Uses and Users of Climate Change Vulnerability Indices: Mapping the Reputation of Indices in Climate Change Adaptation Spaces

Issue experts

Sönke Kreft, Matthew McKinnon

Project leaders

Esther Weltevrede, Alice Caravani, Mathieu Jacomy, Anders Munk, Peter Gerry

Team members

Rebecca Cachia, Fernando van der Vlist, Susan Clandillon, Pascal Janssens, Stefania Guerra, Simone Pirini, Marieke van Dijk

- Uses and Users of Climate Change Vulnerability Indices: Mapping the Reputation of Indices in Climate Change Adaptation Spaces

- Summary of key findings

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Literature review

- 3. Methods and results

- 5. Discussion and suggestions for further research

- 6. Footnotes

- 7. References

Summary of key findings

- From our analyses of bilateral and multilateral funding allocation, we were able to identify and quantify different funding strategies associated with particular countries and indices. Most notably, it seems that some indices such as the HDI and GAIN diverge focus on a large number of countries that are highly vulnerable and least developed, while some countries such as Japan are allocating their funding to particular countries that are categorised as having medium or low vulnerability.

- From our analysis of the Web corpus, we found that vulnerability indices typically did not appear (i.e. are not mentioned) in the same spaces or contexts. Rather, it appears that the indices have their own (specialised) spaces in which they are mentioned by in isolation from the other (related) indices.

- From the highly authoritative UNFCCC national communications documents, we were able to quantify index mentions over time and found that the most frequently mentioned indices are not explicitly vulnerability indices, but rather the ones associated with human development (HDI), human poverty (HPI) and coastal vulnerability (CVI).

- From our analysis of the Google Scholar Web space, we found indicators of an increased interest in vulnerability indices by the academic communities over the past eight years. However, confirming our earlier findings in other spaces, the different types of indices we have identified (vulnerability indices, economic models, and humanitarian indices) within this academic space do not seem to be in competition with each other in academic publications. At the same time, such competition was found between the indices inside these categories insofar as these indices were cited from the same journals in our corpus.

- Finally, we present some initial results from our analysis of the news sphere, where we encountered the Climate Change Vulnerability Monitor (CVM) as the most frequently mentioned index.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and objectives

In this report we partially document the process and results of the second Electronic Maps to Assist Public Science (EMAPS)1 Amsterdam Sprint. As such, it follows up on the questions and findings from the earlier Paris Sprint, which focused on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations as an important arena for global governance of climate change and adaptation.2 Adaptation, or the adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities (Glossary of Climate Change Acronyms, 2010), entered the UNFCCC arena in 2000 as the inevitability of climate change was acknowledged and the need for adaptation became an international issue for both developed and least developed countries (LDCs) alike. It is in this context, and as investigated in the Paris Sprint, that adaptation became a matter of concern with regards to the politics of financial flows and funding allocation.

The second sprint set out to map controversies and mechanisms for coping with climate change vulnerability in different regions and by different actors.3 The objective is to gain a comprehensive understanding of whether the Web can provide a meaningful basis for the production of an enhanced interest of a wider public in issues of science and technology that goes beyond merely receiving end results and instead includes the members of this public as potential participants in science in the making (Objectives). The proposed model to meet this objective is to trace in the Latourian sense of following the actors themselves in the framework of actor-network-theory (ANT) as well as to map the heterogeneous networks that emerge as issues of science and technology, that is, the continuous entanglements between, on the one hand, the production of (scientific) facts, and on the other, the proliferation of pluralism (ibid.).

More specifically, the focus of the sub-projects presented in this report is, firstly, on the uses and users of climate change vulnerability indices, and secondly, to some degree, how these relate to adaptation funding allocation. By means of establishing a basis for this inquiry, the nineteenth session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 19) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which took place in November 2013 in Warsaw, culminated in the establishment of an international mechanism for loss and damage. According to the UNFCCC Decision CP.19, such an international mechanism include[s] functions and modalities to address loss and damage associated with the impacts of climate change in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. (Warsaw Climate Change Conference). Some of the adverse effects prompting this arrangement include extreme weather events and sea level rise. Crucially, as Rogers observes, the same document acknowledges that loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change includes, and in some cases involves more than, that which can be reduced by adaptation. This recognition of the limits of adaptation marks the opening up of the climate change debates to a new phase that deals with loss and damage as a consequence of the failure to adapt and to mitigate (Rogers, Coping with Vulnerability to Climate Change). This means that it marks a move away from the debate of climate change or climate variability to the general acceptance of climate change as something that we can and have to cope with, and consequently, distinguishing between those who make decisions about risky matters of concern, and those who are (disproportionately) affected by them. Taking this into account, we approach the task of mapping these controversies from a perspective of risk cartography.

A cartography of risk deploys a methodological framework as well as a set of techniques that may be used to explore and visualise issues involving risk and threat. Methodologically speaking, we will be feeding off controversies in order to circumvent the implausible task of setting up a priori boundaries to the controversy at hand (Latour [2005] 2007, 52). This means that the more actors act as mediators those actors that transform, translate, distort, and modify the meaning or the elements they are supposed to carry (39) the better the controversy lends itself to being mapped. Relating this back to the main focus of the inquiry, we thus aim to map competing resources, that is, the management of risk4 and compensation in light of insurmountable global and manufactured uncertainties (Beck [2007] 2009).

1.2. Research questions

Based on close collaboration with issue experts (or alpha-users)5 and a review of academic literature, we posed one overarching research question that will then be fleshed out by the various sub-projects and their analytical questions:

- Which particular climate change vulnerability indices and/or indicators that are relevant in the selected decision-making contexts are competing and where can we locate this competition?

In other words, how do their traces resonate in a series of different data sets (all of which are either native to or have been retrieved via the Web)?

2. Literature review

For a long time, the issue of vulnerability to environmental change has been a central concern of geography. One of the key messages from these geographic studies is that the causes and consequences of social and environmental change are complex and defy simple explanations (Barnett, Lambert and Fry 2008, 103). Since the 1990s there have been quite a few projects that attempted to develop indices that claim to measure vulnerability to social and/or environmental change (Ibid.). Such indices typically combine multiple indicators of a variable into a single measure thus ordering a set of entities with respect to quantitative attributes or traits. As such, they are integral to many contexts that require systematic approaches to decision making processes, especially those that concern the management or governance of risk (cf. Renn and Graham 2004; Klinke and Renn 2005; Beck [2007] 2009). Broader debates about climate change vulnerability indices and indicators include those concerning global environmental change, climate change adaptation, mitigation, vulnerability, resilience, as well as the question of where the debate itself should take place, and who should be part of it.

2.1. Vulnerability and adaptability

As observed by a number of experts, there is a growing body of literature on vulnerability and adaptation that contains a sometimes bewildering array of terms: vulnerability, sensitivity, resilience, adaptation, adaptive capacity, mitigation, risk, hazard, coping range, adaptation baseline, and so forth (McCarthy et al., 2001; Adger et al., 2002; Burton et al., 2002). The relationships between these terms and what they mean is not always clear, as the same term may have different meanings when used in different contexts and by different authors (Brooks 2003, 2). Over time, however, some of these differences seem to have become a little clearer, as popular definitions emerge and stick. One clear distinction is between resilience and adaptation, which are now thought of as opposites. As Barnett, Lambert, and Fry observe: [m]ost definitions of resilience are variants of Holling's (1973) foundational definition of it as the ability of these systems to absorb changes of state variables, driving variables, and parameters, and still persist (17). So, a resilient ecosystem is not one in which populations remain stable or where change is resisted, but rather where change is accommodated or absorbed in ways that do not fundamentally alter ecosystem structure (Folke et al. 2002). (2008, 104). Adaptation, on the other hand, does require such fundamental alterations. By extension, this distinction implies that adaptation funds should not just take into account the compensation (financial or otherwise) of hazards or extreme weather caused by climate change, but should enable the capacity to make such fundamental alterations to social and environmental systems in advance. There is, in other words, a fundamental anticipatory component to adaptation that is not part of resilience.6 This then interpellates even more actors, strategies, variables, and so on into an issue that is already extremely complex.

Vulnerability to environmental change as a conceptual framework has been a powerful analytical tool for describing states of susceptibility to harm, powerlessness, and marginality of both physical and social systems, and for guiding normative analysis of actions to enhance well-being through reduction of risk (Adger 2006, 268). As with the array of terms mentioned earlier, it has also been used in many different ways (Füssel 2006, 2). Füssel notes that the scientific use of the concept is different from its ordinary use, because it has roots in geography and natural hazards research thus representing a conceptual cluster for integrative human-environment research (3). By now it is adopted as a central concept in all kinds of research contexts such as hazards and disaster management, ecology, public health, poverty and development, secure livelihoods and famine, sustainability science, landscape change, and climate impacts and adaptation (ibid.; Brooks 2003, 2). The now usually adopted definition comes from the Third Assessment Report (TAR) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which defines vulnerability as: the degree to which a system is susceptible to, and unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change, including climate variability and extremes. Vulnerability is a function of the character, magnitude, and rate of climate change and variation to which a system is exposed, its sensitivity, and its adaptive capacity (McCarthy et al. 2001, 995; Adger 2006, 269; Hinkel 2011, 200). Vulnerability thus frames social-ecological systems; systems that are neither reducible to social nor to environmental variables alone, but rather lend (part of) their complexity to the interactions between complex, multivariate, dynamic systems. In support of this view, Barnett, Lambert, and Fry argue that [v]ulnerability is about values at risk, and identification of vulnerable environments cannot purport to be meaningful if it does not recognise the relative values of environments at risk to diverse groups. This is not to say that attempts to understand environmental change independent of social impacts are not useful, but it is to say that the significance of those changes only arises through consideration of their impacts on the values of social groups (2008, 116).

2.2. Indicators and criteria for measuring vulnerability

The real challenge for vulnerability research then became the task to develop robust and credible indicators and criteria for measuring vulnerability (Birkmann 2006; Eriksen and Kelly 2006; Adger 2006). In fact, according to Barnett, Lambert, and Fry, there have been so many attempts leading Parris and Kates (2003) and the National Research Council (2000) to conclude that there is no consensus on their appropriateness, theoretical and scientific basis, and appropriate level of specificity or aggregation (106). Their own particular analysis concerned insights from the Environmental Vulnerability Index (EVI), developed by the South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC). Among many other things, they find that this index implies that the cause of environmental vulnerability of a country is only its population because it does not consider the larger political economy of vulnerability (110). They even go as far as to call the EVI an antidevelopment index because it avoids directly considering social losses and could be seen as rewarding situations of low economic development (ibid.). Another important critique that is presented lies in the ranking of its indicators, or rather lack thereof. The EVIs 50 smart indicators are arranged by aspects of vulnerability (Hazards, Resistance and Damage), but all treated the same, and thus do not acknowledge any kind of priority. Yet, the list of indicators in the Hazards column is more than twice as long as the other two columns. This means that it will not be enough to create multidimensional indices that would potentially exhaust all possible indicators, because each indicator is also valued differently by different actors (which also reflects the difficulty of defining vulnerability in the first place). Here we can thus see the importance of Becks concept of relations of definition: any scale or index ultimately relies on its conceptual outlines. Consequently, Hinkel (2011) presents an analysis of six diverse types of problems that vulnerability indicators are meant to address according to his review of the literature: (i) identification of mitigation targets; (ii) identification of vulnerable people, communities, regions, etc.; (iii) raising awareness; (iv) allocation of adaptation funds; (v) monitoring of adaptation policy; and (vi) conducting scientific research. (198). Based on this, he finds that only the second type of problem can be addressed by vulnerability indicators, but only at small and local scales, causing him to question the concept of vulnerability itself and the applied methodologies (ibid.).

2.3. The sciencepolicy interface

Considering all this, it should come as no surprise that the issue of measuring climate change vulnerability and adaptive capacity by means of indicators also divides policy and academic communities (Hinkel 2011, 198). This is where the issue of competing resources, mediated by indices actually seems to take centre stage. Burton (2002) has observed the lack of development of adaptation as a policy response as opposed to mitigation. This asynchrony clearly shows the focus of research on biophysical sciences of impacts and adaptation, while research on ways and means of adaptation focuses on socio-economic determinants of vulnerability (145). Adger et al. (2003) further complicated the concept of adaptability by arguing that some groups in society are more sensitive and vulnerable to the risks posed by climate change than others. As such, they promote adaptive capacity in the context of local natural resource management and international agreements and actions regarding competing sustainable development objectives (179). Regarding issues of scale (in both directions of time and space), Brooks et al. (2005) present a novel set of indicators for measuring vulnerability and the capacity to adapt to climate variability and climate change by extension, using empirical data on the national level and over longer periods of time. The analysis showed that vulnerability is strongly associated with areas that recently experienced conflict, and adaptive capacity with governance, civil and political rights and literacy (151). Similarly, Füssel (2010) disproved the assertion that countries who have contributed least to climate change have the highest vulnerability to its adverse effects by examining multiple indices of vulnerability to climate change. The study finds a double inequity between responsibility and capability, and vulnerability of food security, human health and coastal populations (597). Each case shows the recurring issue of who is responsible for doing the issue. At the bottom of this lies the question whether this is a political or scientific issue (Barnett, Lambert, and Fry 2008; Klein 2009). For instance, vulnerability has political dimensions as a non-quantifiable attribute that cannot be objectively measured and which is the outcome of a negotiation process (Klein 2010; Klein and Möhner 2011), and the question of which countries (typically, rather than regions or cities) are particularly vulnerable to adverse effects of climate change is one of science as much as politics (Klein 2009, 2010). In sum, the lack of an agreed scale for measuring countries vulnerability to climate change and conflicting interpretations of vulnerability itself (Füssel 2010, 597) both complicate the issue. As Klein (2010) exclaimed, Science Doesnt Have the Answer!.

3. Methods and results

3.1. Bilateral and multilateral funding allocation

Research on this sub-project builds on the funding data sets compiled during the Paris EMAPs data sprint in 2013. These funding data sets relate to bilateral and multilateral funding.7 Notably, the rationality for requesting or pledging funding may be motivated by many distinct factors. Countries may pledge funds as a result of geopolitical motivations rather than the assessed vulnerability of the recipient country, while recipient countries may not wish to consider assessed vulnerability at all in their application for funding. Thus, this project explores the extent to which vulnerability assessments are effective in negotiating and attracting adaptation funds. This investigation is framed by the following research question:

- Is there a correlation between high vulnerability ranking and funding?

3.1.1. Data sets

It was necessary to select the most prominent indices in order to gauge the location of countries on each vulnerability scale. The selected indices were Germanwatchs Climate Risk Index (CRI), DARAs Climate Vulnerability Monitor (CVM) and the Global Adaptation Initiatives Global Adaptation Index (GAIN). In addition to these vulnerability indices, the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) was also added upon the suggestion of subject matter expert, Matthew McKinnon (United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and editor of DARA's Climate Vulnerability Monitor). In the case of adaptation funding, the HDI is particularly interesting as it is a more established index (developed by Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq in 1990)8 and might be considered less controversial than the vulnerability indices as a premise for adaptation funding. The HDI was also used to test our assumption that adaptation aid could correspond to development aid. Using the HDI in this way, we would expect to see a high correlation between the HDI and adaptation funding and vulnerability. These indices concerning vulnerability (and development) could thus be correlated with the four multilateral adaptation funds from the Paris Sprint, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), the Adaptation Fund (AF), the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) and Pilot Programme for Climate Resilience (PPCR) as well as the bilateral funding data sets. While there is no suggestion that these funds use these specific indices to assess vulnerability, it is interesting to examine the relationships between funds and indices.

3.1.2. Methods

3.1.2.1. Multilateral funding scatterplot

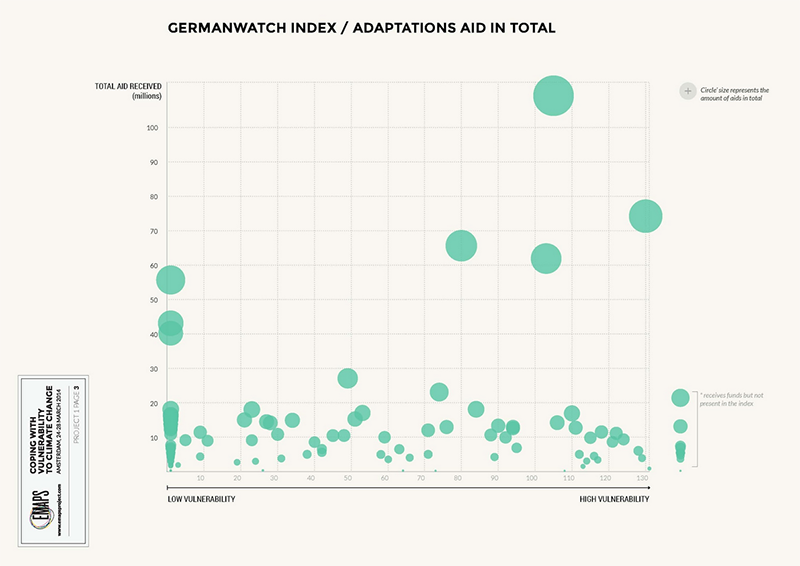

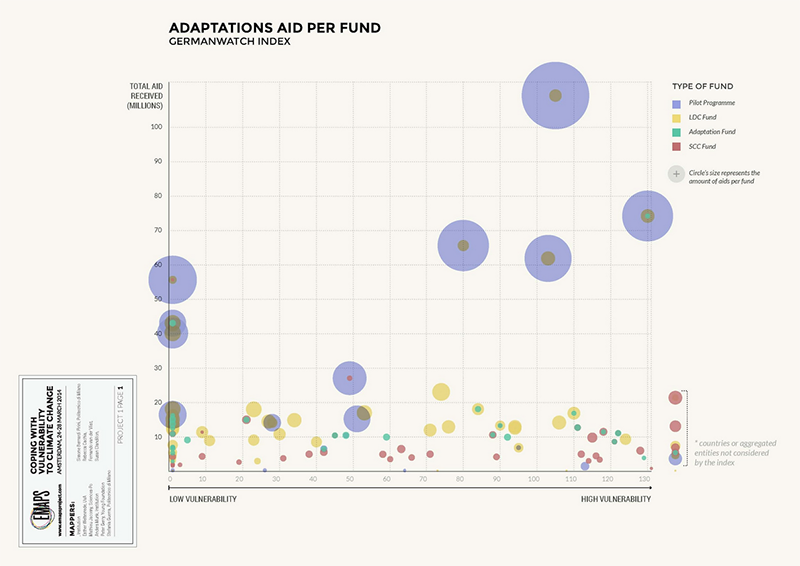

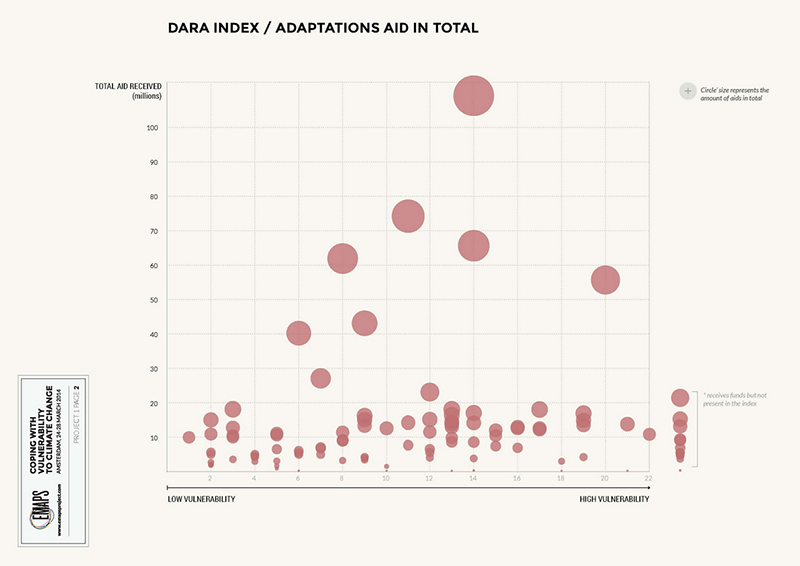

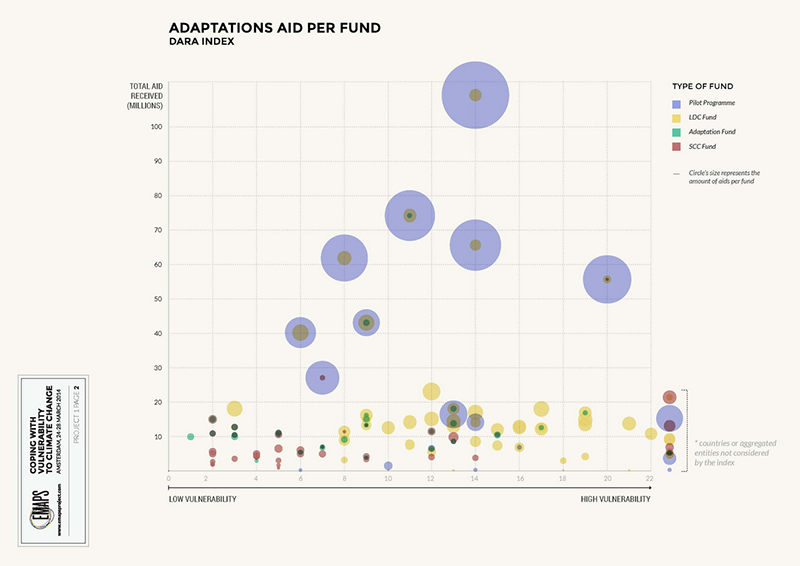

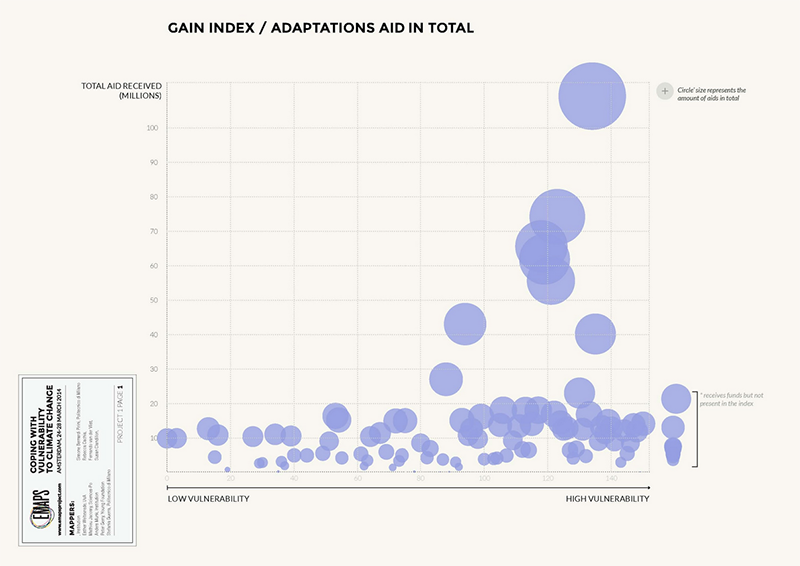

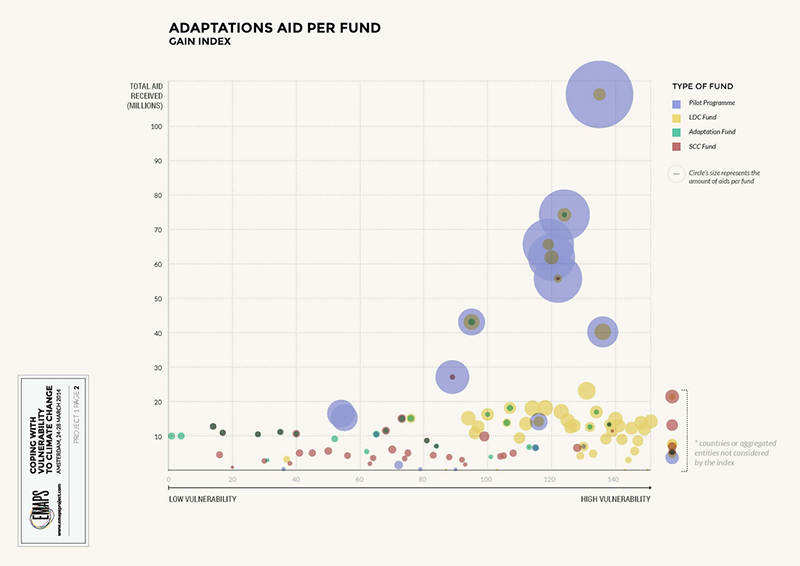

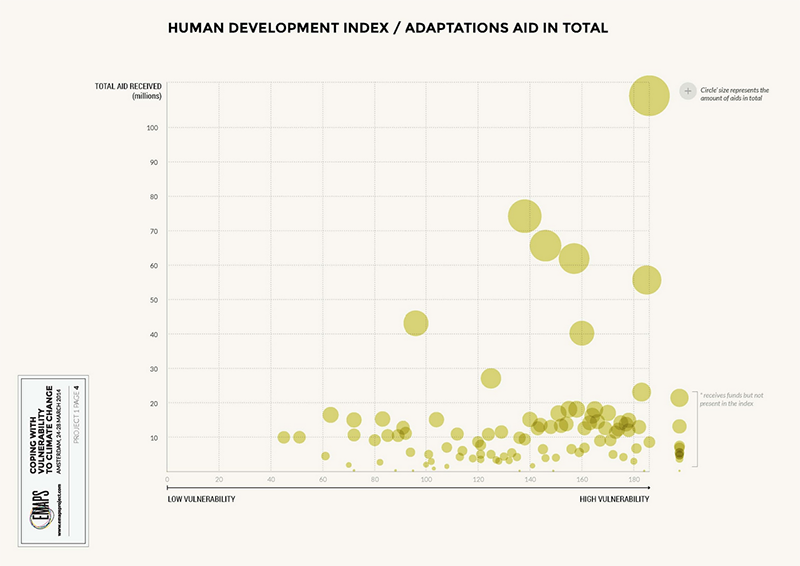

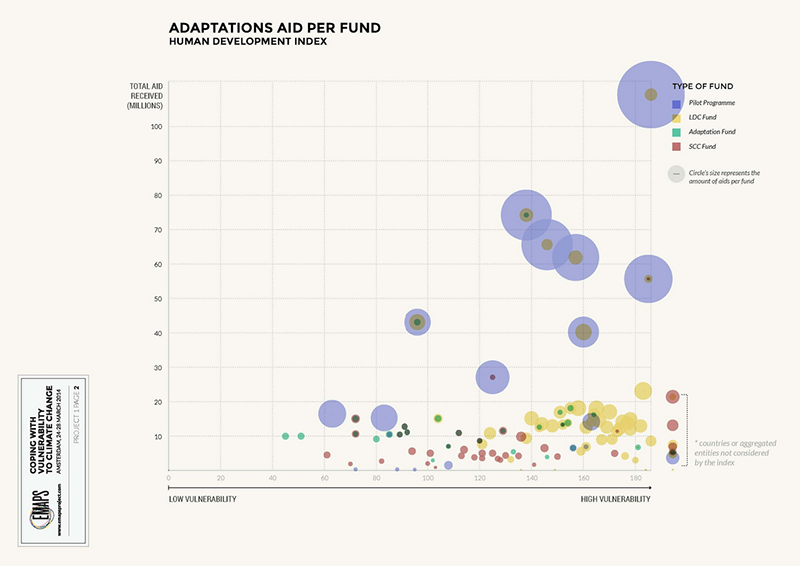

Multilateral funding data from the adaptation funding spreadsheets of the Paris Sprint was plotted on to scatter plot graphs along with data on vulnerability from the selected indices (HDI, GAIN, DARA [CVM] and Germanwatch [CRI]; see Figure 1). Vulnerability is displayed on the x-axis and total funding in millions on the y-axis. The size of the point was used to represent the size of the funding relative to all other funding. For each index two visualisations were created, one showing an aggregate of total adaptation aid per index, and the other showing all four adaptation funds per index. The adaptation funds were coded in different colours for ease of understanding: PPCR in blue, LDC in yellow, AF in green and the SCCF in red. The adaptation funding per index diagrams could then be used to examine how funding was divided proportionally, and how and where each index allocated funding on the vulnerability scale.

Fig. 1a: Multilateral funding scatterplots for Germanwatch, adaptation aids visualised as aggregate.

Fig. 1b: Multilateral funding scatterplots for Germanwatch, adaptation aids separated by fund. (PDF)

Fig. 1c: Multilateral funding scatterplots for DARA, adaptation aids visualised as aggregate.

Fig. 1d: Multilateral funding scatterplots for DARA, adaptation aids separated by fund. (PDF)

Fig. 1e: Multilateral funding scatterplots for GAIN, adaptation aids visualised as aggregate.

Fig. 1f: Multilateral funding scatterplots for GAIN, adaptation aids separated by fund. (PDF)

Fig. 1g: Multilateral funding scatterplots for HDI, adaptation aids visualised as aggregate.

Fig. 1h: Multilateral funding scatterplots for HDI, adaptation aids separated by fund.

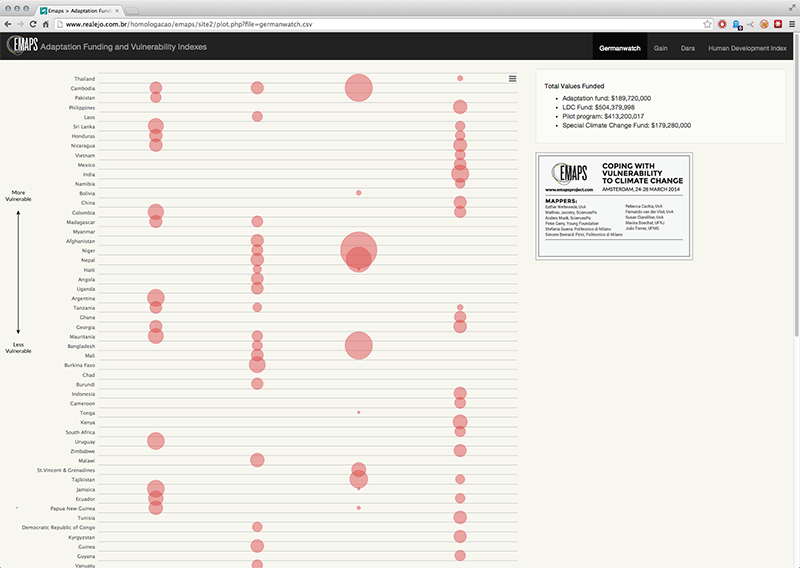

3.1.2.2. Multilateral funding allocation

In addition, an interactive visualisation was also created which combined the data from these scatterplot graphs using HTML and Javascript (Figure 2). A JavaScript library called Highcharts9 was used, and the CSV files for each vulnerability index were fed in. This interactive visualisation features the most vulnerable countries on the y-axis listed from high vulnerability to low vulnerability according to the four indices. Along the x-axis the four adaptation funds were featured. Given the interactive nature of the visualisation, a feature was introduced to toggle between the four funds in order to determine who gave what funding and to whom. The order of the countries would thus change, according to the index selected. A legend was featured in the top right hand corner which also clearly displays the total allocated funding per fund. The red bubbles indicate which indices have given funding to which countries here again the size of the bubble correlates to the size of the funding granted. Hovering over these bubbles also produces a tooltip showing the exact amount of funding given and a normalised percentage of the total amount of money for each fund (Figure 2).

Fig. 2: Screenshot of the interactive chart representing multilateral funding allocations. From top to bottom, countries are arranged by their degree of vulnerability, according to the indices. From left to right, the columns list the Adaptation Fund, LDC Fund, Pilot Programme and Special Climate Change Fund, all of which can be interactively compared and contrasted for Germanwatch, GAIN, DARA, and HDI. (http://www.realejo.com.br/homologacao/emaps/site2/plot.php)

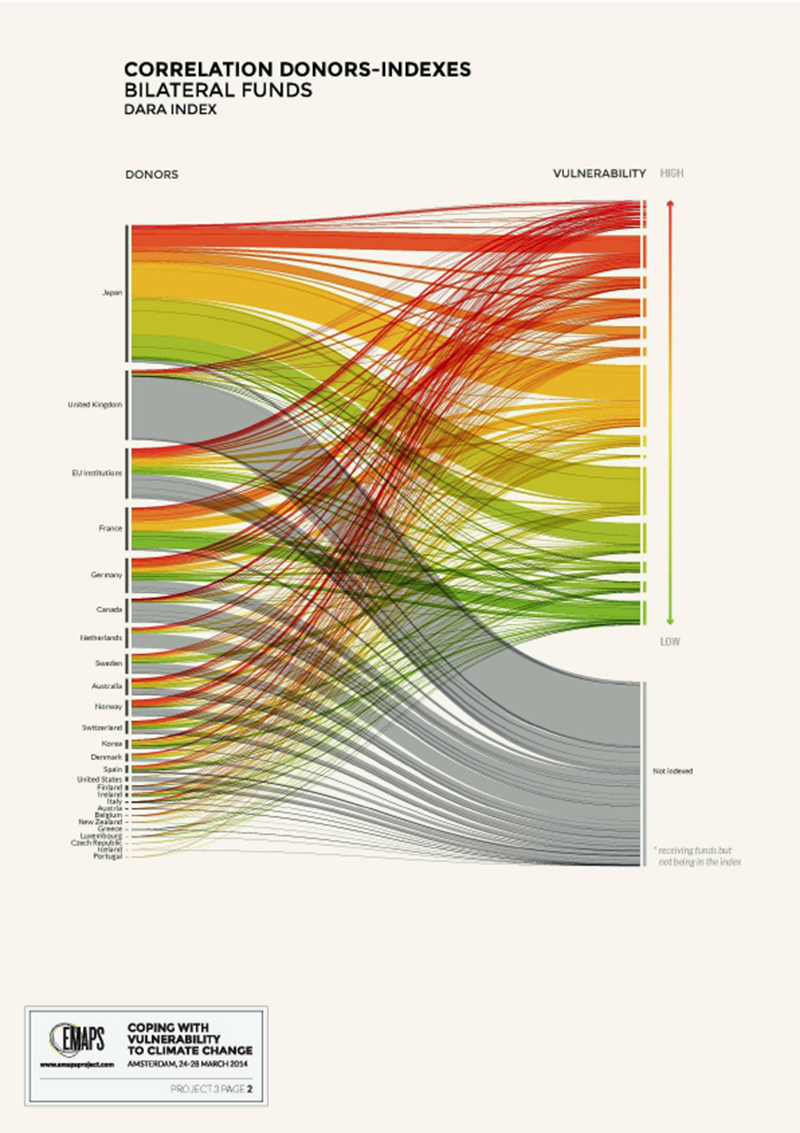

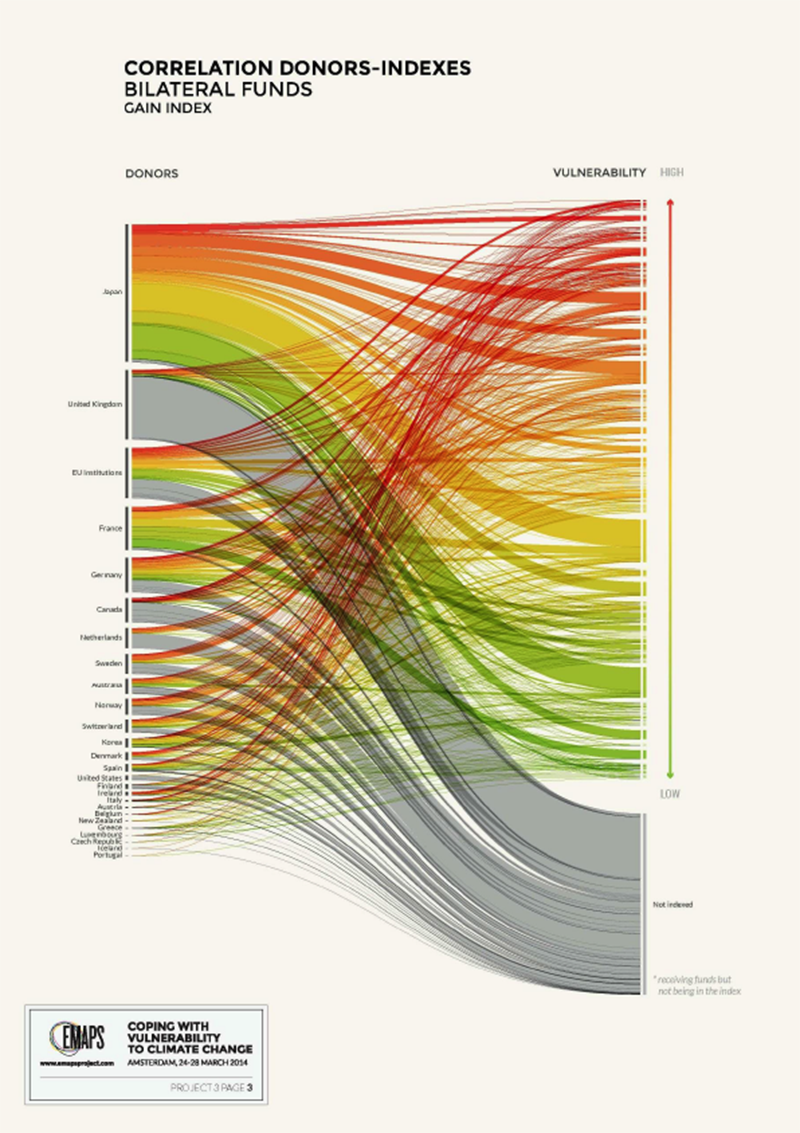

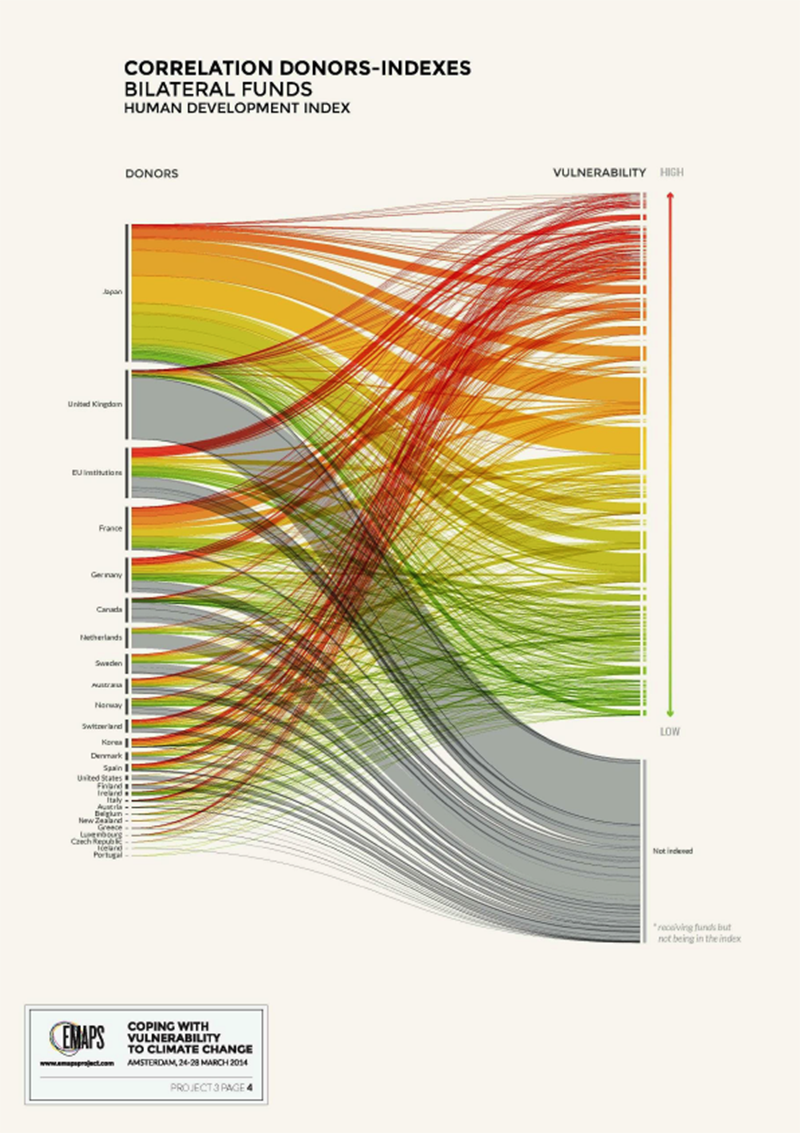

3.1.2.3. Bilateral funding analyses

Data on bilateral funding from the Paris Sprint was also combined with the same four indices, to investigate the relationships between bilateral funding and the indices assessed vulnerability of recipient countries (Figure 3). As before, this data was visualised per index. Here, donors were placed on the left hand side of the visualisation, and recipients on the right. Recipients were ranked in terms of their vulnerability status on a given index. The size of the lines connecting the donor and recipient groupings or countries indicate the amount of funding given and the funding flows. Colour was also used to represent high vulnerability on a temperature scale with red indicating the most vulnerable, and green the least. Notably, not all countries are represented on the index, as some go to country groupings such as small island nations.

Fig. 3a: Bilateral funding allocation for Germanwatch. (PDF)

Fig. 3b: Bilateral funding allocation for DARA. (PDF)

Fig. 3c: Bilateral funding allocation for GAIN. (PDF)

Fig. 3d: Bilateral funding allocation for HDI. (PDF)

3.1.3. Results

3.1.3.1. Multilateral funding analysis

In terms of the multilateral funding visualisations, the relationship between the funds, and vulnerability indices are clearly illustrated. As expected, when adaptation funding is examined in terms of its correlation to the HDIs vulnerability scale then the funding appears to be allocated to the most vulnerable countries, who are often the least developed. Emerging from the visualisations, funding for the Germanwatch index appears well distributed among the recipient countries, although the largest amounts of funding are allocated to countries deemed highly vulnerable. For the DARA index, it is countries located in the middle of the vulnerability index who get the most funding. However, when we examine the GAIN index we discover that the funding has shifted down to the countries who score highly for vulnerability. The patterns in adaptation funding appear similar between the GAIN index and the HDI suggesting that the GAIN index focuses on countries that are both highly vulnerable and least developed. In this case, the LDC and PPCR funds give most support to high vulnerability countries.

3.1.3.2. Interactive graph

The interactive graph provides novel ways to investigate the alignment between choice and priorities for adaptation funding and vulnerability indexing criteria. The user interface allows for four different viewpoints and the zoom function allows for the ease of interpretation, especially in areas of clustering. (As the graph can be fed with real time data, it brings us closer to an idea of cartographic monitoring.) Per index the most significant findings can be extracted through toggling the relevant index tabs. For the Germanwatch index, the PPCR uses its large funding budget ($ 413,200,017) across the vulnerability scale, but grants large amounts of funding to a select number of countries on the scale be they high or low vulnerability countries. Regarding the GAIN index, the key finding relates to the LDC fund which mostly allocates funding to high vulnerability countries. These funding amounts are small but evenly distributed. For the DARA index, the PPCR stands out as having distributed the greatest amount of funding across the least countries and these extend along the vulnerability index. This appears similar to the Germanwatch index. With the HDI however, it is the LDC fund which stands out through its allocation of funds in small quantities to many high and medium vulnerability nations. In this case the use of LDC funding correlates in both the GAIN index and the HDI. Thus suggesting that there is high correlation between countries that are deemed most vulnerable and least developed.

3.1.3.3. Bilateral funding analysis

In terms of the bilateral findings, the visualisations show that most countries providing bilateral aid have a fairly balanced approach, and grant aid to a number of nations and nation groupings such as the Caribbean nations. In terms of the most significant findings per index, bilateral funding data compared with the Germanwatch index indicates that Japan is granting the most adaptation funding, but this is mostly to countries ranking as having medium or low vulnerability. This suggests that the granting of funding does not necessarily just relate to the vulnerability of the country, and may also relate to the geopolitical interests of the donor. The DARA index however, indicates that many donor countries are donating small amounts of funding, but frequently to high vulnerability countries. The GAIN index and HDI also indicate this trend, leading to the assumption that vulnerability funding may be development aid by another name.

3.2. Web corpus analysis

The second subproject studied the users and uses of the vulnerability indices within websites. The aim is to map out the mentions of the indices within a specific Web corpus. This subproject discusses the following questions:

- Which website cites which index?

- In what context are the indices cited?

3.2.1. Data sets

For this subproject we used two data sets. The first dataset contains a list of indices and the second one contains a corpus of different websites. The list of the indices is an expanded list of the four indices that were used at the first subproject, funding. The total list of indices can be found in Table 1 below. Not only did we include vulnerability indices, we also added economic models such as DICE and also other indices such as the Human Development Index (HDI). The reason that we added these indices is because these indices are also used in a climate adaptation context. Furthermore, these indices are used in competition with one another.10 The HDI is expected to be the most used index since it is one of the oldest indices and because it covers a broad field within climate change.11

The second data set consists out of 725 climate change websites. The Web corpus we used was retrieved from a previous project during the EMAPS Paris Sprint. These websites have been ordered according to three categories. First the websites have been defined according to the actor type to either individual, international institutions, academic institutions, online communities, governments, events, media, association, fund, bank, business,religious or undefined. Secondly, the websites have been categorised whether they are specialised on adaptation or not (the vast majority is not). Finally we categorised the websites according to their geographical territory. This refers to the country or region that the organization of website is dedicated to. If the organization did not dedicate its focus towards any country or region it is listed as undefined.

Table 1. List of indices, arranged by type.

| Index Name | Abbreviation | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Climate and Regional Economics of Developments vulnerability index | CRED | Vulnerability Index |

| NatureServe Climate Change Vulnerability Index | CCVI | Vulnerability Index |

| Environmental Vulnerability Index | EVI | Vulnerability Index |

| Climate Vulnerability Monitor | CVM | Vulnerability Index |

| Global Adaptation Index | GAIN | Vulnerability Index |

| Social Vulnerability Index | SVI | Vulnerability Index |

| Global Climate Risk Index | CRI | Vulnerability Index |

| Climate Change Performance Index | CCPI | Vulnerability Index |

| Dynamic Integrated Climate Change | DICE | Economic Model |

| Regional Integrated Climate and the Economy | RICE | Economic Model |

| Climate Framework for Uncertainty, Negotiation and Distribution | FUND | Economic Model |

| Model for Evaluating the Regional and Global Effects | MERGE | Economic Model |

| Human Development Index | HDI | Other |

| Multidimensional poverty index | MPI | Other |

| Human Poverty Index | HPI | Other |

| Gender-related Development Index | GDI | Other |

| Gender Inequality Index | GII | Other |

| Economic Vulnerability Index | ECVI | Other |

3.2.2. Methods

We are aiming to map out the mentions of the indices on the websites. In order to do so, we needed to make them queryable. For each index we have made two sets of queries: one designed for a general corpus and one for a climate specific corpus. Although this subproject has a climate specific corpus (websites of climate adaptation NGOs), the other set of queries will be used in some of the other subprojects. The main difference between the two sets of queries is that the queries for a not climate specific corpus contains the words climate or climate change. This way we would only retrieve a result if the index is used in the context of climate change. Besides English the queries are also designed for a French and Spanish corpus. Most of the indices are used in their original English names, while some of them have a specific French or Spanish name. We checked this by looking at the different language versions of Wikipedia and the United Nations website. We looked if one of these websites use the indices in Spanish or French. If so, we added the Spanish or French name of the index to the query. Furthermore, we have designed a general vulnerability assessment (VASS) query which does not refer to any index but to climate change adaptation in general (Table 2).

Table 2. Query design overview.

| Index name | General corpus query | Climate-specific corpus query |

|---|---|---|

| CRED | (vi cred OR vi-cred OR cred) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) AND (index OR indice OR indicateur OR índice) | vi cred OR vi-cred OR cred |

| CCVI | Climate Change Vulnerability Index | Climate Change Vulnerability Index |

| EVI | Environmental Vulnerability Index OR El Indice de Vulnerabilidad Ambien | Environmental Vulnerability Index OR El Indice de Vulnerabilidad Ambien |

| CVM | Climate Vulnerability Monitor | Climate Vulnerability Monitor |

| GAIN | Global Adaptation Index | Global Adaptation Index |

| SVI | Social Vulnerability Index | Social Vulnerability Index |

| CRI | Global Climate Risk Index | Global Climate Risk Index |

| CCPI | Climate Change Performance Index | Climate Change Performance Index |

| DICE | (DICE econ* OR DICE model OR DICE économique* OR modèle DICE OR DICE económico OR modelo DICE) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | DICE econ* OR DICE model OR DICE économique* OR modèle DICE OR DICE económico OR modelo DICE |

| RICE | (RICE econ* OR RICE model OR RICE économique* OR modèle RICE OR RICE económico OR modelo RICE) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | RICE econ* OR RICE model OR RICE économique* OR modèle RICE OR RICE económico OR modelo RICE |

| FUND | Climate Framework for Uncertainty, Negotiation and Distribution AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | Climate Framework for Uncertainty, Negotiation and Distribution |

| MERGE | Model for Evaluating the Regional and Global Effects AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | Model for Evaluating the Regional and Global Effects |

| HDI | (Human Development Index OR Indice de développement humain OR Índice de Desarrollo Humano) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | Human Development Index OR Indice de développement humain OR Índice de Desarrollo Humano |

| MPI | (Multidimensional Poverty Index OR Indice de pauvreté multidimensionnelle OR indice de pobreza multidimensional) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | Multidimensional Poverty Index OR Indice de pauvreté multidimensionnelle OR indice de pobreza multidimensional |

| HPI | (Human Poverty Index OR Indicateur de pauvreté OR Índice de pobreza) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | Human Poverty Index OR Indicateur de pauvreté OR Índice de pobreza |

| GDI | (Gender-related Development Index OR gender related development index OR indice de développement selon le genre OR Índice de desarrollo humano relativo al género) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | (Gender-related Development Index OR gender related development index OR indice de développement selon le genre OR Índice de desarrollo humano relativo al género) |

| GII | (Gender Inequality Index OR Indice d'inégalités de genre OR Indice d'inégalité de genre OR Indice d'inégalité selon le genre OR Índice de desarrollo humano relativo al género OR Índice de Desigualdad de Género) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | Gender Inequality Index OR Indice d'inégalités de genre OR Indice d'inégalité de genre OR Indice d'inégalité selon le genre OR Índice de desarrollo humano relativo al género OR Índice de Desigualdad de Género |

| ECVI | (Economic Vulnerability Index OR indice de vulnerabilidad economica OR indice de vulnérabilité économique OR indicateur de vulnérabilité économique) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | Economic Vulnerability Index OR indice de vulnerabilidad economica OR indice de vulnérabilité économique OR indicateur de vulnérabilité économique |

| VASS | (vulnerability assessment OR vulnerability index* OR vulnerability indic* OR vulnerability monitor OR indic* de vuln* OR évaluation de la vuln* OR evaluation de la vuln* OR indic* de la vulnerabilidad OR evalua* de la vulnerabilidad) AND (climate OR climat OR clima) | vulnerability assessment OR vulnerability index* OR vulnerability indic* OR vulnerability monitor OR indic* de vuln* OR évaluation de la vuln* OR evaluation de la vuln* OR indic* de la vulnerabilidad OR evalua* de la vulnerabilidad |

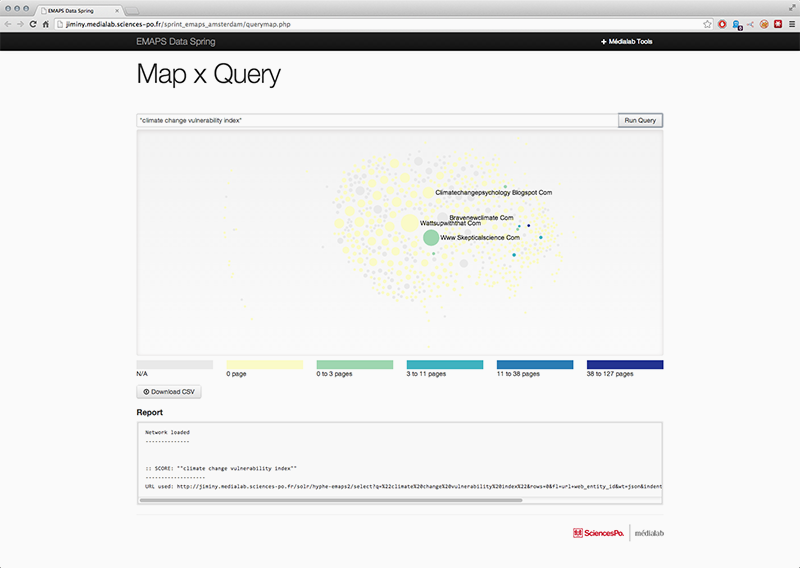

We have loaded the website corpus into several tools on the Sciences Po Médialab Web domain, where they could be queried and mapped in real-time12. Here we have created several (interactive) visualisations and tools in order to explore the data. Figure 4 is a screenshot from the Map x Query visualisation (Figure 4). The websites are placed according to their link relations and sized according to the number of pages the website is mentioned. At the top of the page you can enter a query and the colors of the map refer to the number of pages that a website mentions that query. This tool can be used to explore the websites. By querying the indices one can see how many times each website uses that index. The screenshot shows the query for the Climate Change Vulnerability Index (CCVI), and as the map shows, the index is only mentioned by very few websites.

Fig. 4: Map x Query screenshot for [climate change vulnerability index] (http://jiminy.medialab.sciences-po.fr/sprint_emaps_amsterdam/querymap.php).

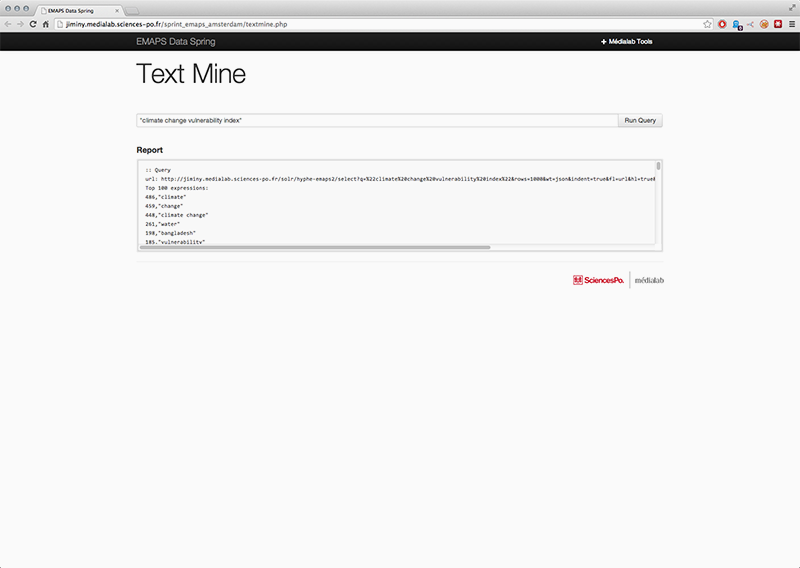

Figure 5 is a screenshot of the top n-gram from the Text Mine tool where it is possible to query the websites and retrieve words which co-appear with the query. When querying the CCVI it becomes clear that it has been used in the same context as the keyword water. We took the top 10 keywords that appeared with each index and put them in a final list of keywords which are presented in figure 4.

Fig. 5: Text Mine screenshot of the top n-gram for [climate change vulnerability index] (http://jiminy.medialab.sciences-po.fr/sprint_emaps_amsterdam/textmine.php).

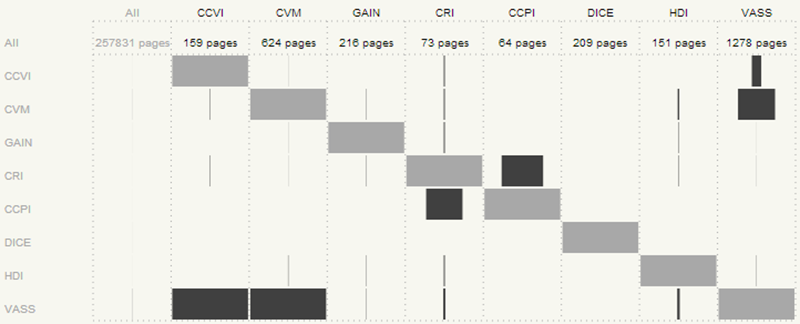

Figure 6 shows a visualisation of the number of pages each index is mentioned in total and the number of times other indices appear on those same pages. As the figure shows, only the Climate Risk Index (CRI) and the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) appear on the same page a significant number of times. Most probably, this is because both of these indices are made by Germanwatch. VASS refers to a generic query for vulnerability assessment and therefor it co-appears with the indices.

Fig. 6: Cross-checked coappearance of indices on the same page.

3.2.3. Results

Figure 7 shows a screenshot from the Cross Count analysis tool. On the most left column are keywords which refer to climate change. The top row represents the different indices. Between those two elements the number of pages that this index is mentioned with the specific keyword is represented. For example, GAIN is mentioned on 216 pages in total. The bars in the GAIN column represent how many of those 216 pages contain the specific keywords which can be found in the left column. This means that the keywords relating to adaptation (ADAP in the column) is visible on all the pages that mention GAIN, while only a few of those pages mention the keyword development. The two indices from Germanwatch, CRI and CCPI are almost identical. This means that in these two indices are mentioned together in any context. The GAIN index is the most visible among the vulnerability indices. It is interesting to see whenever the GAIN index is the only index mentioned of those four. This is the case with the keywords freedom and readiness. This could refer to a somewhat progressive context.

Fig. 7: Cross Count matrix of queries and indices (http://jiminy.medialab.sciences-po.fr/sprint_emaps_amsterdam/crosscount.php).

By querying different keywords into the pages that mention the indices, we were able to get a better understanding of the contexts these indices are used. The different vulnerability indices do not share the same context (with exception of the CRI and CCPI since they are both from Germanwatch). They all seem to have their own space on the Web corpus. We do see some similarities between the other indices. The DICE and HDI seem to appear at the same contexts. The keywords climate change and the queries regarding to adaptation (ADAP in the figure) are the two contexts that are shared with most of the indices. The only index that is mentioned in the context of climate scepticism (SCEP) is DICE, while the other indices are not. This suggest that vulnerability assessment is still such a specialised language that the sceptics are not picking it up.

3.3. UNFCCC national communications documents

A corpus of National Communication (NC) documents was compiled in order to determine the frequency of use of the indices in national contexts. The NCs are reports that are produced at a national level and then submitted to the UNFCCC by the country in question. They largely contain information regarding strategies being implemented to tackle the challenge posed by climate change at a national level.13 Through the analysis of the NCs, we aimed to answer the following analytical questions:

- Which countries are citing which indices in their NCs?

- When are different indices cited in these documents?

3.3.1. Dataset and methods

By searching through the UNFCCCs online Library and Documentation Centre, a total of 492 NCs were retrieved spanning a quasi twenty-year period from 1994 to 2014.14 The number of documents and time range signify the complete amount of NCs that are available to the public through the UNFCCCs online Library and Documentation Centre, which provides links to PDF versions of the NCs. Scraping the website for the PDF documents was achieved by using the Digital Methods Initiatives Link Ripper tool15 and the DownThemAll Firefox browser plug-in.16 Specifically, by inputting the URLs to the Web pages containing the NCs, we captured the links to the PDF versions using the Link Ripper tool and tabulated them in a spreadsheet.17 Due to occasional inconsistencies in the output of the Link Ripper tool, some of the links needed to be retrieved manually and then added to the same spreadsheet. The list of URLs was then saved as a text file that was then opened in the Firefox browser, which enabled us to use the DownThemAll plugin to download the PDF versions of the NCs.

The PDFs were retrieved to be queried using the expanded list of indices also used in the Web Corpus dataset (Table 3) and the climate-specific list of queries (Table 4) in order to gauge the resonance and frequency of mentions of the indices across the NCs. The climate-specific queries were adapted from the general queries used in the Web Corpus and Google Scholar datasets in order to remove parts of the queries such as climate that would be superfluous in the NCs as they are already climate-specific documents. An obstacle that needed to be overcome, however, was the fact that a majority of the NCs were scanned documents in which the text was not recognisable and therefore those documents could not be searched for words or phrases. To counteract this problem all the NCs were batch processed for Optical Character Recognition (OCR or text recognition) in Adobe Acrobat. Once the entire dataset was rendered readable, the climate-specific set of queries were searched for in English, French and Spanish. In order to semi-automate the process of searching through the 492 NCs, the querying was carried out using egrep18 a command-line utility which enables the researcher to search through lines in plain-text files using a query so as to find matches to that query (which is a pattern) across the text files. The PDFs were therefore first converted into plain text files19 and then queried. The results of these grep searches showed which indices were used, by which country and in which year. These results were tabulated in a spreadsheet for further analysis.20

3.3.2. Results

A total of 83 matches for names of indices were found across the 492 NCs we analysed. In terms of the indices in which the highest frequency of occurrence (more than three occurrences) was discovered, this translates to:

Table 3. Number of occurrences for the four most cited indices in the corpus of 492 National Communications documents retrieved from the UNFCCC website.

| Index name | Developer | Number of occurrences |

|---|---|---|

| Human Development Index (HDI) | United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) | 49 |

| Human Poverty Index (HPI) | United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) | 6 |

| Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) | United States Geological Survey (USGS) | 6 |

| Environmental Vulnerability Index (EVI) | United Nations Environment Programme & South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (UNEP/SOPAC) | 4 |

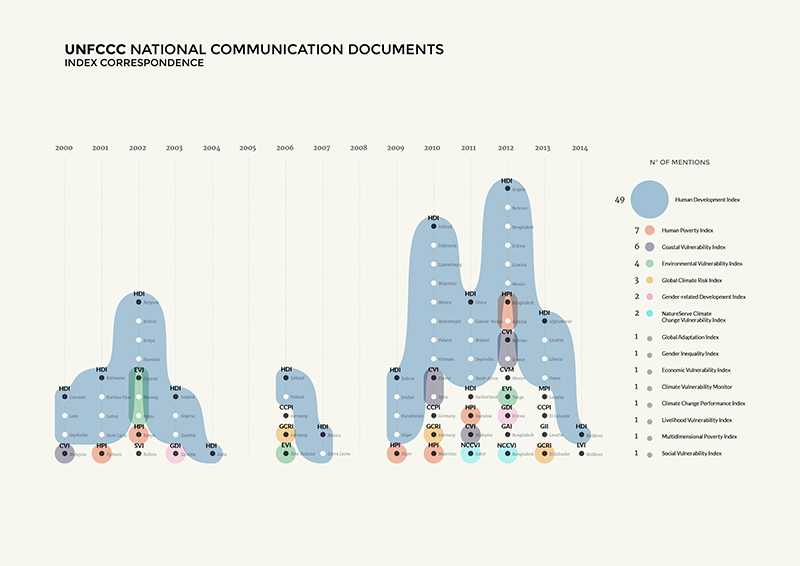

Some indices resonated more than others, which is especially true of the indices developed by the United Nations (UN): the HDI, HPI and EVI. As a composite index that measures development based on a number of indicators (including life expectancy, educational attainment and income), the HDI is by far the most cited index. Other than indices developed by the UN, the only index that was cited more than three times was the CVI, which was an index previously unknown to the researchers and which was only discovered through the process of querying the NCs. Therefore, of the original vulnerability indices queried, only the EVI resonated more than three times. Germanwatchs Global Climate Risk Index and NatureServe s Climate Change Vulnerability Index only occurred three times and twice respectively over the entire dataset (Figure 8).

The NCs that most cited indices were those outputted by Bangladesh, Gambia, Germany and Mexico (with four occurrences of indices each), and Iceland and Lesotho (with three occurrences of indices each; see Table 4). These countries used the following indices:

Table 4. Countries that most frequently cited indices (more than three times) in addition to the indices that were cited and the publication year of the document they were cited in.

| Country | Index name |

|---|---|

| Bangladesh | Global Adaptation Index or GAIN (2012) developed by the Global Adaptation Initiative Human Development Index (2012) developed by the UNDP Human Poverty Index (2012) developed by the UNDP NatureServe Climate Change Vulnerability Index (2012) developed by NatureServe |

| Gambia | Gender-related Development Index (2003) developed by the UNDP Human Development Index (2003; 2012) developed by the UNDP Human Poverty Index (2012) developed by the UNDP |

| Germany | Climate Change Performance Index (2006; 2010) developed by Germanwatch Global Climate Risk Index (2006; 2010) developed by Germanwatch |

| Iceland | Human Development Index (2003; 2006; 2010) developed by the UNDP |

| Lesotho | Gender Inequality Index (2013) developed by the UNDP Human Development Index (2013) developed by the UNDP Multidimensional Poverty Index (2013) developed by the UNDP |

| Mexico | Climate Vulnerability Monitor (2012) developed by DARA Human Development Index (2007; 2010; 2012) developed by the UNDP |

Following the countries that most cited indices illuminates the marginal indices that also occurred across the dataset. More indices developed by the UNDP are discovered, including the Gender Inequality Index (used by Lesotho in 2013) and its predecessor the Gender-related Development Index (used by Gambia in 2003), in addition to the Multidimensional Poverty Index (used by Lesotho in 2013). Furthermore, the GAIN index (used by Bangladesh in 2012), DARAs Climate Vulnerability Monitor (used by Mexico in 2012), and Germanwatchs Climate Change Performance Index and Global Climate Risk Index (used by Germany in 2006 and 2010) appear as marginally used indices that are specific to the issues of adaptation and vulnerability to climate change. Interestingly, Germanwatchs two indices were only cited by Germany and, of the indices queried, those were also the only indices ever cited by Germany in its NCs.

Fig. 8: Overview of correspondences between countries and index mentions in UNFCCC national communications documents over the years, 20002014. (PDF)

The high occurrence of citations of the HDI in a context of national reporting on strategies to tackle the challenge posed by climate change leads to a hypothesis regarding the use and abuse of both vulnerability and development indices by the countries in question. Taking a closer look at the ranking of a particular country within the index and in the year in question is quite telling. For example, when Bangladesh cited the HDI in 2012, it was ranked at 146 out of 186 countries within the index, signifying a very low level of development.21 Furthermore, in the GAIN index that summarises a countrys vulnerability and readiness to combat climate change challenges in order to facilitate the prioritization of investment in that country, Bangladesh ranked at 145 out of 177 countries, signifying a high level of vulnerability, a low level of readiness to tackle climate change challenges and therefore in great need of investment.22 Another case in point is that of Mexicos use of DARAs Climate Vulnerability Monitor (CVM) in 2012 the only occurrence of the CVM across the dataset when it was classified as having moderate/high vulnerability on a five-point scale (low/moderate/high/severe/acute) in addition to being classified as having increasing vulnerability (rather than stable or decreasing vulnerability).23

Due to the time constraints experienced during the EMAPs Amsterdam Sprint, delving deeper into an analysis of the ranking of each country on the cited indices is beyond the scope of this paper. However, testing this hypothesis of the use and abuse of indices by the countries that cite the indices in order to establish a potential correlation between index rankings and the countries citation of indices would be an interesting next step to take. Moreover, analysing the more specific context of citation within each countrys report would also be valuable in establishing a further correlation between the country, the index and the specific issues at hand, be them issues of forestry, fisheries, vulnerable communities and so forth.

3.4. Google Scholar analysis

This subproject studied how the indices are used within the scientific literature. We analysed which publications cites which indices. The aim of the subproject was to answer the following questions:

- How do indices rise and fall within the scientific literature?

- What are the top indices per journal?

- In which context are the indices cited in the scientific literature?

3.4.1. Data set and methods

The data set we used for this projects are all the indexed publications on Google Scholar. By using Publish or Perish24 we were able to query the indices and retrieve results ordered by publication date and the different journals. This way we could see the number of times a certain index was cited over time. Additionally, we were able to link the different indices to the different journals. For our query design we used the general corpus queries. This way we would only retrieve a result when one of the indices was cited in a climate change/ adaptation context. Unfortunately we could only scrape up to a thousand results on Google Scholar per index. Only four indices have more: HDI (46.600), Human Poverty Index (HPI) (4.840), DICE (4.840) and the Gender Related Development Index (1.150)

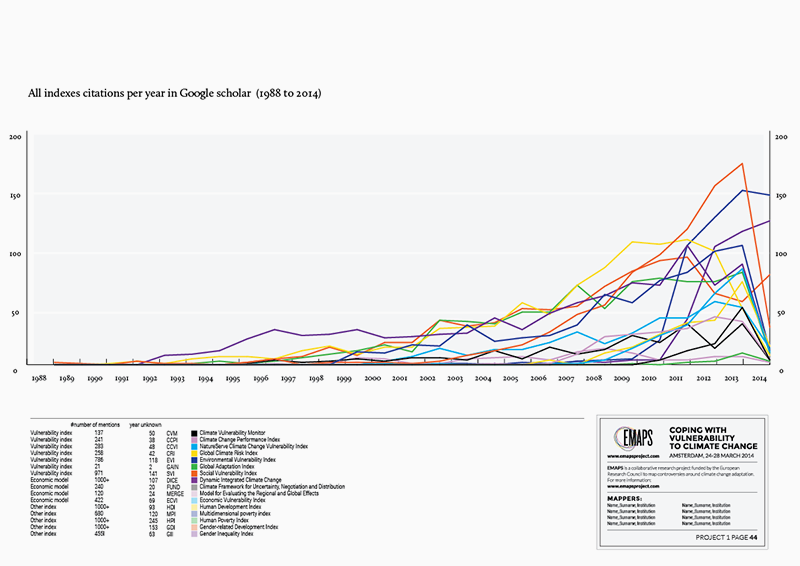

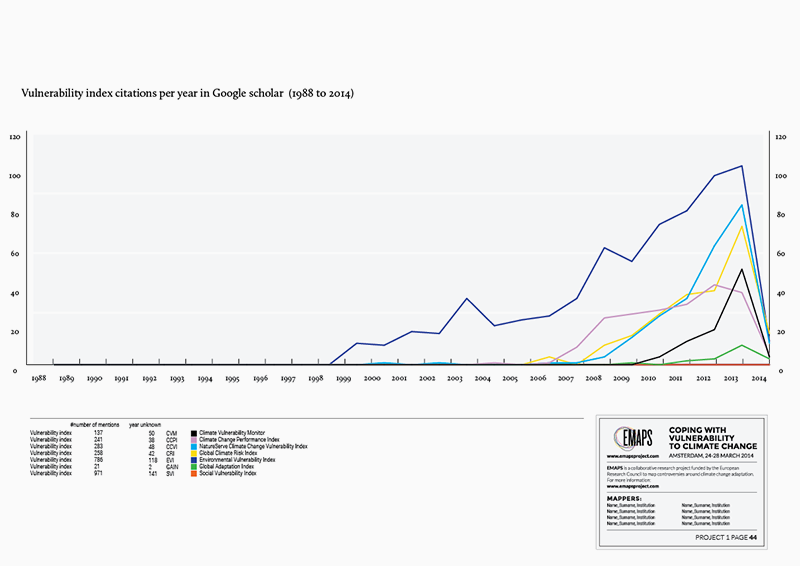

Fig. 9: Index citations per year in Google Scholar, 19882014. Most of the indices show a steady increase over the past years. This could refer to the increasing attention towards climate adaptation. This is confirmed when looking at the vulnerability indices which increased greatly since 2010.

Fig. 10: Vulnerability indices per year in Google Scholar, 19882014. In this set, the EVI is the most popular index. It is also the only index which is visible before 2006. DARAs Climate Vulnerability Monitor (CVM) and Tyndall Centres Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) are the least popular indices.

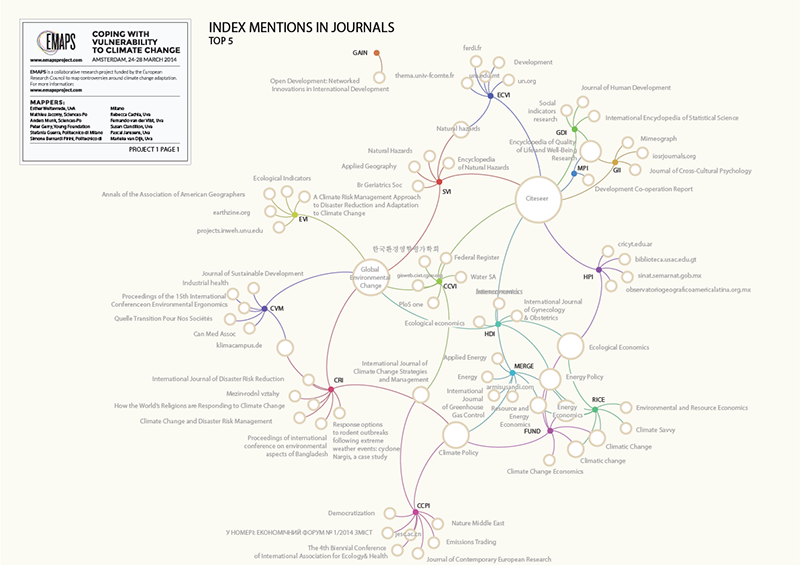

Fig. 11: Network graph for the top-5 mentioned indices in journals in Google Scholar. This network graph tells us that there is a clear cluster of the economic models: RICE, FUND and MERGE. The vulnerability indices are all mentioned in the Global Environmental Change journal. (PDF)

3.4.2. Results

There seems to be a rise and not a fall of the vulnerability indices. While being one of the most cited indices, the HDI has been dropping since 2009. Not many journals cite several indices. The ones that cite the most indices are the journal Global Environmental Change, Siteseer and Climate Policy. The latter one is connecting the vulnerability indices cluster with the economic ones. However these two types of indices do seem to form their own cluster and therefore it seems that there is no indication that the economic models and the vulnerability models are in competition with one another in the scientific literature.

3.5. News sphere analysis

The objective of this subproject has been to understand how and when the different indices are used within the news media. The subproject was set up to answer the following questions:

- When do the indices catch the attention of the media?

- Do attention cycles coincide with press releases, or do they seem to be driven by other events as well?

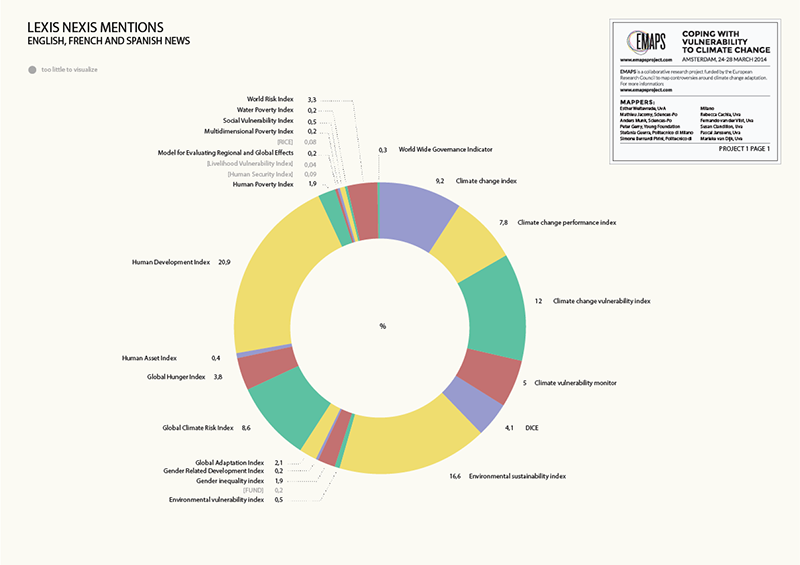

The data set we used for this project is the news archive of LexisNexis. More specifically, we included all the English, Spanish and French news. We queried the LexisNexis database, using the query design for a general (not climate specific) corpus. We retrieved the results but we could not use this data for the questions we had within the time we had. However, for now, we can show an overall overview of the number of times each index was cited within the news media.

It is hard to make any meaningful conclusions about this, as figure 12 presents us only with an initial and general overview. Moreover, the news articles date back to 1968, and since many indices did not exist at that time it would be an unfair comparison. However, in this chart, the Climate Vulnerability Monitor (CVM) is cited most often, although surprisingly this index has not been very present in the analyses of the other data sets. Further studies could investigate why the CVM index is more present within this data set rather than within the others.

Fig. 12: Initial results for index mentions analysis in English, French and Spanish news sources on LexisNexis. (PDF)

5. Discussion and suggestions for further research

During the Amsterdam Sprint we studied uses and users of several vulnerability indices. Five sub-projects contributed to our main research question: which particular climate change vulnerability indices and/or indicators that are relevant in the selected decision-making contexts are competing and where can we locate this competition? The five different sub-projects studied the use of the indices within various data sets: adaptation funding programmes, a Web corpus, scientific literature, the UNFCCC national communication documents and news media. Our main finding is that the different categories of indices (vulnerability, economic and other) are not competing with each other within the same space. We found no significant mention of these different indices within the same context. For the scientific literature this means that the indices are not mentioned significantly within the same journals. In the Web corpus there was no indication that the three different categories of indices appeared within the same contexts. However, there is an indication for competition among the indices which are from the same category. This is especially visible within the network we presented of the journals and cited indices. Each category of indices does seem to have its own space within the scientific literature (i.e. they are cited by the same journals). However, this does not account for the contexts within which the indices are mentioned within the Web corpus. It seems that the vulnerability indices each have a different context that they are mentioned in. This would indicate that competition only occurs within specific spheres, such as the scientific literature, and not within others such as the Web corpus.

As shown by our results, the dissemination and use of a particular index in place of other indices is at the behest of the particular country (or other actor) in question. As composites of specific indicators of development and/or vulnerability, indices are highly dependent on the specific local context and open the floor to discussions about how the local is represented within national indices or to what extent the accuracy of local vulnerability is preserved or lost within the composite of national indices. Therefore, a countrys choice to use a particular index in place of other indices is of interest. For example, the fact that the only indices used by Germany in its national communications to the UNFCCC are those produced by Germanwatch (and that those same indices are not used by any other country within that dataset) makes a case for furthering the discussion into establishing a clearer rationale for an actors use of an index. Furthermore, investigating correlations between a countrys use of an index in contexts such as applications for funding, national reports to the UNFCCC, and the news sphere, and that countrys ranking on the index in addition to the funding that country receives, could lead to potentially discussing the question: do countries cite certain indices in order to make a better case for increased foreign investment, aid and/or other forms of bilateral and multilateral funding within that country? In light of establishing that there is a strong correlation between adaptation funding and development aid, through the results relating to multilateral funding and the Human Development Index (HDI), a case can be made for the issue of the controversiality of adaptation funding. Conflating adaptation aid with development aid or allocating adaptation aid on the basis of development indices and/or indicators in order to allocate funding to countries somehow deemed more deserving, lessens the moral contestation or potential controversy surrounding the allocation of adaptation aid on the basis of a measurement of vulnerability to climate change.

Therefore, a countrys ranking on an index matters, both from the funding donors point of view in addition to the countrys choice to associate itself with a particular index. For example, the fact that in its bilateral funding allocation, Japan gives a large amount of funds to medium-low vulnerability countries raises the question of whether this is the case because of certain geopolitical interests Japan might have. However, it also highlights the consideration that a countrys ranking on an index and the measurement of indicators matters because funding might not be given to the most vulnerable and/or poorest or least developed countries due to a countrys poor performance in certain indicators of the stability of governance and infrastructure within that country. Mapping the correlation between the use of vulnerability indices in the allocation of funding together with the stability of governance of the recipient countries would add another facet to determining the use of vulnerability and development indices.

The project gives several starting points for further research. Each sub-project opens up new questions. We explored the relation between the ranking of countries in the vulnerability indices and the amount of funding going to these countries. Further studies could be conducted regarding the way these funding programmes actually use the indices. The Web corpus could be more specific. With this we mean that the set of websites should be expanded. Also, the websites could be better categorised in order to see in what context, for example, the NGO websites are using the indices. Moreover, delving deeper into the research conducted using the UNFCCCs national communication documents by analysing the ranking of each country on the cited indices in addition to the specific issues raised in conjunction with the indices within those reports could test the hypothesis of the use and abuse of indices by those countries. This could be supplemented with correlation analyses of country rankings on vulnerability indices together with indicators of governance stability and subsequent funding allocation. Finally, as mentioned in the previous section, the data of the news media sub-project further explored. Why is the Climate Vulnerability Monitor more present in this data set than in the other ones?

6. Footnotes

1. EMAPS is a three-year collaborative research project funded by the European Commission in the Community Research and Development Information Service (CORDIS) FP7 Science in Society programme. The Amsterdam Sprint is the second in a series of four sprints dedicated to mapping climate change controversies. See also: <http://www.emapsproject.com/blog/about> and <http://cordis.europa.eu/fp7/sis/home_en.html>.

2. International Negotiations on Climate Change Adaptation, hosted by the Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques (Sciences Po) in Paris from January 6th to 10th, 2014. See also: <http://www.emapsproject.com/blog/archives/2244> and <http://www.emapsproject.com/blog/archives/2348>.

3. Coping with Vulnerability to Climate Change: Adaptation, its Limits and Post-Adaptation Mechanisms, hosted by the University of Amsterdam (UvA) and Digital Methods Initiative (DMI) from March 24th to 28th, 2014. See also: <http://www.emapsproject.com/blog/archives/2326> and <https://wiki.digitalmethods.net/Dmi/VulnerabilityClimateChange<.

4. In a report by the International Risk Governance Council (IRGC), risk management is defined as [t]he creation and evaluation of options for initiating or changing human activities or (natural and artificial) structures with the objective of increasing the net benefit to human society and preventing harm to humans and what they value; and the implementation of chosen options and the monitoring of their effectiveness. (Klinke and Renn 2004, 80).

5. Here, our thanks goes out in particular to Sönke Kreft (Team Leader International Climate Policy at Germanwatch e.V. and co-author of the Global Climate Risk Index 2014), and Matthew McKinnon (Head of Climate Vulnerability Initiative at DARA International and co-author of Climate Vulnerability Monitor 2nd Edition: A Guide to the Cold Calculus of a Hot Planet).

6. This also the basis for the distinction made by Hinkel (2011) between harm indicators and vulnerability indicators, the latter of which has a forward-looking component that can for example be based on complex, time-dependent simulation modeling of complex dynamical systems (201).

7. See: <https://drive.google.com/a/sciencespo.fr/?tab=mo#folders/0B28EIPTuGoQWWm5Lamt5OF93V1U> and <http://jcml.fr/~jacomyal/emaps-201401-viz/>.

8. Human Development Index Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 1 Apr. 2014. Web. 1 Apr. 2014. <http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Human_Development_Index&oldid=601502206>.

9. See: <http://www.highcharts.com/>.

10. After a talk with issue expert Matthew McKinnon, we expanded the list of indices on his advice.

11. This accounts not just for this subproject. The HDI is expected to be well represented in all the data sets we are studying.

12. See: <http://jiminy.medialab.sciences-po.fr/sprint_emaps_amsterdam/>. You can also download the CSV file with all the websites and their additional information such as the type of websites (e.g. NGO or Academic) and the country the websites originate.

13. See: <http://unfccc.int/national_reports/items/1408.php>.

14. See: <http://unfccc.int/essential_background/library/items/3599.php?such=j&symbol=/COM#beg>.

15. The Digital Methods Initiatives Link Ripper can be set to capture and output all internal links and/or outlinks from a given webpage. See: <https://wiki.digitalmethods.net/Dmi/ToolLinkRipper>.

16. DownThemAll is a download manager for the Firefox browser and enables the user to batch download all links, files and images contained in a webpage. See: <https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/downthemall/>.

17. The UNFCCC national communications documents can be accessed at <https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0Amv6UO8S5qbHdEp5WElsM2JDUUg3OHJCQ0czamhNRUE&usp=sharing>.

18. An extended variant of grep that supports extended regular expression syntax. This was required to meet the needs of our complicated query design (e.g. the inclusion of multiple OR operators and ignoring case-sensitivity in most of our searches).

19. In our case, we used the poppler package available in MacPorts. See: <https://www.macports.org/ports.php?by=library&substr=poppler>.

20. The overall spreadsheet of results can be accessed at <https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/16gsqBqssueHcbR5fOWIHW2ykZFU-FfoYy3Bwkb6ct5o/edit#gid=1570746579>.

21. The 2012 Human Development index rankings can be accessed at <http://www.un.ba/upload/HDR2013%20Report%20English.pdf>.

22. The 2012 ND-GAIN index rankings can be accessed at <http://index.gain.org/ranking>.

23. DARAs 2012 Climate Vulnerability Monitor in addition to data by country can be accessed at <http://daraint.org/climate-vulnerability-monitor/climate-vulnerability-monitor-2012/>.

24. See: <http://www.harzing.com/pop.htm>.

7. References

Adger, W. Neil, Saleemul Huq, Katrina Brown, Declan Conway, and Mike Hulme. Adaptation to Climate Change: Setting the Agenda for Development Policy and Research. Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research Working Paper No. 16, 2002. Print.

Adger, W. Neil. Vulnerability. Global Environmental Change 16.3 (2006): 268281. Print.

Barnett, Jon, Simon Lambert, and Ian Fry. The Hazards of Indicators: Insights From the Environmental Vulnerability Index. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98.1 (2008): 102119. Print.

Beck, Ulrich. World at Risk. 2007. Trans. Ciaran Cronin. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009. Print.

Birkmann, Jörn. Indicators and Criteria for Measuring Vulnerability: Theoretical Bases and Requirements. Measuring Vulnerability to Natural Hazards: Towards Disaster Resilient Societies. Ed. Jörn Birkmann. New Delhi: United Nations University Press, 2006. 5577. Print.

Brooks, Nick, W. Neil Adger, and P. Mick Kelly. The Determinants of Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity at the National Level and the Implications for Adaptation. Global Environmental Change 15.2 (2005): 151163. Print.

Brooks, Nick. Vulnerability, Risk and Adaptation: a Conceptual Framework. Tyndall Centre Research Working Paper No. 38, 2003. Print.

Burton, Ian, Saleemul Huq, Bo Lim, Olga Pilifosova, and Emma Lisa Schipper. From impacts assessment to adaptation priorities: the shaping of adaptation policies. Climate Policy 2 (2002): 145159. Print.

Climate Vulnerability Monitor 2nd Edition: A Guide to the Cold Calculus of a Hot Planet. DARA; Climate Vulnerable Forum, 2012. Print.

Eriksen, S.H., and P. Mick Kelly. Developing Credible Vulnerability Indicators for Climate Adaptation Policy Assessment. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 12.4 (2006): 495524. Print.

Folke, Carl, Steve Carpenter, Thomas Elmqvist, Lance Gunderson, Crawford S. Holling, Brian Walker, et al. Resilience and Sustainable Development: Building Adaptive Capacity in a World of Transformations. Scientific Background Paper on Resilience for the Process of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, 2002. Print.

Füssel, Hans-Martin. How Inequitable Is the Global Distribution of Responsibility, Capability, and Vulnerability to Climate Change: a Comprehensive Indicator-Based Assessment. Global Environmental Change 20.4 (2010): 597611. Print.

---. Vulnerability: A Generally Applicable Conceptual Framework for Climate Change Research. Global Environmental Change 17.2 (2006): 155167. Print.

Glossary of Climate Change Acronyms. UNFCCC. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, n.d. Web. 2 Apr. 2014. <http://unfccc.int/essential_background/glossary/items/3666.php>.

Hinkel, Jochen. Indicators of Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity: Towards a Clarification of the SciencePolicy Interface. Global Environmental Change 21.1 (2011): 198208. Print.

Holling, Crawford S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4 (1973): 123. Print.

Klein, Richard J.T., and Annett Möhner. The Political Dimension of Vulnerability: Implications for the Green Climate Fund. IDS Bulletin 42.3 (2011): 1522. Print.

Klein, Richard J.T. Identifying Countries That Are Particularly Vulnerable to the Adverse Effects of Climate Change: an Academic or a Political Challenge?. CCLR 3.3 (2009): 284291. Print.

---. Which Countries Are Particularly Vulnerable? Science Doesn't Have the Answer! Stockholm Environment Institute, 2010. Print.

Klinke, Andreas, and Ortwin Renn. Systemic risks: A new challenge for risk management. Spec. Issue of EMBO Reports, Science and Society 5 (2004): 4146. Print.

Kreft, Sönke, and David Eckstein. Global Climate Risk Index 2014. Germanwatch e.V., 2014. Print.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. 2005. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. Print. Clarendon Lectures in Management Studies.

McCarthy, James J., Osvaldo F. Canziani, Neil A. Leary, David J. Dokken, and Kasey S. White, eds. Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. Print.

National Research Council. Our Common Tourney: A Transition Toward Sustainability. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2000. Print.

Objectives EMAPS. Electronic Maps to Assist Public Science, n.d. Web. 2 Apr. 2014. <http://www.emapsproject.com/blog/objectives>.

Parris Thomas M., and Robert W. Kates. Characterizing and Measuring Sustainable Development. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 28 (2003): 559586. Print.

Renn, Ortwin, and Peter Graham. Risk governance: Towards an integrative approach. White Paper, No. 1. Geneva: IRGC (International Risk Governance Council), 2005. Print.

Rogers, Richard A. Coping with Vulnerability to Climate Change: Adaptation, its Limits and Post-Adaptation Mechanisms. Digital Methods Initiative Wiki. Digital Methods Initiative, 24 Mar 2014. Web. 2 Apr. 2014. <https://wiki.digitalmethods.net/Dmi/VulnerabilityClimateChange>.

Warsaw Climate Change Conference November 2013. Warsaw Climate Change Conference, nineteenth session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 19). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Warsaw, Poland. 1122 Nov. 2013. Conference.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors.

Copyright © by the contributing authors. All material on this collaboration platform is the property of the contributing authors. Ideas, requests, problems regarding Foswiki? Send feedback