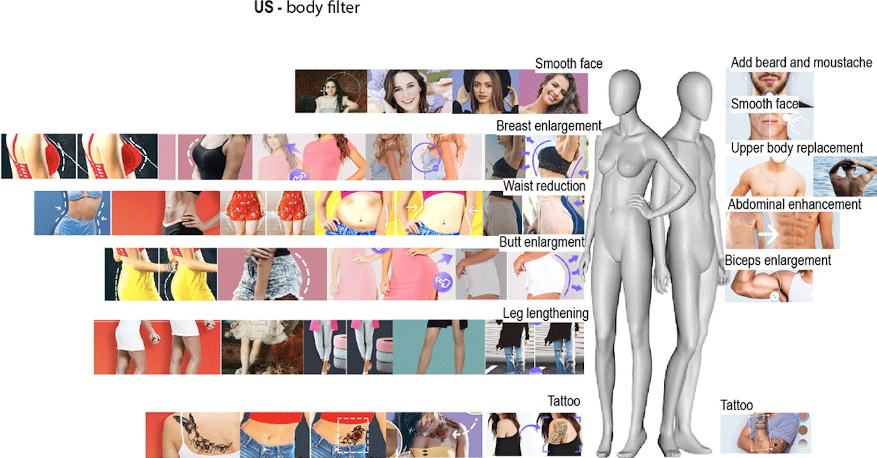

Although this research focused on face modifications only, colleagues Gabriele Colombo and Carlo de Gaetano did a similar research. However, instead of focusing on the face Colombo and de Gaetano paid attention to body modifications. Colombo and de Gaetano searched for ‘Body filter’ in various languages through Google Play Stores located in different countries. When comparing their findings of the United States, India and Brazil to the findings of this research, it turns out there are overlapping results.

For instance, these apps focus dominantly on women as well, which becomes clear when looking at the amount of body modifications focused on the female body in comparison to the number of body modifications concerning male bodies. Furthermore, again socially determined beauty ideals show through when it comes to altering the body. For example, users can digitally tighten the waist of female bodies, enlarge their breasts or bums or make the bodies appear longer. Figure 5 is one of the screenshots which shows this phenomenon. The image states: ‘Be tall like a model’, while figure 6 indirectly refers to a smaller waist as a ‘sexy waist’.

Whereas the features concerning female bodies tend to focus on making the bodies appear taller and smaller, features regarding male bodies offer possibilities to make the bodies appear more masculine, for example by adding muscles or facial hair. Remarkably, India seems to focus more on male users when it comes to altering body appearance digitally in comparison to the United States and Brazil, as seen in figure 7, figure 8 and figure 9.

Figure 4: All categories concerning face modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of Brazil.

Although this research focused on face modifications only, colleagues Gabriele Colombo and Carlo de Gaetano did a similar research. However, instead of focusing on the face Colombo and de Gaetano paid attention to body modifications. Colombo and de Gaetano searched for ‘Body filter’ in various languages through Google Play Stores located in different countries. When comparing their findings of the United States, India and Brazil to the findings of this research, it turns out there are overlapping results.

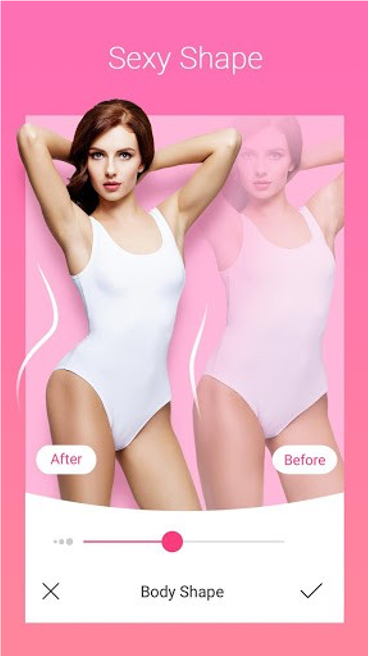

For instance, these apps focus dominantly on women as well, which becomes clear when looking at the amount of body modifications focused on the female body in comparison to the number of body modifications concerning male bodies. Furthermore, again socially determined beauty ideals show through when it comes to altering the body. For example, users can digitally tighten the waist of female bodies, enlarge their breasts or bums or make the bodies appear longer. Figure 5 is one of the screenshots which shows this phenomenon. The image states: ‘Be tall like a model’, while figure 6 indirectly refers to a smaller waist as a ‘sexy waist’.

Whereas the features concerning female bodies tend to focus on making the bodies appear taller and smaller, features regarding male bodies offer possibilities to make the bodies appear more masculine, for example by adding muscles or facial hair. Remarkably, India seems to focus more on male users when it comes to altering body appearance digitally in comparison to the United States and Brazil, as seen in figure 7, figure 8 and figure 9.

Figure 5: a feature offering users the ability to appear as ‘tall as a model’.

Figure 5: a feature offering users the ability to appear as ‘tall as a model’.

Figure 6: this screenshot indirectly refers to a smaller waste as a ‘sexy waste’.

Figure 6: this screenshot indirectly refers to a smaller waste as a ‘sexy waste’.

Figure 7: All categories concerning body modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of the United States.

Figure 7: All categories concerning body modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of the United States.

Figure 8: All categories concerning body modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of India.

Figure 8: All categories concerning body modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of India.

Figure 9: All categories concerning body modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of Brazil.

Whereas Furtado mentions things as not being as they are sold, which could also relate to today’s world of picture altering, Furtado also refers to the beauty of uniqueness of all individuals in the same song. However, when relating those lyrics to this research, it seems as if applications regarding face modifications tend to offer users options to step away from their uniqueness and alter their pictures to socially determined beauty ideals. For instance by creating a smooth skin, editing their skin to socially preferred skin tones, as well as creating a new look by using makeup tools. However, the editing of pictures could also relate to generating more likes on social media platforms, despite the consequences of users their selfimage.

Figure 9: All categories concerning body modifications originated from applications offered within the Google Play Store of Brazil.

Whereas Furtado mentions things as not being as they are sold, which could also relate to today’s world of picture altering, Furtado also refers to the beauty of uniqueness of all individuals in the same song. However, when relating those lyrics to this research, it seems as if applications regarding face modifications tend to offer users options to step away from their uniqueness and alter their pictures to socially determined beauty ideals. For instance by creating a smooth skin, editing their skin to socially preferred skin tones, as well as creating a new look by using makeup tools. However, the editing of pictures could also relate to generating more likes on social media platforms, despite the consequences of users their selfimage.

Discussion

The information that is gathered as the result of the inquiry and the analyses visualizes some important differences and similarities in beautification apps in the Google Play Store of Brazil, India and the United States. While the Google Play Store seems to mainly target female users, an exception can be made for India when it comes to body altering. This exception could mean that in India there is more pressure for men to look muscular by society, as showed through the screenshot collected, or that it is more normalized for man to alter their body in editing apps. It can also be a part of a far larger undiscovered phenomenon. Mobile apps make it easier for people to modify and alter their skin color. Users can experiment and change their skin complexion in beauty editing apps. In India and Brazil skin color alteration seem more prominent than in the United States. As Dieter et al. explained, the interface of apps is designed in such a way that the expectations of their users are integrated in the app design (4). This raises new questions regarding the influence mobile apps have on skin color dissatisfaction and if they promote certain beauty ideals to their users. Which consequently can lead to skin whitening and tanning practices. A suggestion can be made to further research the issue of what transpires after users upload their pictures in the Beautification editing apps. What will these apps do with the data and where do the photos end up.Conclusion

To answer the research question: ‘What are the differences and similarities of digital face modifications proposed by beautification apps in the Google Play Store of Brazil, India and the United States?’, screenshots have been gathered from the Google Play Store in the United States, India and Brazil. Conclusively, the similarities of the presented screenshots in the Google Play Store cross-culturally demonstrate face alteration for the whole face. This includes amongst other things, the alteration of skin color, mouth and eyes. Although beauty editing apps offer many other face alteration options, like nose modification, this is not represented in the screenshots of the apps cross-culturally. However, skin smoothening on the other hand is favorable in all countries. Throughout the analyses many differences were discovered between India, Brazil and the United States. An interesting observation is that in India and Brazil apps offer a greater deal of skin color alteration and skin shape modification than in the United States. This can correlate with the skin lightening practices in India which are very popular. These findings could clarify the relation between social beauty ideals and features offered through beautification apps. With the support of colleagues Colombo and de Gaetano, who focused their research on body modification in the Google Play store in India, Brazil and the United States more findings on beautification apps could be gathered. For instance, how applications offered female users to appear taller and slimmer and for male users to become more masculine within their photos. Noticeably, face and body modification app target female users much more than their male counterparts. In India the focus on male body modification seems to be much larger than in Brazil and the United States. India’s Google Play Store promotes a muscular man with facial hair. The presentation of body modification concerning either tall and slim bodies for 15 women or masculine bodies for men could relate to social beauty ideals displayed through features of beautification apps as well, which relates to the relation of face modifications and social beauty ideals. Therefore it can be concluded that even though apps offer the same face modification features cross-culturally, beauty ideals per country are indeed represented in the apps and their features.References

“Beautification”. Cambridge Dictionary. Accessed 22 January 2020. < https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/beautification>; “Google Play Store Scraper”. GitHub. Accessed 15 January 202. < https://github.com/facundoolano/google-play-scraper>; “Link Ripper”. Digital Methods. Accessed 15 January 2020. < https://tools.digitalmethods.net/beta/linkRipper/>; Briskman, Jonathan. “Top Countries Worldwide for Q2 2019 by App Downloads.” Sensor Tower. 5 Augustus 2019. Accessed 22 January 2020. < https://sensortower.com/blog/top-countries-app-downloads-q2-2019-data-digest>; Craddock, Nadia. “Colour me beautiful: Examning the shades related to global skin tone ideals.” Journal of Aesthetic Nursing. 5.6 (2016): 287-289 Daniel, A. “English in India”. Adaniel. Accessed 22 January 2020. <http://adaniel.tripod.com/Languages3.htm> Dieter M, Gerlitz C, Helmond A, et al. (2019) Multi-Situated App Studies: Methods and Propositions. Social Media + Society 5(2): 1–15. DOI: 10.1177/2056305119846486. Furtado, Nelly. “Try”. Genius. Accessed 22 January 2020. < https://genius.com/Nelly-furtado- try-lyrics> Guest, Ella. “Photo editing: enhancing social media images to reflect appearance ideals.” Journal of Aesthetic Nursing. 5 (9) (2016): 444-446 Klenk, Saskia, Doreen Reifegerste, and Rebecca Renatus. "Gender differences in gratifications from fitness app use and implications for health interventions." Mobile Media & Communication 5.2 (2017): 178-193. Pariona, Amber. “What Languages Are Spoken In Brazil?”. World Atlas. 7 August 2018. Accessed 22 January 202. <https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-languages-are- spoken-in-brazil.html> Rajanala, Susruthi, Mayra BC Maymone, and Neelam A. Vashi. "Selfies—living in the era of filtered photographs." JAMA facial plastic surgery 20.6 (2018): 443-444. Szczepanski, Kallie. “The British Raj in India.” Thought Co. 4 January 2020. Accessed 22 January 2020. < https://www.thoughtco.com/the-british-raj-in-india-195275>Edit | Attach | Print version | History: r1 | Backlinks | View wiki text | Edit wiki text | More topic actions

Topic revision: r1 - 31 Jan 2020, AnneHelmond

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback