Syrian hashtags and their visual language as reactions to events - a comparison between the English and Arab language spaces on Twitter (with a short trip to Facebook..)

Team Members

Marloes Geboers (facilitator)Andra Irina Cristina Ene,

Benjamin Philip Blackwell,

Carlo De Gaetano,

Chad Van De Wiele,

Chiara Piva,

Katrine Meldgaard Kjaer,

Nermin Elsherif,

Petra Audyova,

Tayfun Kasapoğlu

Contents

Summary of Key Findings

Hashtags create ad hoc publics that are rendered through shared opinions, political views and affect. This particular project concerned itself with the communicative practices of hashtag publics (Bruns & Burgess, 2015) on Twitter relating to the Syrian war. These publics communicate (often visually) through calling for action, commemorating, conveying solidarity or through communicating a political or critical stance. The ultimate goal is to gain insight in Twitter as an affective space by zooming in on visual content as containing affect. That is, as 'binding'/rendering publics affectively. The studied time span contains two offline events that trigger, at least in the English language space, user activity significantly: the chemical attacks on Douma, Syria on April 7, 2018 and the air strikes reponse of France, UK and the US on April 14. In this project we were able to explore a data set that gave us the opportunity to distinguish between the Arab and English language spaces on Twitter. The specific queries can be found in the initial data sets section (2).

It seems that the Arab language space on Twitter is much more localized, both in the content of hashtags and the images that are prominent in these hashtags spaces. With dominant hashtags such as the actual place of the chemical attacks of April 7 (#Douma and #Eastern Ghouta) and explicit images of victims that were most frequently tweeted media, the visual language is rather different than that of the English space, where hashtags such as #Russia and #Trump, dominate the arena, in the second event we see #syriastrikes as the dominant hashtags in the English space. The imagery here is connecting to the textual content of the hashtags, see treemaps in the Findings section.

We were rather surprised by the late 'take off' of the common solidarity hashtag #prayforsyria. It seems to be taken up only during and after the airstrikes of April 14, whereas the chemical attacks on April 7 do not trigger this hashtag significantly (it is present, but small). It pops up rather big as of April 14 and seems to connect to a wide range of other hashtags (see co-hashtag network graph in Findings section). This is even more surprising when we take into account the dominant position of this particular hashtag during the attacks on Khan Shaykhun on April 7, 2017. This attack is similar in several aspects but a year earlier this solidarity hashtag was revived much quicker than in 2018. Please note that we did not exclude other solidarity hashtags from our analysis, we chose to be inclusive and found that just one solidarity hashtag is significantly present and only in an event that involves airstrikes initiated by the west (US, UK and France).

1. Introduction

Introduce the subject matter, and why it is compelling / significant. The digital realm is a unique space for emotional discourses. Oftentimes emotions are socially shared through visual communicative practices. Like many other (social) platforms, Twitter is a place where images incorporate original photographs, edited and re-worked images and otherwise (re)appropriated visuals. The latter includes the use of pre-existing media items, applied in new and unrelated contexts as signifiers of particular emotions, opinions, punch lines, and reactions of users (Highfield & Leaver, 2016). Just as news photographs should be read (Barthes, 1977) these signifiers of particular emotions, opinions and reactions provide us with essential clues on how people emotionally connect with tragedies through social platforms and how tragedies are re-contextualized by users. Such images are typically hashtagged or at least these hashtags provide for a 'way into' the data. Commemorative hashtags such as #PrayForSyria on Twitter serve as examples of “established solidarity symbols” (Collins, 2004). Social sharing forms an integral component of online discourse leading to a digital affect culture: a concept that was recently developed by Döveling, Harju and Sommer (2018). They build on the notion of ‘affective publics’ (Papacharissi, 2014) that are rendered through expressions of shared sentiment. Digital affect cultures come into being when emotional alignment and resonance constructs atmospheres of emotional and cultural belonging (Döveling et al, 2018). As emotions within divergent discourses (such as love, fear, and anger) construct subject positions that are mobilized in digital contexts, a discursive arrangement is engendered that gains traction within online circulation (see also Kuntsman, 2012). By creating and drawing upon other creations, users engage in a visual language of tragedy that is clearly visible on social platforms. In a winter school project of Digital Methods (2018) it was found that user generated and user created illustrations or re-workings of images (oftentimes illustrations) are crowding out the original photographs of victims on the ground (the case study here was the Syrian war) - during the peak time of an event (in this case the chemical attacks on Khan Shaykhun). Important to note is that, although re-working images provides for a way to engage with tragedy, Boudana et al. (2017) and Zelizer (2006) critique such practices of reproduction as leading to a dilution or distortion of meaning. As a large part of re-workings of images and of generic visual expressions of solidarity are illustrations, it is also important to refer to scholars such as Boltanski (1999) who argue that the aestheticization of what we see in the media emotionally and morally insulates viewers from the suffering of others.2. Initial Data Sets

List and describe your data sets. We had at our disposal a dataset which was a subset of a larger DMI-TCAT bin that is, as of January 23, 2018, collecting tweets with the following hashtags and keywords: [Syria] OR [#Syria] OR [Sirya] OR [#Sirya] OR [#Syrianrefugees] OR [#Eastghouta] OR [#Idleb] OR [#assadmustgo] OR [#PrayforSyria] OR [#IranOutofSyria] OR ['Khan Sheikhoun'] OR [#KhanSheikhoun] OR ['Khan Shaykhun']['الغوطة الشرقية'] OR [#إدلب] OR [إدلب] OR [#الغوطة_الشرقية] OR ['اللاجئ السوريون'] OR [سوريا] OR [سوريا#] OR [#خان_شيخون] OR ['خان شيخون']

We subsetted it to a time span of March 25 - April 30, 2018 as this would include a short time span before and after the chemical attacks on Douma, Syria of April 7. The total number of tweets amounts to 7.815.418 tweets.3. Research Questions

Clearly state your research questions and any hypotheses / expectations.-

How is remembering and forgetting (distant) suffering ‘happening’ visually and affectively on Twitter and Facebook?

-

What emotions occur with remembering and forgetting on Twitter and Facebook?

-

Is visual affect on FB and Twitter different in terms of the emotions that visuals communicate, and in terms of longevity of concern?

4. Methodology

Explain your methodology / approach. Due to the size of the dataset we could not export full datasets from TCAT, this can be easily solved by exporting small time spans or taking out random samples. For time's sake we decided to discard the outer time spaces (before and aftermath) and focus on the user activity spikes (see figures 1 and 2).Co-hashtag networks Based on user activity we chose to zoom in on two time spans across two language spaces (7-13 April and 14-21 April). To demarcate languages we decided to untangle the query of the bin and divide it in the English tags and words and the Arab tags and words. This results in four datasets of which we made four co-hashtag networks. See findings section below. After establishing co-occurrence of frequent hashtags we delved into most frequent media using. Two days of significant user activity in each time span, in each language were analyzed (April 9 and 14) for most frequent images (most retweeted). The top 20 images for both days in two languages were visualized in treemaps using Rawgraphs. See findings section below. Facebook We tried to establish a cross-over from this analysis on Twitter to analysis of Arab and English language public pages on Facebook. Therefore we started off with deciding on a page list through querying Google as follows: Site: Facebook Syria

Site: Facebook سوريا The top 5 public pages that Google feeded to us, were then scraped using Netvizz. In the full stats .csv file we used Reactions metrics to establish 'most angry, most sad and most loved' images in a time span of one month (April 2018). As post content on pages often use both languages, especially in large public pages surrounding this issue, we arrived at looking at images that were very much the same, see findings section.

5. Findings

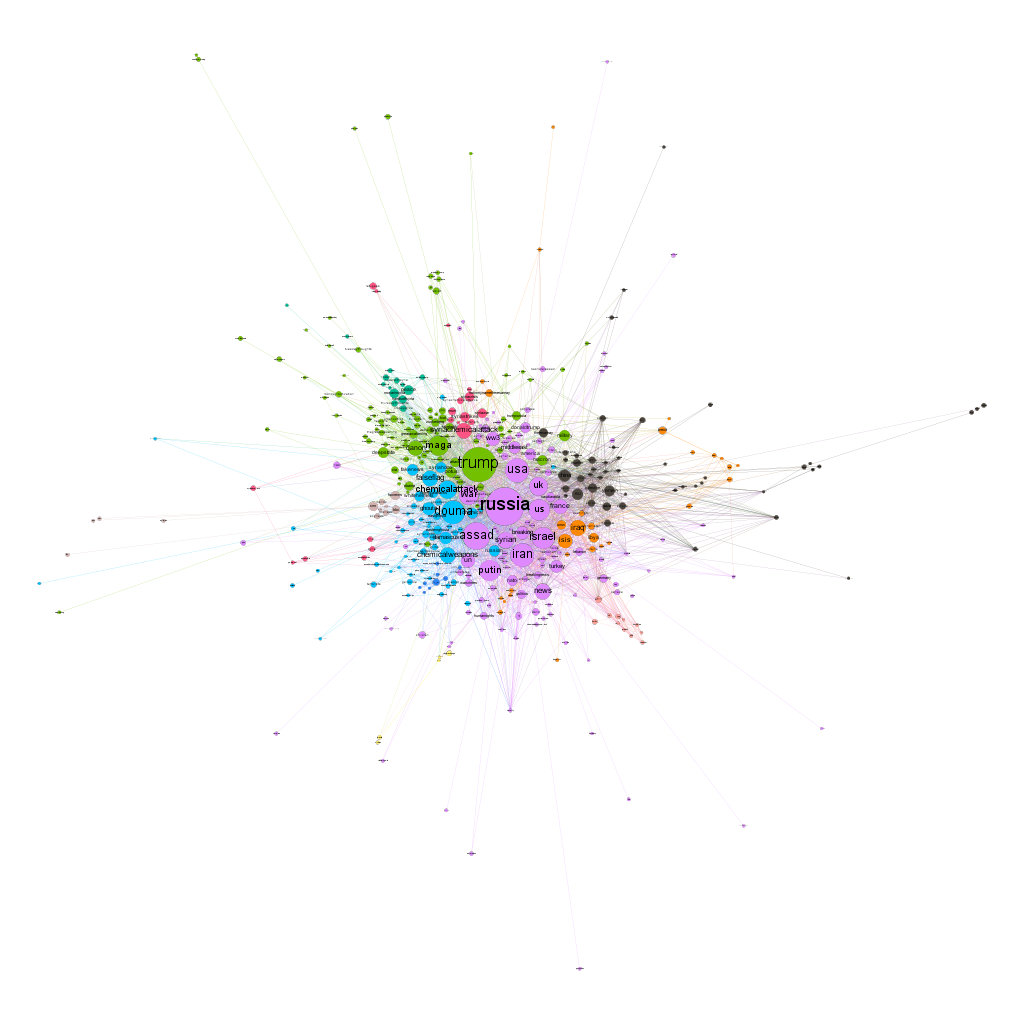

Co-hashtag networks of two periods of spikes in Twitter user activity. These networks were created per language (Arab-English), see their queries in the Data sets section, section 2 of this document. After the removal of peripheral content (e.g., hashtags occurring fewer than 100 times, nodes with fewer than 20 edges, etc.), modularity revealed closely-knit communities of hashtags within each network. Note that both spikes in Twitter activity are triggered by two different events: the chemcial attacks on Douma on April 7, 2018 and the western response to these attacks, which involved air strikes on April 14. Figure 3, 7-13 April, English language.

Figure 3, 7-13 April, English language.

Within the first Western hashtag network, 11 communities of content were revealed, each reflecting distinct patterns of discourse surrounding the chemical attacks on Douma. Networked discussion converged on issues related to offline events in Syria (e.g., #douma, #chemicalattack, etc.), as well as a variety of adjacent political topics. Namely, the nodes ‘russia’ and ‘trump’ had the greatest word frequency within this first cluster, highlighting their prominence in Western Twitter discussion of the Syrian war.

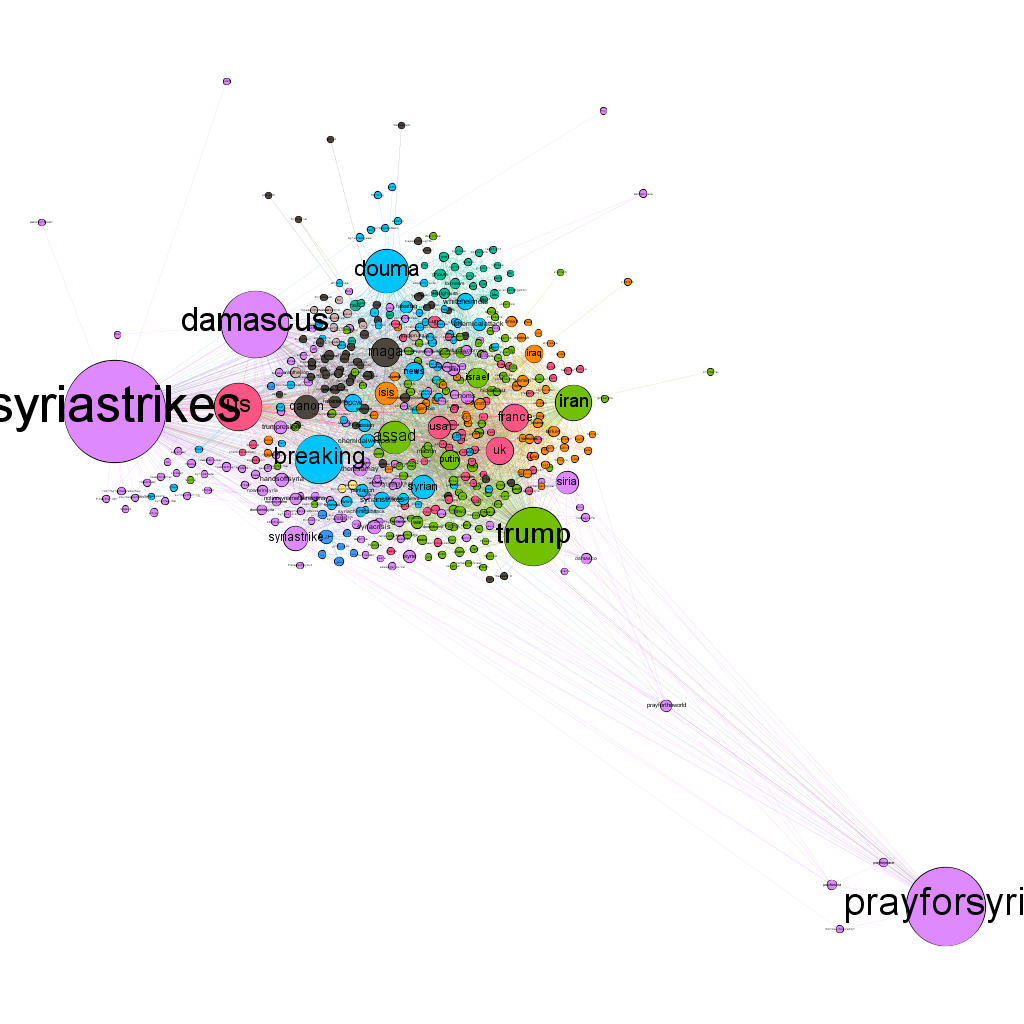

Figure 4. 14-21 April, English language

We then see the solidarity hashtag PrayforSyria taking up significantly, which surprised us, as it remained small during the Douma attacks and only significantly revives with western airstrikes involvement. See also the conclusion section.

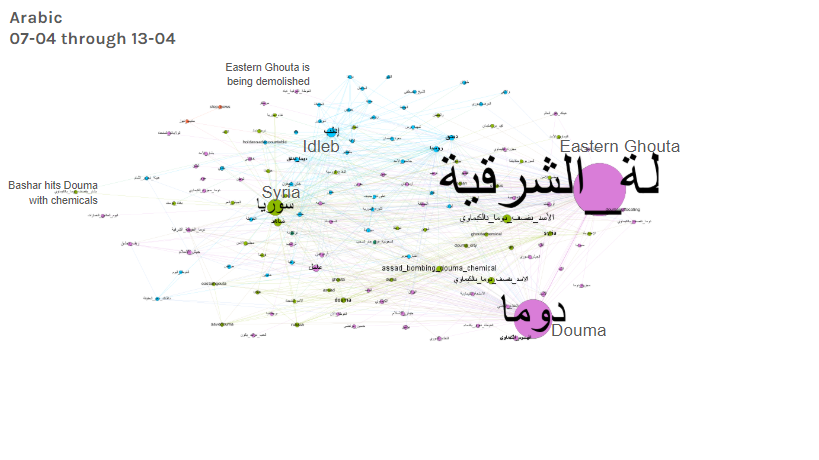

Figure 5.

Most prominent hashtags refer to the places where attacks happened. Localized hashtags are much more dominant as opposed to the Eglish language space.

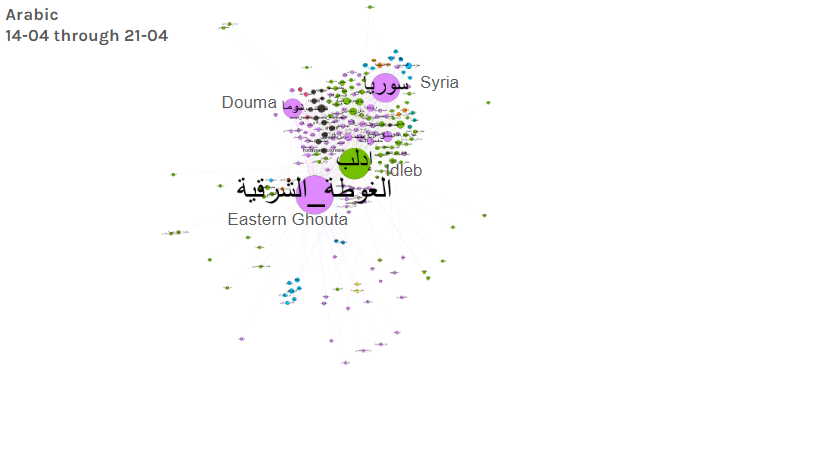

Figure 6.

The most prominent hashtag is دوما which is Douma, appears in purple, surrounded by a group of smaller hashtags like Bahrain, Kuwait, Moscow, England, Trump, etc. The visualisation shows seven modules each containing hashtags of almost the same size.

Visual Treemaps

6. Discussion

Discuss and interpret the implications of your findings and make recommendations for future research and application, be it societal, academic or technical (or some combination). The operationalization of the acts of remembering and forgetting prove to be somewhat challenging. What we are studying when following the 'social lives' and the use of hashtags in times of significant offline events, is actually more related to user concern and the longevity of user concern (or commitment) with a certain event or issue. Taking up user concern and user commitment as our object of study, is drawing from the way in which Rogers (2018) operationalizes user engagement in a digital methods way. Bruns and Burgess (2015) have pointed out how hashtags can have an emphatic function for users, especially evident in the sender’s emotional or other responses. As examples the authors refer to tags such as #sigh, #facepalm etc. However, hashtags and words that refer to emotions or affect provide for a way to study the affective space that hashtags and images that connect to certain hashtags ' inhabit'. In the near future this exploratory work could be a first step into researching affect on Twitter and it's visual substance, by creating, for example, hashtag-word networks and hashtag-image networks. By creating co-occurrence hashtag networks and hashtag-word networks, emotional clusters (eg. between a solidarity hashtag and tags and words such as #angry or #sad or #frightening) one could gain insight in emotions connected to certain affective hashtags. By tracking most resonated images in these clusters we might be able to add another layer to these networks showing samples of resonating images. These should be qualitatively assessed to see their affective content. Through analyzing tweet images that resonated intensely in certain hashtag and emotional words clusters, one could gain insight in the emotionality and the evolving of emotionality over time in particular (solidarity and affective) hashtag publics.7. Conclusions

It seems that the Arab language space on Twitter is much more localized, both in the content of hashtags and the images that are prominent in these hashtags spaces. With dominant hashtags such as the actual place of the chemical attacks of April 7 (#Douma and #Eastern Ghouta) and explicit images of victims that were most frequently tweeted media, the visual language is rather different than that of the English space, where hashtags such as #Russia and #Trump, dominate the arena, in the second event we see #syriastrikes. The imagery here is connecting to the textual content of the hashtags, see treemaps in the Findings section.

We were rather surprised by the late 'take off' of the common solidarity hashtag #prayforsyria. It seems to be taken up only during and after the airstrikes of April 14, whereas the chemical attacks on April 7 do not trigger this hashtag significantly (it is present, but small). It pops up rather big as of April 14 and seems to connect to a wide range of other hashtags (see co-hashtag network graph in Findings section). This is even more surprising when we take into account the dominant position of this particular hashtag during the attacks on Khan Shaykhun on April 7, 2017. This attack is similar in several aspects but a year earlier this solidarity hashtag was revived much quicker than in 2018. Please note that we did not exclude other solidarity hashtags from our analysis, we chose to be inclusive and found that just one solidarity hashtag is significantly present and only in the stage of western involvement.

8. References

List your references in a standard academic bibliographic format.Bruns, A., Burgess, J. (2015 ) Twitter hashtags from ad hoc to calculated publics. In Rambukkana, Nathan (Ed.) Hashtag Publics: The Power and Politics of Discursive Networks. Peter Lang, New York, pp. 13-28.

Döveling, K., Harju, A. & Sommer, D. (2018). From Mediatized Emotion to Digital Affect Cultures: New Technologies and Global Flows of Emotion. Social Media + Society, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117743141

Papacharissi, Zizi.(2014). “Affective publics: sentiment, technology and politics.” Oxford University Press Rogers, R.A. (2018). Otherwise engaged. International Journal of Communication : IJoC (issn:1932-8036) (issn:1932-8036), Vol.12, pp.450-472 Link to presentation| I | Attachment | Action | Size | Date | Who | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

CoHashtag Analysis_Arabic_07_13.png | manage | 279 K | 11 Jul 2018 - 14:21 | MarloesGeboers | |

| |

CoHashtag Analysis_Arabic_14_21.png | manage | 212 K | 11 Jul 2018 - 14:22 | MarloesGeboers | |

| |

CoHashtag Analysis_English_07_13.png | manage | 218 K | 11 Jul 2018 - 14:21 | MarloesGeboers | |

| |

CoHashtag Analysis_English_14_21.png | manage | 329 K | 11 Jul 2018 - 14:21 | MarloesGeboers | |

| |

arab 1.png | manage | 159 K | 11 Jul 2018 - 14:32 | MarloesGeboers | |

| |

arab2.png | manage | 62 K | 11 Jul 2018 - 14:32 | MarloesGeboers |

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback