Exploring political narratives around the 2024 European Elections

Team Members

- Fabio Daniele

- Lorenzo Vernetti

- Energy Ng

- Furkan Dabaniyasti

- Sara R. de Andrade Silva

- Heidi Ippolito

- Alice Picco

- Esmée Colbourne

- Mark Mets

- Ángeles Briones

Links

Summary of Key Findings

Our project adopts a quantitative approach to investigating narratives by integrating Narrative Intelligence methodologies and using Large Language Models (LLMs) to explore and systematically analyse narratives. We applied this methodology to a dataset of approximately 50k news articles and 6k Telegram messages from the month preceding the European Elections, focusing on political topics sourced from newspapers and news agencies in Italy, Germany, Netherlands, and Romania, as well as Telegram channels linked to Kremlin propaganda. The data was explored using narrative analysis and different investigation and visualisation techniques to understand how narratives around the EU election were constructed. Contextualising characters and themes into their recurring motifs gave us insight into the meanings people ascribe to political leaders and events, the performativity behind political values, and the general hopes and fears that drive people to vote in elections. In the future, this data could be placed in conversation with research into fake news to understand disinformation and misinformation impact or to cross-verify where people are getting their news and political commentary from.

Introduction

Within the context of Information Disorders (i.e., mis-, mal-, and disinformation), much attention has been brought in recent years towards the concept of narratives, as in the framework that conveys a particular understanding or interpretation of an event expressed through a story. Virtually all organizations involved in fact-checking or counter-disinformation have shifted their activity towards a narrative-centered approach to offer more comprehensive debunking to their external audience and improve detection and pre-bunking capabilities within their internal operations. The use of narratives has shown promising results, but some limitations restrict us from harnessing the full benefit of this approach. One significant limitation is the intangible nature of narratives, often due to the lack of a standardized definition, which relegates them to a qualitative role. While they offer a valuable method for analyzing the ever-increasing amount of information on the internet, they still heavily rely on domain-specific knowledge from human researchers. This dependency interferes with our capacity for automation and introduces the potential for biased assessments. A quantitative dimension must be added to bridge these gaps and provide a more objective and scalable approach. One way to achieve this result is to introduce elements of Narrative Intelligence, a methodology that intersects with OSINT processes and brings a data-first approach to exploring narratives. In Narrative Intelligence, a narrative is defined by a set of fundamental components (characters, setting, plot, conflict, themes, message, point of view) and enriched by contextual metadata (sentiment score, keywords, disambiguated entities) to provide a predictable, consistent, and machine-readable structure to the data.While Narrative Intelligence was traditionally confined to conventional Machine Learning techniques, it now stands to gain significantly from the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs). Due to the wide availability of pre-trained models, LLMs offer unprecedented opportunities for extracting narratives from massive amounts of data at a scale and a fraction of the cost.

In this project, we will explore possible visualisation methods for narratives sourced and extracted by LLMs, while at the same time validating the usefulness of data obtained by applying the Narrative Intelligence methodology.

Initial Data Sets

The original dataset was collected by Sustainable Cooperation for Peace & Security (SCPS), a European NGO focused on Peacebuilding and Cyber Peacebuilding activities.

Data was collected from:

-

News Articles: 50k articles from Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania, and Georgia, focusing on political topics in the 30 days before the 2024 European Elections. The data was acquired by using NewsCatcher ’s API and the scraping of selected RSS feed.

-

Telegram Channels: 6k messages acquired by manual scraping of 30 Telegram channels linked to Kremlin propaganda and Russian military bloggers.

After the acquisition, a series of transformations were performed on the data in order to extract the narratives:

-

Removal of any HTML or markup tag to ensure the content featured only pure text.

-

Normalisation and translation of the texts into English using DeepL to ensure optimal performance of the NLP and LLM transformations in later stages.

-

Extraction of disambiguated Named Entities from the text by using Spacy.

-

Sentiment Analysis using Google Cloud Natural Language.

- Keyword Extraction via RAKE.

-

Narrative Extraction from text using gpt-3-5-turbo (OpenAI) and claude-3-opus (Anthropic) models by instructing LLMs to perform data extraction following a predetermined schema (sample of the narrative schema available here).

The two datasets resulting from this transformation pipeline were consolidated in JSONL format and served as the foundation for the execution of this project. Each narrative contained in the dataset followed the same data schema, to ensure consistency. The schema of a narrative is comprised of the following fields:

-

Characters: these are the agents within the narrative, typically people, organisations, nations, or even inanimate objects anthropomorphised for the sake of the story.

-

Setting: time and place where the story takes place, providing context for the story to unfold.

-

Plot: the sequence of events that make up the story's structure; it unfolds with a beginning, middle, and end, guiding the reader through the narrative's progression.

-

Conflict: the point of divergence, or problem, from which the story develops; narratives are likely to inherit the authority of true belief and preclude alternative ways of thinking about political or strategic narratives.

-

Themes: the subjects explicitly or inherently mentioned in the story, acting as lexical ties between messages.

-

Message: the moral of the story, or persuasion points, directed towards the reader; this incorporates a notion of the goals, ideological bias held by characters in a narrative and the various means they have to accomplish these goals.

-

Point of view: the point of view of the narrator (first-person, second-person, third-person), which might incorporate invisible or impalpable biases.

Objective: To validate the efficacy of Narrative Intelligence methodologies in extracting and analysing narratives from news articles and Telegram channels.

-

Are there patterns that can be observed within the dataset(s)?

-

Are there patterns that can be correlated with external sources, world events, or other significant circumstances?

-

How could the narratives, or some of their components, be visualised?

-

How could similar narratives be identified and clustered?

Methodology

The research was separated into two parts:

-

First, an investigation of the data to identify patterns among its components, possible clusterisation of similar narratives, and exploring visualisation methods for narratives and their components;

-

Second, an exploration of how AI-powered image generation might provide an image-based system for the clustering of similar narratives.

Part One

The web dataset was categorized into several different narrative tools. We then used different visualization techniques to explore what these data could mean.

The data was visualized in the following ways:

-

Characters: people, places, and things

-

Relating biassed sources to characters

-

Scatterplot of source bias and credibility per character

-

-

Setting

-

Plot: beginning, middle, and end

-

Conflict

-

Themes: 30 by occurence

-

Italy, Germany, Netherlands, and Romania

-

Line Charts

-

-

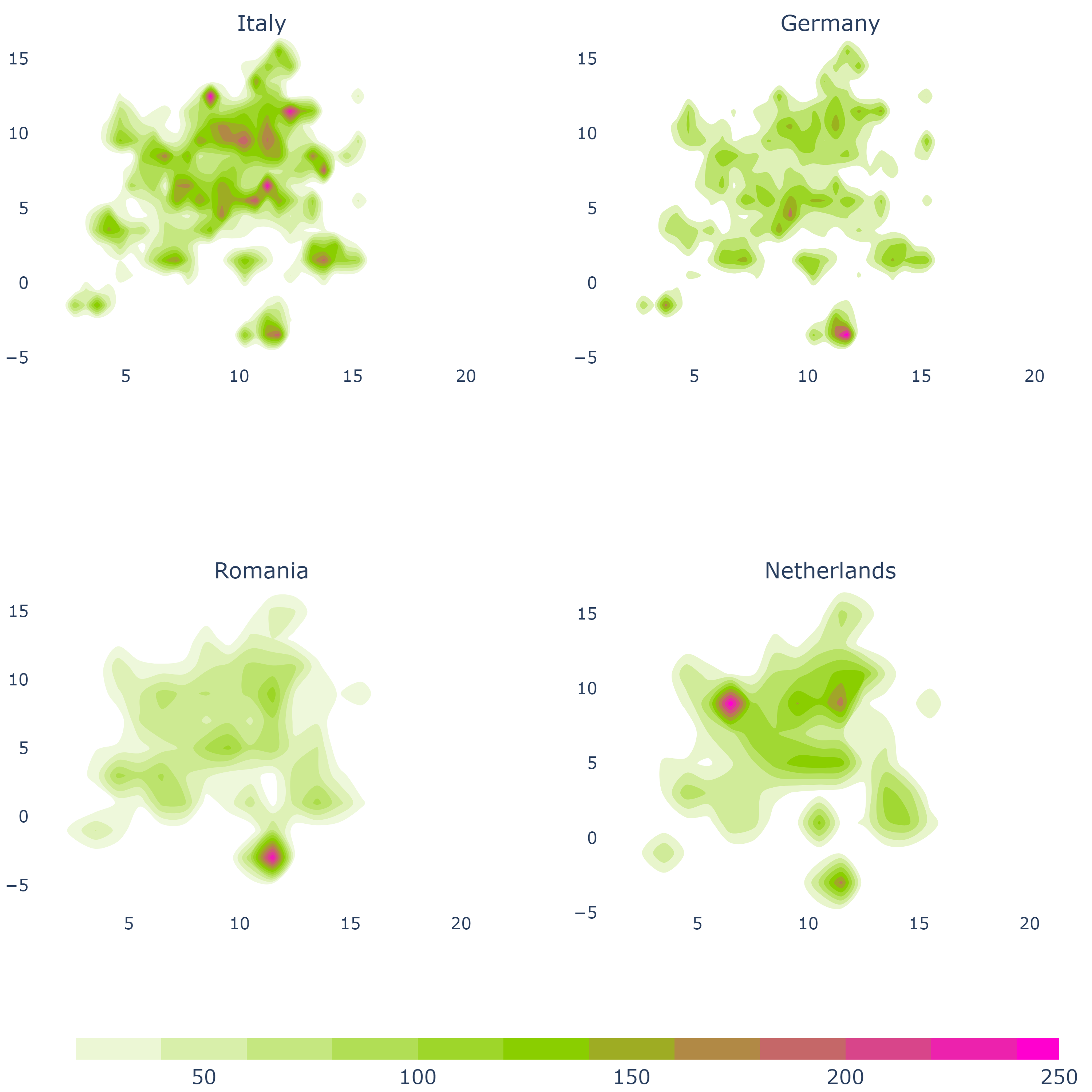

Message: Embeddings with Sentence Transformer LLM

-

Reducing to 2 dimensions with UMAP

-

Manually identifying messages on scatterplot

-

Density plots per country

-

Part Two

PHOTO ROMANCE EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Part two of the group’s methodologies was more experimental, using generative AI. The experiment had two separate elements, the first was attempting to depict main characters per country and the second section was to pull in and visualize multiple perspectives on a theme. In Depicting Main Characters Per Country, Generative AI was used to visualize the narrative around the characters, we used web articles about Meloni, Geerts, and Scholz and created images that represent the narrative within the text.

The second experiment was analyzing the themes and how they support multiple political perspectives. To see different thematic narratives DEMOCRACY was selected as a core theme and one random article per day about that theme within the selected countries was selected. This web article data was then used to visualise through Stable Diffusion.

Example Prompt

Original Text:

Struggle against terrorism, hatred, and violence in the face of threats to freedom and democracy.

Massacre of Brescia followed by plagues, intimidation, neo-fascist attacks. Response of Brescian civil society against threats and violence, black terrorism raising criminal action. Rejecting and isolating preachers of hatred, living the principles and values of the Constitution, working for unity and peace”

Prompt:

Subject: President of the Republic Sergio Mattarella, Brescian civil society, attackers, preachers of hatred, operators of mystification,sowers of discord,citizens

Medium: PHOTO-REALISTIC

Environment: 50 years ago, Brescia, Piazza della Loggia

Mood: very negative about

Terrorism, Unity, Freedom, Democracy, Peace, Justice

Composition: Point of view of President of the Republic, Sergio Mattarella

Findings

Main themes that were associated with more than one country were: climate change, conflict, corruption, and democracy. Preliminary findings of this project point to the idea that issues of public salience span across the European union.

DEPICTING MAIN CHARACTERS PER COUNTRY

Within the sample visualization, there was a notable AI art-style towards cartoonization of political figures. Different characters had different themes and interesting quirks integrated into each visualization set.

Geert Wilders

-

Surrounded by other characters in his representation

-

More dynamic expressions

-

Less ‘real’ most cartoon of the set

-

Most ‘real’ and neutral

-

Muted colours

Giorgia Meloni

-

Surrounded by faceless crowd

-

Not shown with other women

-

Only one presented in a more intimate, private environment

Visualization

- All countries chosen had a combination of hyper real and cartoon imagery

- Combo of black and white a colour representations

- Individual character in each - strong ties to one or two political figures

Germany

Images show themes of war, voting, international relations

Romania

Trump, war

Italy

European flags, Migration, war, Giorgia Meloni

Findings

Our project adopts a quantitative approach to investigating narratives by integrating Narrative Intelligence methodologies and the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) to explore and systematically analyze narratives. We applied this methodology to a dataset of approximately 50k news articles and 6k Telegram messages from the month preceding the European Elections, focusing on political topics sourced from newspapers and news agencies in Italy, Germany, Netherlands, and Romania, as well as Telegram channels linked to Kremlin propaganda. The data was explored using narrative analysis and different investigation and visualization techniques, in an attempt to understand how narratives around the EU election were constructed. Contextualising characters and themes into their recurring motifs gave us insight into the meanings people ascribe to political leaders and events, the performativity behind political values, as well as general hopes and fears that drive people to vote in elections. In the future, this data could be placed in conversation with research into fake news to understand fake news impact, or to cross verify where people are getting their news and political commentary from.Discussion

Our findings represent the beginning of greater research aimed at enhancing the Narrative Intelligence approach, which focuses on studying information disorders to provide new investigative tools for researchers and cyber responders. Our work on understanding and visualising narratives surrounding the 2024 European Elections is the first attempt at setting a new data-driven framework for conducting investigations into narratives, testing a quantitative approach to narrative analysis, and pinpointing a more exact definition of the terminology. This modelisation of narratives attempted to establish an opinionated modelisation for future cross-integration of datasets related to misinformation, malinformation, and disinformation. Understanding this data set entails a comprehensive exploration of its biases and a rigorous discussion of its validity. The data is a complex interplay of many intersectional identities, reflecting the diverse demographics that situate the individual message producers within their respective countries’ political climates. This, in turn, contributes to the mosaic that shapes the concepts of EU and Fortress Europe. The method of data collection significantly influenced our research questions and results. We have produced visualisations that enable us to discern the relationships between different narratives and their evolution over time.This project and data science as a whole can be approached from a play standpoint. This analysis builds upon our approach to navigating the complexities of the original unruly data set, which presented challenges due to its size and the need for more normalisation within specific components of the narratives, namely characters and themes. We experimented with the data via different cleaning methods and then through many visualisations. Our goal was ultimately to make the data more intuitive and clean, testing different methods to cut through the noise and quickly isolate clusters of narratives that could be subject to further processing by means of computation or data visualisation.

The data was, in part, explored using narrative analysis. This was done to understand how narratives around the 2024 European Elections were constructed, particularly which characters engaged with which themes. Contextualising these characters into their recurring motifs gives us insight into the meanings people ascribe to political leaders and events, the performativity behind political values, and the general hopes and fears that drive people to vote in elections. It also helps provide examples for normative right-wing vs. left-wing politics. A brief critique of the narrative framework is that it can lead to narrative fatigue, and putting people’s data into these frameworks might be reductive. However, it still has significant value. In particular, narrative methods are effective for understanding the past and linking actions to their implications. Although this project mainly focused on thematic analysis, the research could be expanded to trace the change of political thought over the sample period, not just theme occurrence in Germany. As researchers, we were not looking for the facts or even the objectivity of the data. Ultimately, due to the abovementioned challenges in processing and approaching the datasets, much of our attention has been spent on finding the best strategies to approach the data. In the future, this data could be placed in conversation with research into fake news to understand its impact or to cross-verify where people get their news and political commentary from.Conclusions

This project has demonstrated the potential of integrating Narrative Intelligence methodologies with Large Language Models (LLMs) to systematically analyze and understand political narratives surrounding the 2024 European Elections. By employing a quantitative approach, we have been able to dissect and visualize the complex web of narratives present in a substantial dataset of news articles and Telegram messages. Our analysis has highlighted the recurring motifs and themes that shape public perception of political leaders and events, providing insights into the performative nature of political values and the underlying hopes and fears that influence voter behavior.

The findings underscore the importance of narratives in the context of information disorders, particularly in the realm of mis-, mal-, and disinformation. The project's approach offers a scalable and objective framework for narrative analysis, which could be instrumental in enhancing fact-checking and counter-disinformation efforts. However, the reliance on narrative frameworks also poses challenges, such as potential narrative fatigue and the reductive nature of categorizing complex human data into predefined schemas.

Despite these challenges, narrative inquiry remains a valuable tool for understanding the human condition and the evolution of political thought. The project's methodologies and findings lay the groundwork for future research, particularly in exploring the intersection of narratives with fake news and the sources of political commentary. By refining and expanding upon this research, we can continue to develop innovative tools and strategies for addressing the challenges posed by information disorders in the digital age.

References

- Barkhuizen, Gary Patrick. The Handbook of Narrative Analysis. Edited by Anna De Fina and Alexandra Georgakopoulou, 1st ed., Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

- Ruston S. Narrative & Strategic Communications. In: Russia's Footprint in the Nordic-Baltic Information Environment 2019/2020. NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence; 2020:6-16.

- Labov W, Waletzky J. Narrative Analysis: Oral Versions of Personal Experience. J Narrat Life Hist. 1967;7(1-4):3-38.

- Van Dijk TA. Some Aspects of Text Grammars: A Study in Theoretical Linguistics and Poetics. The Hague: Mouton; 1972.

- Foret, Francois, and Noemi Trino. “The ‘European Way of Life’, a New Narrative for the EU? Institutions’ vs Citizens’ View.” European Politics and Society (Abingdon, England), vol. 24, no. 3, 2023, pp. 336–53, https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2021.2020482.

- Labov W, Waletzky J. Narrative analysis: oral versions of personal experience. Journal of Narrative and Life History. 1997;7(1-4):3-38. doi:10.1075/jnlh.7.02nar

- Fog K, Budtz C, Yakaboylu B, Stevens T. Storytelling: Branding in practice.; 2005. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB05945697.

- Chatman S. Towards a theory of narrative. New Literary History. 1975;6(2):295. doi:10.2307/468421

- Thorndyke PW. Cognitive structures in comprehension and memory of narrative discourse. Cognitive Psychology. 1977;9(1):77-110. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(77)90005-6

- Mastroianni, R. (2019). Fake news, free speech and democracy: A (bad) lesson from Italy. Sw. J. Int'l L., 25, 42.

- Bradshaw, S., Campbell-Smith, U., Henle, A., Perini, A., Shalev, S., Bailey, H., & Howard, P. N. (2021). Country case studies industrialized disinformation: 2020 global inventory of organized social media manipulation. Oxford Internet Institute.

- Dupuis, M. J., & Williams, A. (2019, August). The spread of disinformation on the web: An examination of memes on social networking. In 2019 IEEE SmartWorld, Ubiquitous Intelligence & Computing, Advanced & Trusted Computing, Scalable Computing & Communications, Cloud & Big Data Computing, Internet of People and Smart City Innovation

- EuDisinfoLab. The role of “media” in producing and spreading disinformation campaigns. 2021. https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/the-role-of-media-in-producing-and-spreading-disinformation-campaigns

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback