You are here: Foswiki>Dmi Web>WinterSchool2016>WinterSchool2016ProjectPages>MappingOSINTLandscapes>MappingOSINTImagesonTwitter (18 Jan 2023, AnnabelleK)Edit Attach

Mapping OSINT Images on Twitter

Tracing imagery through war and timeMapping OSINT Landscapes sub-project

Team Members

Daria Delavar-Kasmai

Ståle Grut

Annabelle Ku

Jessica Moreschi

Ari Stillman

Contents

- Introduction

- Initial Data Set

- Research Questions

- Methodology

- Findings and DiscussionConclusion

- Breaking down visual themes

- Contextualising findings and their relation to the war in Ukraine

- References

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been an increased interest in techniques and tools connected to researching and compiling data from freely available resources on the internet (The Economist, 2021). While loosely referred to as Open Source Intelligence (OSINT), derived from the military discipline where data from any open source were analysed and used to inform intelligence reports. It drew wide interest, and the techniques became increasingly notable alongside the growth of the group Bellingcat and the work it has done in connection to the downing of the MH17 flight over Ukraine in 2014 and other topics. Today, there is a large community found on Twitter that discusses tools and methods, as well as organisations, NGOs, universities and media organisations that are using and developing methodologies connected to open sources, causing the way the public receives their news to be upended (The Economist, 2023). Several datasets from Twitter tracking the hashtag #OSINT for the first ten months of 2022 were made available by the University of Amsterdam and the Digital Methods Initiative in connection with the workshop. Analysing the co-occurrences of these hashtags allows the research team to engage in “issue mapping” (Rogers et al. 2015) and the more recent “controversy mapping” (Munk and Venturini 2021) whereby affective publics (Papacharissi 2014) can be understood through their interactivity with an issue and the traceable subjectivity of the individuals who engage with said issue. In this specific project, the issue we are mapping is the Russian invasion of Ukraine and how this pans out in the larger discourse about OSINT. Specifically, the starting point for the project was an interest in analysing the visual imagery connected to the OSINT hashtag on Twitter.2. Initial Data Set

The dataset “OSINT post-Ukraine” derives from 4CAT, and can be found at https://4CAT.oilab.nl/results/c0beb466af562c3dcdc45ee70635eb46/. The source of the data is the Twitter API (v2) Search. 4CAT here queried the hashtag #OSINT on Twitter in the period of 304 days between the 1. January 2022 until the 1. November 2022. It resulted in a dataset where 477,657 tweets were captured with the following parameters:

|

|

|

3. Research Questions

We were guided by the following research questions:- What are the central visual themes in images distributed via the #OSINT hashtag on Twitter?

- How do the central visual themes change, prior to and following the Russian war in Ukraine?

4. Methodology

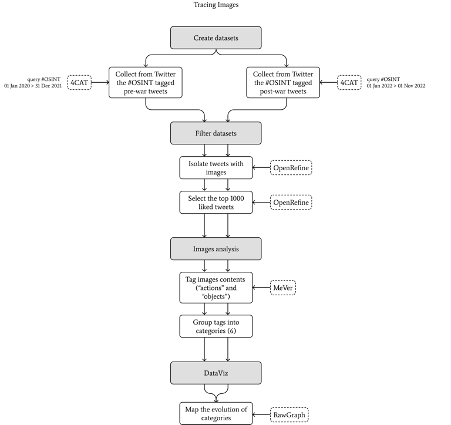

In order to analyse the images, we needed a way to isolate them in the broader dataset. While 4CAT offers a range of options to do this, the server running 4CAT that was hosting our dataset experienced high traffic during the start of the Winter School, making analysis difficult. Thus we ended up downloading the datasets locally in a CSV-format and proceeded to use the open-source software OpenRefine[1]as an alternative tool to filter the tweets that include images we would further analyse. We installed OpenRefine on a macOS system and ran it through the Chrome browser. First, we uploaded the data set and parsed it through OpenRefine. After the software displayed the various options to parse the dataset, we created our OpenRefine project. Second, we selected the image column, proceeded to click the dropdown menu, and chose “Facet” and further, “Customised facets” followed by “Facet by null”. A panel of “Facet/Filter” was displayed on the left side of the dataset. Third, by clicking “False” and “include”, the main panel listed the rows of data that only included images. Finally, we could export the refined dataset as a CSV file. In total, there were 93,686 of 477,657 tweets containing images. Sorting them by likes, we had a list of the most liked tweets containing images. Through using Google Spreadsheet, we sorted the OSINT post-Ukraine dataset by likes and discarded all but the top 1000 tweets. In order to analyse the elements of images and their content automatically, we were tasked by our facilitators with proceeding through the platform MeVer.[2] MeVer (derived from “Media Verification team”) is a platform for “understanding, searching and verifying media content” and was considered a core tool at the beginning of this research project. After registering a MeVer account, we uploaded a refined dataset containing the 1000 most liked tweets in a CSV format to the platform, and a e-mail message was sent by MeVer immediately noting “Batch import started”. Eventually, it took an estimated two hours to complete the importing of our files. While exploring the functions and metrics of MeVer, we recorded several limitations that prevented us from investigating the images from various levels. First, the column of “body” in the CSV file was removed otherwise MeVer was unable to recognise the file. Second, the platform ended up showing only 954 images from the entire 1000 tweets in “My Assets”, and no specific reason was found regarding the missing images. Subsequently, we noticed that most of the “Objects” in images were tagged incorrectly and there is a large portion of images that have no tag of “Objects”. Last, after exporting the CSV file from MeVer, we found a range of data that are essential to the research are missing in the file, such as the timestamp, link of tweet, text body, count of likes, and author. Additionally, the specific metrics offered by MeVer, such as “Actions”, “Disturbing”, “Meme” and “NSFW '', turned out less useful to our research. As an alternative approach, we chose to use Microsoft Excel to proceed with the dataset, particularly ascribing a theme to images and calculating the size of each image theme. To obtain an overview of the visual landscape, we coded the images manually into nine themes (sometimes also referred to as categories going forward)as suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006) through the process of thematic analysis (see the list below) based on the objects in the images and, if it was unclear, taking into consideration the tweet they were part of. Considering the amount of manual work, we further reduced the datasets to the top 500 tweets by likes and discarded the rest. The Pivot Tablefunctionality in Excel was applied to calculate the size of the themes on a monthly basis. Here, we were guided by the tool ChatGPT[3], an AI tool that can assist researchers (Alshater, 2022) on how to set up the table correctly. The Streamgraph from RawGraph[4]was applied to visualise the dynamics and evolutions of each type of image across the ten months (see Figure 2). RawGraph is an open-source data visualisation framework and platform. Several aspects are essential to note while using the platform to create a graph. First, the data column in the CSV file has to be organised in a certain format for RawGraphs to recognise and generate a graph. In the CSV file, only three columns were required, namely “month”, “ categories” and “count”. Since the platform was unable to detect the monthly information, numbers were used in its stead. Rather than grouping data under either “month” or “ categories”, the file should demonstrate each row as a dataset itself containing the unit of “month”, “ categories” and “count”. Once the file was formatted, it was uploaded into the RawGraphs service. By simply dragging “month” to the “X Axis”, “categories” to “Streams” and “count” to “Size” to the “Chart Variables” under “Streamgraph (area chart)”, one of the graphic frameworks RawGraphs provided, a drafted graph and a sidebar of “Customise” will be demonstrated for adjusting the parameters. As the final step, Figma[5] was used to illustrate the protocol (see Figure 1) and design the project poster. Visual themes in images:- “Building”, images included destroyed buildings and cities.

- “Instructions (coding, tools)”, screenshots of coding panels providing instructions for doing OSINT or generally coding lifehacks. Most of the instructions are not relevant to the war.

- “Memes”, memes that are relevant to the war or OSINT in general.

- “Military equipment”, images could include airplanes, missiles, cars or boats, etc.

- “OSINT community”, infographics, posters, and methods associated with the practice of OSINT. Most of the images are not necessarily related to the war and could be about information gathering, cybersecurity, etc.

- “People” were typically government officials, soldiers, and citizens. Frequently tied to demonstration of technologies such as i.e. facial recognition.

- “Satellite images”, satellite images, frequently related to the war.

- “War infographics”, infographics related to the war, including maps and weapons analysis.

- “Removed”, tweets added to the dataset but that had since been removed, either by the users themselves or Twitter’s moderation team.

Figure 1: Overview of our protocol from dataset creation to final visualisation. Illustration: Jessica Moreschi

Figure 1: Overview of our protocol from dataset creation to final visualisation. Illustration: Jessica Moreschi

5. Findings and Discussion

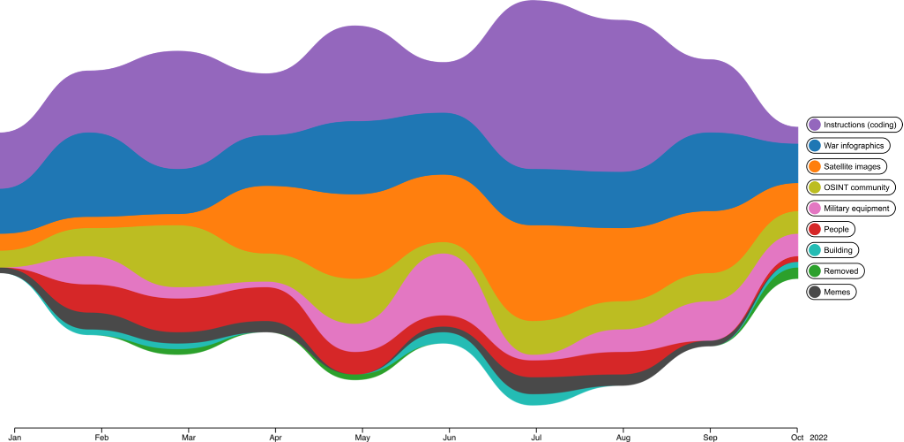

In our sample of “most liked images”, the “Instructions” theme was the most prevalent – it contains lifehacks, coding methods, and coding screenshots largely pertaining to OSINT. The second most prevalent theme was “Satellite images” usually depicting some area of Ukraine. Notably, 68% of the top satellite images were tweeted by the same user, whereas the other themes demonstrated much broader sourcing.[6] The most specific theme was “War infographics” while the least specific theme was “Buildings” that we could not readily identify. See Figure 2 below for an illustration of the theme's size over time. Additionally, we identified 30% of images that seemed not to have any obvious salience to the invasion of Ukraine in the “Instructions” theme. Many of these were screenshots of programming code seemingly encouraging OSINT practices. However, it is possible that these tweets could have been introduced to the datastream to discourage following the topic as articulated by Verkamp and Gupta (2013). The breakdown of the monthly changes across our defined image theme was shown as following: Figure 2: Visual themes/categorisation of the images from the top 500 liked tweets with the hashtag #OSINT. Where multiple images appeared, the first image from the post was evaluated. Illustration: Jessica Moreschi

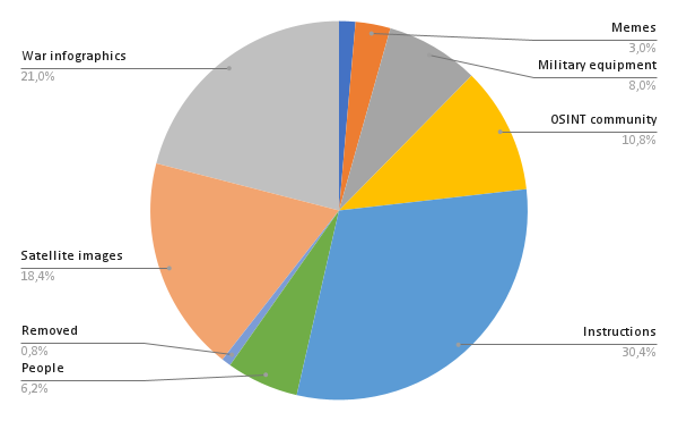

Figure 2: Visual themes/categorisation of the images from the top 500 liked tweets with the hashtag #OSINT. Where multiple images appeared, the first image from the post was evaluated. Illustration: Jessica Moreschi Figure 3: Breakdown of themes/categories in the final dataset

Figure 3: Breakdown of themes/categories in the final dataset

Breaking down visual themes

In the pie chart (see Figure 3) we can observe our themes relative to the total percentage of content. As mentioned, we had some hypotheses before making this chart, and, for example, we expected to see much more in the theme of “Memes”, as memes are a popular theme in general on Twitter. However, this was not the case. Tracing the images back to their original context, by visiting the original tweets URLs, we can additionally note that users rarely explain or describe the meme posts that we studied. The uncommonness of the “Building” theme surprised us as well because a lot of images of destroyed buildings can be seen on Twitter, social media and in the news. This could suggest that popular OSINT tweets do not specifically contain a lot of images of buildings. The next theme is “People''. This was an interesting discovery too, as there is a lot of interest around the use of facial recognition to find culprits of i.e., the Bucha massacre. Our analysis found that the theme mostly included images of recognised Russian soldiers or investigations about Russian or Russia-associated officials. The “Military equipment” theme,which made up 8% of our dataset, includes both photos and weapons illustrations with descriptions. The seemingly low number could be explained by several factors. Some information about weapons systems are highly classified, and both the Ukrainian government and governments of European Union member states have requested that this information should not be disseminated, as it may negatively affect the transfer and movement of weapons to and in Ukraine. Also, photographing any type of weapon is considered a criminal offense in Ukraine. We suggest that the lack of information and deliberate secrecy concerning this theme has significantly contributed to the scarcity of such images in our dataset. The next theme, “OSINT community”, is divided when it comes to its connectedness to the topic of the war in Ukraine. Our justification for both the name and the broader theme goes back to tweets where we observed that the main focus was concerning various OSINT practices. The theme is a significant section of our dataset – 10,8 %. This resonates with the initial query that formed the central theme of our dataset: the keyword OSINT. The theme of “Satellite images” is prevalent in our findings, making up almost 20% of our dataset. The movement of troops, material, and front lines have been central to the news coverage of Ukraine, as it is in any conflict, and satellite images have proven central to confirming new updates from the battlefield (The Economist, 2022). The “War infographics” is a broad visual theme that combines several “subthemes”. These are maps, weapons analysis, successes on the battlefield, and the like. We establish that related to the war in Ukraine, this theme is the most prevalent. Figure 4: A sample of images coded with the theme “War Infographics” in our dataset.

Finally, to our surprise, the largest theme was images not at all related to the topic of the war in Ukraine and not even related to the topic of OSINT. This topic which we called “Instructions” is 30,4%. This theme includes programming screenshots, hacking aesthetics, OSINT expert help requests, screenshots, as well as material seemingly unrelated to the OSINT topic.

Figure 4: A sample of images coded with the theme “War Infographics” in our dataset.

Finally, to our surprise, the largest theme was images not at all related to the topic of the war in Ukraine and not even related to the topic of OSINT. This topic which we called “Instructions” is 30,4%. This theme includes programming screenshots, hacking aesthetics, OSINT expert help requests, screenshots, as well as material seemingly unrelated to the OSINT topic.

Contextualising findings and their relation to the war in Ukraine

The following subsection discusses our findings over the timeframe of our data and places them in their temporal-historical context. January: During the pre-invasion period, a majority of the images fit the instruction theme. This is, as mentioned, consistently the largest theme throughout the timeline of our dataset. February: We can see a peak in the “war infographics” theme this month. As noted by The Economist (2022), “Russia’s manoeuvres” during this period was “a coming-out party for open-source intelligence” where a growing community was tracking the buildup of the Russian forces near the Ukrainian border via satellite imagery and other open sources, prior to the invasion happening on the 24th of the month. A bump in the chart can be observed in the military equipment theme as images of Russian tanks with symbols such as “Z” start to appear in the dataset. Also, there are a lot of cases of OSINT practitioners debunking Russian propaganda – claiming to hit Ukrainian military drones, such as Bayraktar TB2. The other themes do not exhibit significant changes. March: March shows a big decline in the war infographics theme. March was a month when the war in Ukraine was a prolific topic in the news media. Additionally, swaths of OSINT practitioners were investigating the war from afar. On March 16, Russian forces dropped a powerful aerial bomb on the Mariupol drama theatre, where approximately 1000 civilians were hiding (Hinnant, Chernov & Stepanenko, 2022, which caused a big spike in war infographic images. From 24th February to 1st April, many towns and villages in the Kyiv region were under attack or occupation by Russian troops. In the middle of March, we can observe a beginning of a peak in both the “satellite” and “war infographics” themes. April: The peak in satellite and war infographics continues. We can also observe a small bump in the theme “people”. Only at the beginning of this month, Ukrainian forces were able to liberate the region and discover apparent war crimes perpetrated by Russian armed forces. When images emerged of bodies of dead civilians lying on the streets of Bucha, a suburb of Kyiv — some with their hands bound, some with gunshot wounds to the head — Russia’s Ministry of Defense denied responsibility and suggested in a Telegram post that the bodies had been recently placed on the streets after “all Russian units withdrew completely from Bucha” around March 30.[7] Russia claimed that the images were “another hoax” and called for an emergency U.N. Security Council meeting on what it called “provocations of Ukrainian radicals” in Bucha. However, a later analysis of satellite images conducted by the “visual investigations” team at the New York Times refuted claims by Russia that the killing of civilians in Bucha occurred after its soldiers had left the town and that many of the civilians were killed more than three weeks earlier, when Russia’s military was in control of the town (Al-Hlou et al., 2022). Possibly stemming from this significant story, where satellite imagery was central, we can observe a spike in satellite images shared on the #OSINT hashtag on Twitter around this time. May: We can see a big spike in the “Instructions”, where the images are not directly connected to the war in Ukraine. The other themes have a noticeable decline. One significant event that might contextualise this change in focus was US President Joe Biden signing the law on lend-lease for Ukraine (Desiderio, 2022). It was also a time when Ukrainian authorities asked citizens not to share updates on images, in preparation for a counteroffensive and prisoner exchanges, similar to events in Kherson (Sky News, 2022). June: The big peak in war infographics and satellite images is caused by the events of the liberation of Zmiinyi Island (Snake Island), where i.e. a satellite photo of Snake Island was published by the private satellite operator Maxar Technologies. On their Twitter account, they posted pictures dating back to June 30.[8]On June 27, a missile strike was conducted in the city center of Kremenchuk, hitting a shopping mall and road machinery plant (Tondo and Sauer, 2022). A fire subsequently broke out leaving at least 20 people killed and injuring at least 56. July: The decline continues in all of the themes even though attacks on Ukrainian cities continue: such as in Kharkiv, Mykolaiv, and the regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. August: There is a small but stable decrease in all themes. There were no significant changes on the front line during August. In general, this is the first month when Russians did not capture a single city or a single large settlement. However, battles were still fought in the eastern regions of Ukraine, as in previous months. September: We can observe a peak starting to form gradually, in all the themes, except instructions.The Ukrainian army conducted an effective counteroffensive operation in the Kharkiv region and during the period 06-13.09.2022 liberated almost all of the occupied areas including the cities of Balakliya, Izyum, and Kupyansk (a total of 300 settlements in the Kharkiv region, 3,800 km² of territory, where 150,000 people live). On September 13, the first Iranian-made unmanned aerial vehicle (drone), "Shahed-136'' was shot down in the city of Kupyansk. On September 21, Putin announced a decree on partial conscription of citizens to assist the invasion, and between September 23-27, Russia held pseudo-referendums in the captured territories of Ukraine (except Crimea) with the objective of including the occupied regions into Russia. October: We can see a peak occurring in all themes, except instructions, possibly due to its frequent disassociation with the war.On October 8, the Kerch Strait Bridge was partially disabled as a result of a truck explosion. On October 10, Russia launched a massive missile strike across Ukraine, which was presented as revenge for the explosion on the bridge. This was particularly symbolic because this was “a birthday present for Vladimir Putin” on October 7th (Specia, 2022). On October 10, Russian troops launched the first large-scale missile attack on the energy infrastructure of Ukraine. The Russians used air-, sea-, and land-based cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, anti-aircraft guided missiles, and reconnaissance and attack UAVs of the Shahed-136 type. Ukrainians described this attack as “it felt like the 24th of February again” (Gerdžiūnas, 2022).6. Conclusion

In this brief project, we engaged in a visual issue mapping of OSINT discourse pertaining to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. We isolated the 500 most popular tweets with images, coded the first image of the tweet with the pertinent theme, and established which were the most and least prevalent as well as specific. In interpreting our findings across a Streamgraph, we were able to contextualise changes in thematic prevalence and overall engagement figures in light of events relating to the war. This project analysed a large dataset of Twitter posts using the hashtag OSINT between January and October 2022. By performing a visual analysis of images attached to the 500 most liked tweets in the dataset and coding them into themes, we found spikes of visual imagery in certain themes that correspond to events on the ground in Ukraine. Joint spikes in #OSINT and #Ukraine activity map corresponds with especially evocative episodes during the war. Notably, these were a) Russia killed dozens of Ukrainian civilians in April and b) an event in July when Russian forces sought to capture Zmiinyi Ostriv (Snake Island) while being fought off by Ukrainian armed forces. Both of these episodes captivated a global public, likely contributing to greater engagement of both the #OSINT and #Ukraine hashtags. The visual theme of “instructions”, often connected to OSINT was the most prevalent and saw increases coinciding with the aforementioned activities. The sharing of satellite imagery also increased during these events. Other identified themes remained relatively stable or experienced minor drops throughout our dataset. By continuing to follow #OSINT and #Ukraine to increase the temporal reach of the data sample or to replicate this study with another OSINT-related topic over a longer period of time for comparison, future research can learn what type of themes map onto various issues. This could be helpful for understanding the issues that prompt OSINT engagement as well as the forms it takes. Indeed, our research has several important limitations. First, our research team was learning the software and tools as we went – often having to work around the technical and practical limitations of i.e. tools like 4CAT and MeVer. As i.e. MeVer is a work in progress, and we were encouraged by workshop facilitators to “break the tool” to understand its limitations, this was expected. We further experienced issues both with server bandwidth as well as the learning curve of understanding the right processes by which to analyse our data. This impediment may have impacted our results, as having a better understanding of the tools both theoretically and through hands-on experience would have made it a more seamless process. Second, as we engaged in this research as part of a data sprint, we were under time pressure to complete it in a short period of time. Having more time to learn the tools and analyze the data may have yielded different approaches and results. Third, our suggested main tool for analysing visuals, MeVer, did not tag objects correctly and did not provide tags for a large portion of the images, resulting in us having to thematise and coding them manually. Also, the MeVer tool erased important data we uploaded to the tool (such as timestamp, like count, etc.) rendering it virtually impossible to reconnect the data generated by the tool with our initial dataset. We were not aware of this until late in the process of working with the tool, so it took a large chunk of time to download and upload the images in alternate ways. As a result, it was not very useful to use the current MeVer software for our project, and we ended up abandoning it mid-way through the winter school. As such, in order to make the project more manageable for manual analysis, we cut the sample down manually in Google sheets to the images from the top 500 most-liked tweets. Further, the time pressure precluded us from being able to establish the proper context for each tweet, investigating the users’ history, and other more thorough research practices that could help establish further validity of our data and findings. Finally, we were limited by the dataset itself – both in terms of when data ceased being collected and how it was collected. The research team may have pulled the data differently, thereby potentially producing different insights. We also lacked the November and December data, which would be very interesting to look at, due to the central event of the liberation of Kherson that happened on the 11th of November 2022 (The Economist, 2023).7. References

- Al-Hlou, Y., Froliak, M., Hill, E., Browne, M. and Botti, D. (2022). New Evidence Shows

- How Russian Soldiers Executed Men in Bucha. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/19/world/europe/russia-bucha-ukraine-executions.html. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Baxevanakis, S., Kordopatis-Zilos, G., Galopoulos, P., Apostolidis, L., Levacher, K., Schlicht, I.B., Teyssou, D., Kompatsiaris, I., & Papadopoulos, S. (2022). The MeVer DeepFake Detection Service: Lessons Learnt from Developing and Deploying in the Wild. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Multimedia AI against Disinformation (MAD '22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1145/3512732.3533587.

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oaor

- Desiderno, A. (2022). In the fight against Putin, Senate unanimously approves

- measure that once helped beat Hitler. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/04/06/senate-unanimously-approves-lend-lease-00023668. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Gerdžiūnas, B. (2022) “‘It Feels like February 24 Again.” War Returns to Kyiv’”. Lithuanian National Radio and Television (LRT). https://www.lrt.lt/en/news-in-english/19/1799564/it-feels-like-february-24-again-war-returns-to-kyiv. Accessed 17. January 2023.

- The Economist (2021). Open-source intelligence challenges state monopolies on information. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/briefing/2021/08/07/open-source-intelligence-challenges-state-monopolies-on-information. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- The Economist (2022). A new era of transparent warfare beckons. The Economist.

- https://www.economist.com/briefing/2022/02/18/a-new-era-of-transparent-warfare-beckons. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- The Economist (2023). ‘Open-Source Intelligence Is Piercing the Fog of War in Ukraine’. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/interactive/international/2023/01/13/open-source-intelligence-is-piercing-the-fog-of-war-in-ukraine. Accessed January 17, 2023.

- Hinnant, L., Chernov, M., Stepanenko, V. (2022). AP evidence points to 600 dead in Mariupol theater airstrike. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/Russia-ukraine-war-mariupol-theater-c321a196fbd568899841b506afcac7a1. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- M Alshater, M. (2022). Exploring the Role of Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Academic Performance: A Case Study of ChatGPT. Available at SSRN.

- Papacharissi, Z. (2015). Affective publics: Sentiment, technology, and politics. Oxford University Press.

- Peeters, S., & Hagen, S. (2022). The 4CAT Capture and Analysis Toolkit: A Modular Tool for Transparent and Traceable Social Media Research. Computational Communication Research 4(2). Available at https://computationalcommunication.org/ccr/article/view/120

- Ramsay, S. (2014). The hermeneutics of screwing around; or what you do with a million books. Pastplay: Teaching and Learning History with Technology, 111-20.

- Rogers, R., Sánchez-Querubín, N., & Kil, A. (2015). Issue mapping for an ageing Europe. Amsterdam University Press.

- Sky News. (2022). Ukraine War: Mystery in southern Ukraine after news blackout.YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c2uhHQIuHCc. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Specia, M. (2022) “‘Happy Birthday, Mr. President’: Ukrainians Celebrate the Bridge Blast with Memes.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/08/world/europe/ukrainians-crimea-bridge-memes.html. Accessed January 17, 2023.

- Tondo, L. and Sauer, P. (2022). At least 16 dead as Russian missile hits shopping centre in Ukraine. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jun/27/russian-missile-hits-shopping-centre-ukraine-kremenchuk. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Venturini, T., & Munk, A. K. (2021). Controversy Mapping: A Field Guide. John Wiley & Sons.

- Verkamp, J. P., & Gupta, M. (2013). Five incidents, one theme: Twitter spam as a weapon to drown voices of protest. In 3rd USENIX Workshop on Free and Open Communications on the Internet (FOCI 13).

[1] https://openrefine.org/

[2] https://mever.gr/

[3] https://openai.com/

[4] https://www.rawgraphs.io/about

[5] https://www.figma.com/

[6] As another workgroup focused on the authors of tweets on the OSINT hashtag, we did not explore this issue further.

[7] https://t.me/MFARussia/12230

[8] https://twitter.com/maxar/status/1542533336299515905

Attachments

[2] https://mever.gr/

[3] https://openai.com/

[4] https://www.rawgraphs.io/about

[5] https://www.figma.com/

[6] As another workgroup focused on the authors of tweets on the OSINT hashtag, we did not explore this issue further.

[7] https://t.me/MFARussia/12230

[8] https://twitter.com/maxar/status/1542533336299515905

Attachments

- Mapping-OSINT-Images-Video.mp4: Mapping-OSINT-Images-Video

- Mapping-Osint-Images-Poster. Illustration: Jessica Moreschi

Edit | Attach | Print version | History: r4 < r3 < r2 < r1 | Backlinks | View wiki text | Edit wiki text | More topic actions

Topic revision: r4 - 18 Jan 2023, AnnabelleK

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback