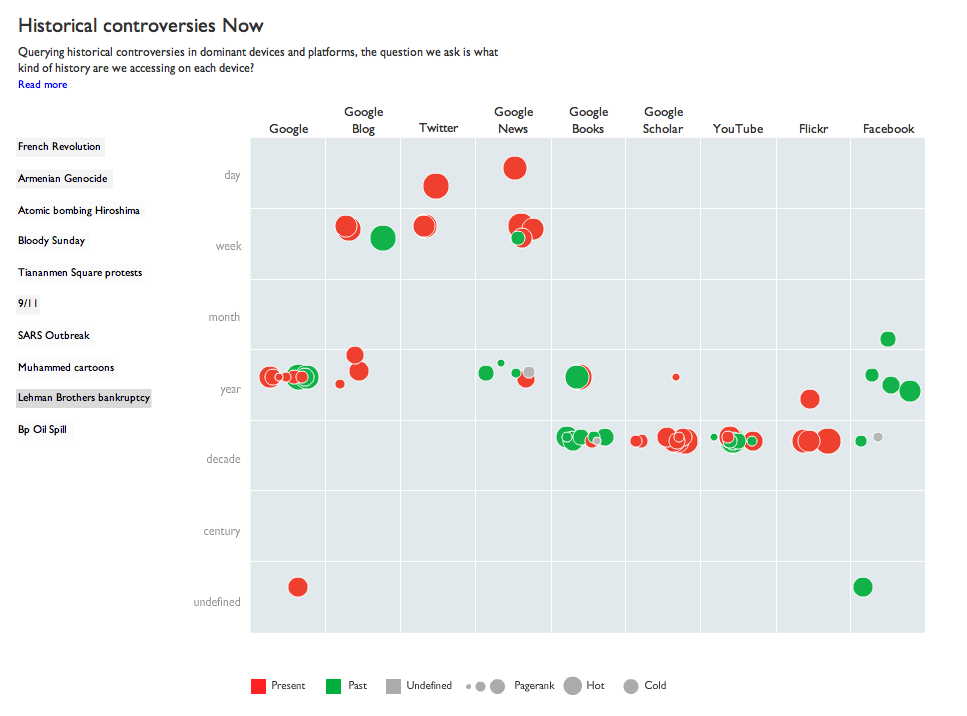

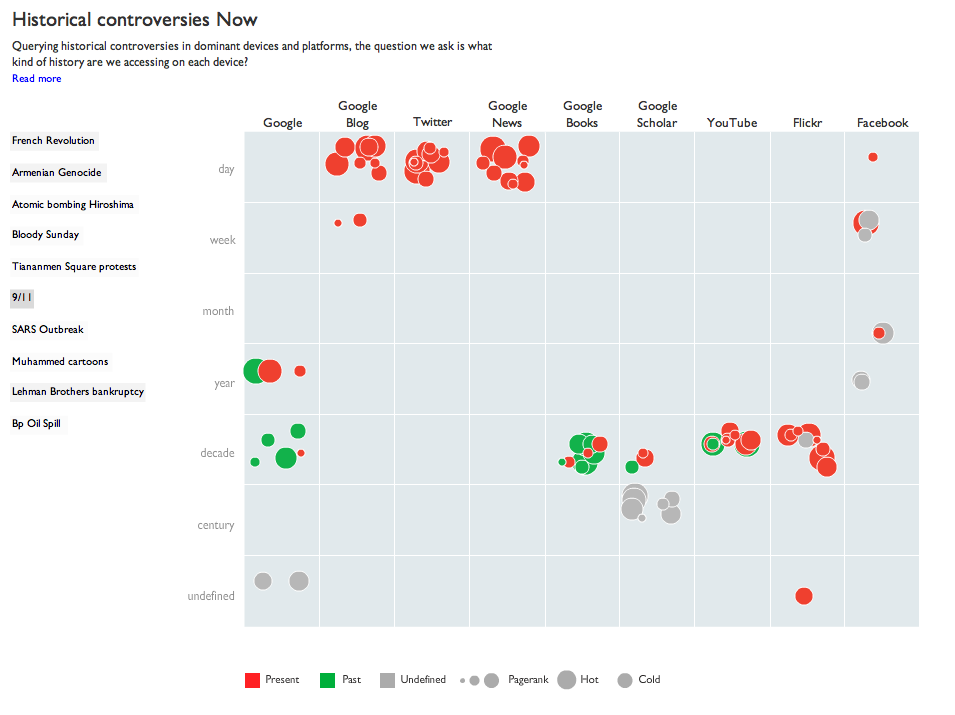

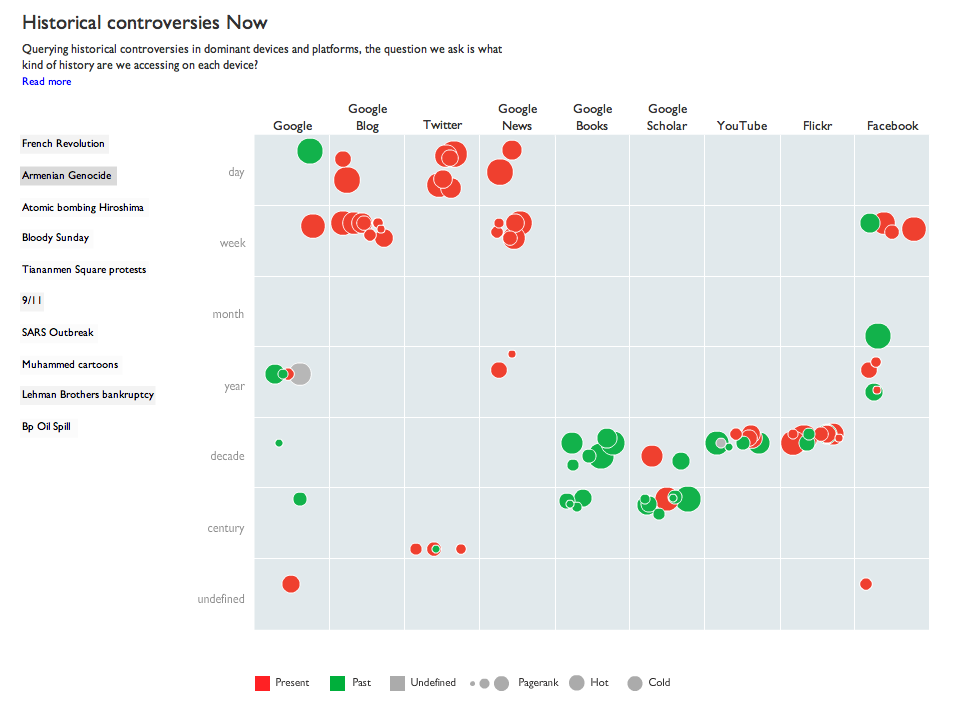

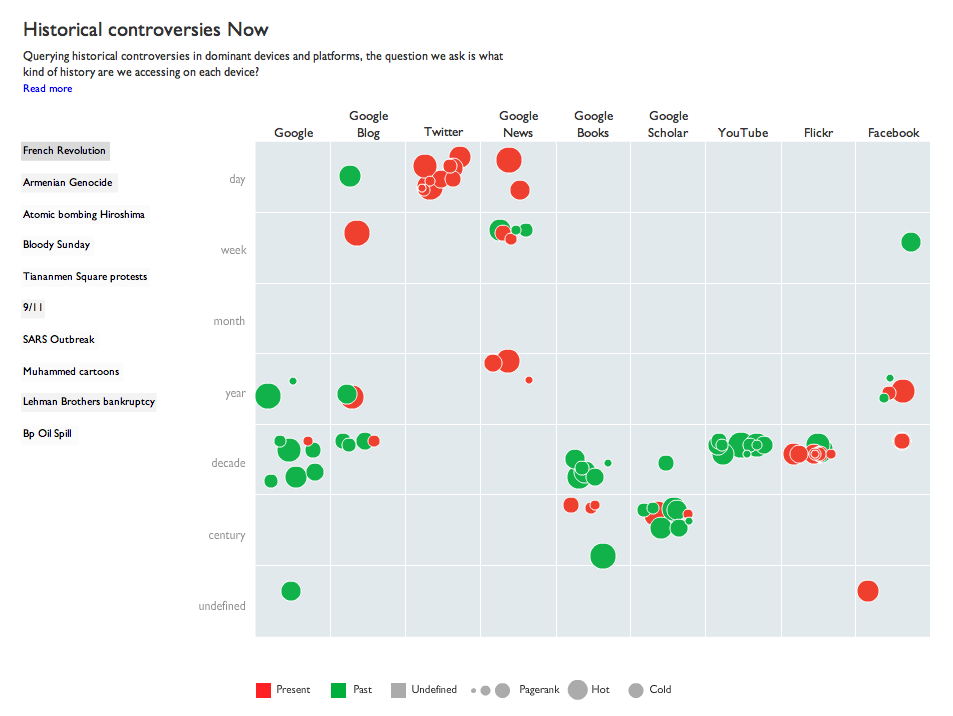

Historical Controversies Now

Team members

Demet Dagdelen, Martin Feuz, Marije Rooze, Thomas Poell & Esther WeltevredeIntroduction

Instead of going to the library or the archive, we increasingly access history, the past, through the web. But what kind of history or histories, past or pasts are we accessing online? And what does this accessing entail? Following Leong et al., we approach temporality on the web “as a multiplicity of times derived from relations between different elements (2009, 1279)." This project is specifically focused on contentious historical moments, pasts that have had and potentially still have a major emotional impact, and which have been subject of struggle. Moreover, we not interested in sites specifically devoted to history, but in the major platforms on the web. Confronting the historical events on the various platforms and opening up to a multiplicity of time we immediately realized that the traditional linear conception of time does not work online. First, most platforms do no not work in a chronological fashion, but with a reverse chronology. Second, because the platforms order sources according to ‘relevance’, the chronology of the sources as they are presented to us is radically mixed up. Third, sources do their own trick with time as well. Some focus on the historical event itself, while other rework the event. This reworking happens in a wide variety of ways, for example, by metaphorically invoking the event, by turning it into a historiographic debate, or by incorporating the event in a personal account (reading a history book, visiting a historical site, listening to a song). Crucially, in some of these reworkings, the event is actualized as controversial. These temporal complications directly informed our research, analysis, and visualization.Research questions

The above considerations translate in the following research questions:- Source time: Do we primarily find contemporary sources or historical sources in the various spheres? Does this vary across controversies?

- Historical time: Do the sources on a platform focus on the historical moment itself, or a contemporary reworking of the moment? Does this vary across controversies?

- Heat of the controversy: Is the controversy treated as settled, or is it actualized as still controversial? Does this vary across platforms and controversies?

Material

We selected (through the controversy page of Wikipedia) 5 controversies before 2000 and 5 controversies after 2000 to find out whether historical distance matters. Moreover, we selected varied set of controversies in terms of types (revolution, bombing, decease, disaster etc.) and geography (Europe, US, South-East Asia): French Revolution (1789) Armenian Genocide (1915) Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (1945) Bloody Sunday (1972) Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. 9/11 (2001) Sars (2003) Muhammad cartoons 2005-2006 Lehman Brothers bankruptcy 2008 BP oil spill 2010 We selected the major platforms through which people access the particular spheres on the Web. The idea is to examine how people are actively reworking history in a wide variety of daily activities on the web. For this reason we are not interested in specialized history sites, which turn history into an isolated activity. Web: Google search Blogosphere: Google blogsearch Twitter: Search.Twitter.com News: Googlenews Books: Googlebooks Science: Google Scholar Social networks: Facebook Encyclopaedia: Wikipedia Video: YouTube Photo: FlickrMethod

-

On 18 and 19 August, we captured for each controversy and platform the first 10 results generating potentially 1000 results.

-

From those results we recorded: a) the ranking b) date source c) title source d) description source e) url source

-

On the basis of the title, description, and in some cases by examining the actual sources, we processed the results determining whether a source: a) focusses on the historical event itself (code: past), or presents a contemporary reworking of the event (code: present)? b) treats the controversy as settled (code: cold), or actualizes it as still controversial (code: hot)? Coding the material, we let the sources speak for themselves. If a source gives an account or documents the event without ‘explicitly’ reworking it, we coded it ‘past’. Only when a source ‘explicitly’ actualized the event by interpreting it, making it problematic, or linking it to a contemporary event or moment did we code it as ‘present’ (note that this is completely independent from date of the source). The same logic was followed in the coding of the controversiality. Only when the event was ‘explicitly’ politicized as a political or scientific problem did we code it ‘hot’.

Findings

The updated tool can be found at https://files.digitalmethods.net/var/historicalcontroversies/ Presentation: http://www.marijerooze.nl/Summerschool/controversies/OldControversiesNow.swf

Temporality & Controversiality

Comparison between events:

Temporality & Controversiality

Comparison between events: - As could be expected, some events are much more actively reworked, made present, and constructed as still controversial. This comes out very clearly in the comparison between the French Revolution and the Armenian Genocide. Most of the sources, except those on Twitter and Google News attempt to give an account or document the historical event itself, without explicitly reworking it. Certainly, the French Revolution is actualized by some sources and platforms (Twitter and News), but in most cases it is not constructed as controversial. It is reworked metaphorically, or in a personal anecdote (somebody reading a book on the French Revolution). The controversy documents (pulsing) all refer to scientific debates. By contrast, the Armenian Genocide is very actively mobilized as a controversial event, which should or should not be disputed.

- The most interesting finding concerns the difference between platforms in terms of temporality and controversiality. The differences are striking. Especially Twitter and Google News are platforms where the historical events are actively reworked and made present. Whereas Google Books, Scholar, and perhaps most surprisingly Google Search give access to documents (Wikipedia, general history sites, books), which present the historical event, without ‘explicitly’ reworking it. These differences overall correspond with the actual temporal distribution of the documents.

- For the other platforms, how temporality and controversiality are constructed depends very much on the event. For example, for the French Revolution, YouTube is a platform for videos, which try to document the historical event itself without explicitly reworking it. Whereas for the Armenian Genocide YouTube becomes very much a platform of the present, where the event is actively reworked and made controversial. Striking differences can also be observed when comparing the two events on Blogs and Flickr.

References

Leong, Susan, Teodor Mitew, Marta Celletti, Erika Pearson. 2009. ‘The Question Concerning (Internet) Time.’ New Media & Society vol 11(8): 1267–1285.Data

https://spreadsheets.google.com/ccc?key=0AhvS0Q5498sVdFlvdGRkQ292NVNvMW5YTHYtU0Z6THc&authkey=COuVk8MI&hl=nl#gid=0Video

DMI Summerschool: Old Controversies Now from silvertje on Vimeo.</p| I | Attachment | Action | Size | Date | Who | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Blog_results_18082010.zip | manage | 638 K | 20 Aug 2010 - 15:17 | Main.Marije | Blog results |

| |

Flickr_1.zip | manage | 5 MB | 09 Sep 2010 - 13:31 | ThomasPoell | |

| |

Flickr_2.zip | manage | 4 MB | 09 Sep 2010 - 13:31 | ThomasPoell | |

| |

Flickr_3.zip | manage | 3 MB | 09 Sep 2010 - 13:32 | ThomasPoell | |

| |

News_results_18082010.zip | manage | 888 K | 20 Aug 2010 - 15:17 | Main.Marije | |

| |

Screen_shot_2010-09-10_at_1.51.52_PM.png | manage | 77 K | 10 Sep 2010 - 11:54 | EstherWeltevrede | |

| |

Screen_shot_2010-09-10_at_1.52.04_PM.png | manage | 78 K | 10 Sep 2010 - 11:53 | EstherWeltevrede | |

| |

Screen_shot_2010-09-10_at_1.52.14_PM.png | manage | 76 K | 10 Sep 2010 - 11:53 | EstherWeltevrede | |

| |

Screen_shot_2010-09-10_at_1.52.25_PM.png | manage | 72 K | 10 Sep 2010 - 11:53 | EstherWeltevrede | |

| |

Twitter.zip | manage | 1 MB | 09 Sep 2010 - 13:34 | ThomasPoell | |

| |

google_controversies_181010.zip | manage | 1 MB | 25 Oct 2010 - 12:22 | EstherWeltevrede |

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback